"Get away from Mark," the voice on the phone said. "They're gonna kill him."

Hughes grabbed the phone.

"Who's gonna kill me?" he asked.

"Mark, you're all on the news," the caller answered.

"Yeah, Cory (Mark's brother) did an interview, and I was standing behind him," Hughes replied. "Of course I was on the news."

"No," the voice said. "They're saying you're the shooter."

"I can't explain to you all the emotions that were going through my head," Hughes says today.

Hughes, a North Texas activist, had come to the rally openly carrying an AR-15 rifle to make a point about gun rights and self-defense. That's legal in Texas. But then Micah X. Johnson, a 25-year-old loner angry over a tide of police shootings of black men nationwide, opened fire on police immediately after the rally.

Johnson had come downtown the night of July 7, 2016, to kill white police officers. Hughes, who had no involvement in the shooting, suddenly found himself an armed black man among a sea police officers who were being targeted by a sniper. Four Dallas officers and one from Dallas Area Rapid Transit would die that night.

Then, Hughes' situation grew worse.

"I have to go tell them that I didn't do this." – Mark Hughes

tweet this

At 10:52 p.m. that night, the Dallas Police Department posted a photo of Hughes on its Twitter page. In the photo, Hughes was wearing a camouflage T-shirt with his AR-15 slung over his shoulder. "This is one of our suspects," the post read. "Please help us find him!"

The streets around Hughes were flooded by streams of police headed toward where Johnson had holed up in a building at El Centro College. After getting his warning call, Hughes took off his camo shirt. He was confused. He didn't have his gun anymore. Shortly after the shooting started, Cory had persuaded his brother to give his gun to a nearby officer to prevent any misunderstanding, an incident that was caught on camera. This officer had given Mark his business card, telling him to call the next week to get his gun back.

"I have to go tell them that I didn't do this," Hughes told his friend.

"Mark, if you go over there they're gonna kill you," his friend said.

"No. If I stay here, they're gonna kill me," Hughes said. "The next police car that drives by, whether it's one officer or two, I'm gonna stop in front of them and tell them we need to talk."

Minutes after the photo was posted to DPD’s Twitter account, before anyone was able to contact Mark, Cory appeared on CBS 11 to defend his brother.

“He is not a suspect,” Cory told the reporter. “When shots started firing, I said ‘Bro, give your gun to the cop, so there’s no misidentification. Even though he gave his gun to a cop, they’ve still got him plastered all over the media like he’s a suspect.”

Around 11:10 p.m., a police officer pulled Cory away from the interview for questioning.

Meanwhile, Mark had finally mustered the courage to approach two officers. He explained how he was just exercising his Second Amendment rights and had already handed his gun to another officer. The officers brought their sergeant over to hear Mark's story. The sergeant asked Mark if he could take a ride over to the police command post to tell the officers there the same thing.

"Mr. Hughes, we're trying to do an investigation," the sergeant explained. "Can you just go over there and tell them what you just told me? It'll take five minutes."

After telling those officers his story, Mark was brought to the homicide offices at DPD headquarters.

Five minutes turned into hours — hours of interrogation, accusations and Mark telling the same story again and again.

"My skin tone is not a threat. Just as well as they have the right to carry their guns, we do too.” – Mark Hughes

tweet this

Things could have been worse for him. He could have fired his gun that day at a gun range as he wanted to do after buying accessories for his AR-15. Luckily for him, he owns and operates a snow cone business and had ice in his truck that day. If he had fired off a few shots at the gun range, the ice would have melted and his weapon would be covered in gunshot residue, giving the police one more reason to suspect him of being a shooter. For this, he considers himself lucky.

Jeff Hood, an activist and co-organizer for the rally, says he started preparing for the protest after the death of Alton Sterling, a black man who was shot by police in Louisiana that week. Days later, the fatal shooting of Philando Castile by a Minnesota police officer was live-streamed on Facebook for the world to see. This prompted Dallas activist Dominique Alexander and his group Next Generation Action Network to get involved in organizing the rally. The Castile shooting is what encouraged Hughes to open carry.

“(Philando Castile) was legally carrying. He did what he was supposed to do through his CHL (concealed handgun license) training to let the officers know that he had a gun,” Hughes says. “And that still didn’t save his life.”

Castile’s killing reminded Hughes of a recent Donald Trump rally in Dallas, where attendees were openly carrying their firearms. No one lost their lives there, Hughes says.

“I said, ‘You know what? We’re citizens. My skin tone is not a threat. Just as well as they have the right to carry their guns, we do too,’” Hughes says.

Hood says he never wanted guns at the rally. While he says what happened to Hughes was wrong, Hood believes everyone open carrying that day put the protesters’ lives in danger.

“On some level, there is never going to be a completely positive relationship between the police and citizens when a gun is in between that relationship,” Hood says.

Hood says there had been many conversations before the rally about how guns didn’t belong at the peaceful demonstrations he and others were organizing.

“I was fearful about people bringing guns,” he says. “My contacts at the police department had explicitly said, ‘Please, no guns, no firearms.’ We had been having that conversation, ‘How do we get people to not bring guns?’ because we knew if people brought guns, it put all of us in danger.”

Besides a brief conversation with his brother Cory, Mark says he had not been asked not to bring his gun.

Most depictions of the rally up until the shooting were of a peaceful demonstration. During the rally’s planning, Hood says he had been in contact with DPD to help ensure that everyone was safe.

DPD officer Shane Owens was monitoring the protest from the department’s headquarters with a few others. The night was going well, and Owens’ shift was just about over when a voice came through one of the radios.

“Shots fired, shots fired, officer down,” the voice said.

“We all just kind of looked at each other because things were going so well with no issues, and then that came on,” recalls Owens, who later left his job at the Dallas department.

What they all heard over the radio so starkly contrasted with the rest of the night that for a moment, Owens thought someone had accidentally switched the radio to a different frequency.

The voice turned out to be one of their sergeants working at the rally. From there, the team of officers was bombarded with communications coming from officers and rally attendees. There were calls regarding multiple people open carrying that night before the rally. When shots erupted, these reports increased, Owens says. Everyone with a gun was a suspect after the shooting, he says. Eventually, the team of officers began receiving calls about Hughes.

“He was in the crowd exercising his Second Amendment right.” – Simon Vincent

tweet this

“The whole reason (Mark Hughes) was homed in on was because of citizens," Owens says. "We were bombarded with calls and pleas on Facebook saying, ‘This suspect has a rifle in this area.’ It’s not like we said, ‘Fuck Hughes, we’re gonna get this guy.’ This was all citizen-driven.”

Nearly everything that could have gone wrong for Hughes that night, did. For one, Simon Vincent was working the rally.

Vincent is a freelance photographer. He uses a phone app called Stringr to find work sometimes. The app notifies him of when and where local news is taking place that publications might want photos or video of. That day, the app brought him to the march in Dallas. Among the crowd of protesters traveling along Main Street, Vincent captured the rally on his camera as the sun set. At 8:42 p.m., minutes before Johnson began shooting, Vincent snapped a photo of Hughes.

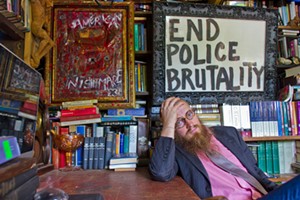

Mark Hughes was mistaken as Micah X. Johnson, the black man who killed officers on July 7, 2016.

Mark Graham

“Where’s this picture from? Do you know this guy?” the officer asked.

“It’s a crowd shot,” Vincent replied. “No. I just know he was in the crowd earlier.”

“Well, we need to get a copy of this picture, and you need to come downtown with us," the officer told him.

Before he handed the camera back to Vincent, the officer took a picture of the screen with the photo of Hughes. They got into the officer’s car and headed downtown, where Vincent says he was interrogated for hours.

“It’s funny,” Vincent says. “The officer that took me downtown, they made it sound like it was voluntary. Then, I got downtown and the whole tone changed.”

Vincent and the Hughes brothers likely crossed paths in their trips to DPD headquarters. Unfortunately for Mark, he mislaid the business card of the officer he had given his gun to, and his phone was dead, so he couldn’t contact his brother or anyone else who was with him when he surrendered his gun. That left the interrogators unable to clear him.

But Mark says the interrogators he met at DPD headquarters didn't want to hear his story. One of the first questions he was asked was, "How long have you and your brother wanted to kill police officers?" he recalls. Eventually, the interrogators were able to verify his story but said witnesses had seen him fire his gun.

"I started goin' off," Mark says. "'No one's seen me shoot my gun! Y'all know what a gun smells like when it's been shot! That gun hadn't been shot!'"

In another interrogation room, likely not too far from the Hughes brothers, Vincent says he was telling officers a different story from the one they were telling Mark. An officer walked into the room, Vincent says.

“Did you see Mark Hughes tonight?” the officer asked.

“‘Yeah, I saw him,’” Vincent told the officer. “He was in the crowd exercising his Second Amendment right.”

“Did you see anybody shoot anything?” the officer asked.

“Nope!” Vincent responded.

“Do you think this guy has done anything?” the officers asked.

“No,” Vincent said.

Vincent says the officer left the room, telling him he’d be right back.

“Literally, they didn’t come back for hours,” Vincent says.

A DPD intelligence officer familiar to the protesters finally put in a good word for him and he was allowed to leave. Vincent finally was able to check on the news of the night.

“I’m not gonna lie, I felt bad,” Vincent says. “The picture they got was my picture, but I knew the guy hadn’t done anything. But they literally grabbed my camera, took a picture of the back of my screen and said, ‘You need to come downtown with us.’ I cooperated when I probably shouldn’t have.”

Eventually, the police were able to verify Mark’s story, but he and Cory weren’t released until about 1 a.m. As they were being walked out, Mark says he angrily asked for his things back.

“I wasn’t asking in a polite way,” Mark says. “Because now, I feel like I’ve been wronged. Now, I’m demanding my stuff back. Through my demand, they put me back in handcuffs and want to lock me up for disorderly conduct.”

The same officer who pulled Cory away from his initial interview about Mark was there and let the brothers leave.

The two appeared on television for an interview at about 1:30 a.m., around the same time Micah Johnson was killed when police detonated explosives attached to a robot they had driven into offices at El Centro College.

On TV, meanwhile, Cory said he had asked the officers if they were willing to tell the public that he and his brother weren’t involved in the shooting. Police told the brothers this couldn’t happen until after their investigation.

DPD took down the Twitter post a couple of days later, but it had already been shared by thousands of people. It took Mark months to get his gun back; his camo shirt was never returned to him. Last year, Hughes filed a lawsuit accusing DPD of illegally arresting him without probable cause; illegally holding his property, his gun, car keys and camo shirt; and intentionally inflicting emotional distress upon him and his brother.

Hughes says he received death threats in the months that followed, and the incident affected his businesses.

"What they did to Mark was disgraceful, and I think the city of Dallas should have to pay over and over and over again.” – Jeff Hood

tweet this

To this day, neither the police department nor the city has openly apologized to the Hughes brothers, but Mark is looking to get more than an apology out of his lawsuit. He wants a settlement. While there have been some numbers thrown out, he says, the lawsuit is far from being resolved.

In the years following the shooting, Hughes says he was looking for answers. Why was his image released? Whose decision was it to release his photo?

"We were trying to get to the table to have these conversations," Hughes says. "We were denied, blocked, ignored. Sometimes, you’ve got to hit them where their pockets are."

Although he doesn’t agree with Hughes' decision to carry a gun that night, Hood says he thinks Hughes deserves to win his lawsuit.

“I can disagree with Mark bringing the gun that night, but what I will never agree with and never promote is what they did to Mark," Hood said. "What they did to Mark was disgraceful, and I think the city of Dallas should have to pay over and over and over again.”

If he had to, Hughes says he would do it all over again, because it was his right to carry a rifle that night. Three years later, he says the fight against inequality and police brutality hasn’t gotten any better. Anyone who wants to join the fight should get out and vote.

“Don’t minimize your voice," he says. “By thinking ‘Little old me can’t make change,’ you’ll never make the steps to make change. Find out who your local candidates are, what they stand for and understand that your voice is power.”

Hughes still has dreams about his experience, he says, but, with all the bad things that happened, some good came out of it.

“Sometimes I sit back and think ‘Damn, I was almost gone,’” he says. “But I think that more positive has come out of it than anything — larger platform, more responsibility, more leadership, more of a voice. The positive definitely outweighs the bad.”