It all started with a typo.

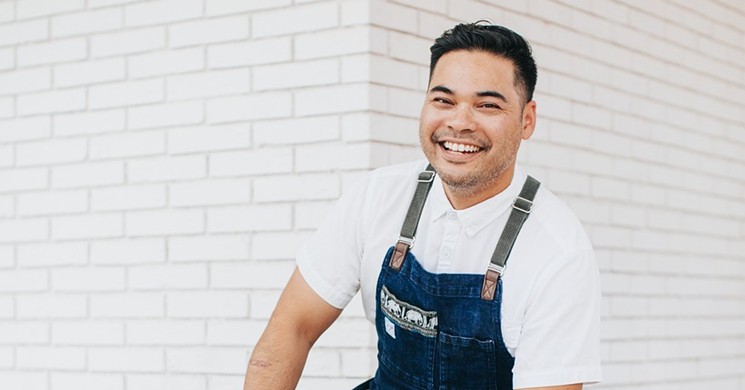

Peja Krstic, chef-owner of acclaimed Dallas Vietnamese restaurant Mot Hai Ba, reversed the h and n in “bánh mì” while writing a caption on Instagram June 16. He says autocorrect is to blame.

But then three Vietnamese American women replied to correct the typo and Krstic lashed out, sending the women a series of angry messages in public and private, accusing them of “racial profiling,” threatening legal action and calling one woman’s boyfriend.

The resulting furor has engulfed the Dallas restaurant community as Asian American food industry leaders charged Krstic with a history of personal attacks — including calling another prominent chef, Donny Sirisavath, an “Asian piece of shit,” and calling Sirisavath’s Laotian employees “bitch workers.”

Other local leaders, meanwhile, leapt to Krstic’s defense, pointing to the stress of cooking during a pandemic. Krstic himself posted an apology video calling himself “stupid” but portraying the typo incident as an isolated misstep.

Asked for additional comment, Krstic declined, adding that he is focusing on his work. This article is based on interviews with his four accusers and screenshots of public and private conversations.

This debate over one chef’s behavior ties into a national conversation about respect for non-white voices and the obligations of chefs cooking cuisines they did not grow up with.

But the conversation has also been besieged by petty squabbling, name-calling and social media debates from both sides.

Before all that, there was a spelling error.

Tiffany Tran is a macaron maker, Mot Hai Ba regular and superfan who says she was the first official customer at the restaurant’s newly opened second location. When Tran saw the typo on Mot Hai Ba’s account, she simply commented, “Bánh Mì*.” Krstic replied, “I mess it up always,” to which Tran responded, “It hurts my eyes!”

Publicly, their conversation ended there. But privately, Krstic sent Tran an increasingly hostile series of messages, culminating in a permanent ban from his restaurants and the threat of a lawsuit.

“You calling me out for a writing mistake like this is wrong on many levels,” Krstic said in his first message to Tran. “I feel very insulted and racially profiled.” He added that correcting his typo was comparable to “kicking me in the guts like I’m some piece of shit.”

“If anything everyone in Dallas knows how much unselfish I am,” Krstic continued. In later messages his emotions ran even higher: “I guess I was a complete piece of shit to you all these years. Thanks for the fake support.” In another: “Shame on you!!!!!”

“I can’t describe the feeling of being accused of racially profiling a Serbian chef because I, a Vietnamese person, corrected the spelling of a Vietnamese dish,” Tran says.

Krstic next texted her boyfriend: “Your girl took it too far with me today for no reason.” (Her boyfriend had previously worked with Krstic on several professional events.) Several days later, as Tran posted about her experience on Facebook, Krstic called her boyfriend in an effort to demand she apologize.

At that point, Tran says Krstic threatened to sue her if she continued to speak about their interaction. According to Tran, Krstic said, “I am going to make things so much worse for you.”

June 23, a week after the incident began, Krstic called Tran one last time. She says she did not answer because she was afraid he would threaten her again. But this time, Krstic wanted to apologize.

Krstic did not leave a voicemail, but he posted a lengthy, public apology video on Instagram, apologizing to “one and only person, and that is Tiffany Tran.” Partly blaming coronavirus and the stress of opening a new restaurant, Krstic said in the video that he had misread her original comments and reacted based on his misunderstanding.

But Tran is not the only Asian American who has accused Krstic of misconduct.

Chi Vu also commented on the misspelled bánh mì reference, writing, “You should spell it correctly because it is our food and deserves the respect.”

Krstic accused her of trying to “cruscify” him. Then, Vu says, another woman commented.

“Somebody told me that if I was so upset about the food then I should go back where I had come from and cook my own food,” Vu says. When she opened the notification on her phone, she was unable to view the message, because Mot Hai Ba had blocked her and was in the process of deleting all of the comments.

Vu says the woman who told her to go back from where she had come then began viewing all of her stories and liking her family photos. She made her account private afterward.

Vu says after speaking with Tran, she consulted with attorney friends and relatives to make sure Krstic could not threaten her with litigation.

“Fragile male ego isn’t something that you want to mess with in 2020,” she says.

Teresa Nguyen says she is unsure of the exact wording of her interactions with Mot Hai Ba because the restaurant blocked her on Instagram, erasing the conversation. But, shortly after her conversation with Krstic, she made her account private, fearing he would attempt to contact her further.

“Privatizing my Instagram was a wild gut instinct that probably saved me from the loads of psychological and emotional stress of having my phone number tracked down by this man,” Nguyen says. “I would not want to be contacted on my personal number with threats and demands for an apology he doesn’t deserve.”

(Note: The Teresa Nguyen who spoke to the Observer is not the same Teresa Nguyen who acts as a public relations specialist for several local restaurants. The two are not related.)

Donny Sirisavath of Khao Noodle Shop says he got into an altercation with Krstic at a bar, in which Krstic called his employees "bitch workers" and called him an "Asian piece of shit."

Kathy Tran

Sirisavath explains that the disagreement took place after a Khao Noodle Shop employee told him that someone from Mot Hai Ba had tried to offer the employee a job. When Sirisavath saw Krstic at a bar, he asked if the chef was trying to poach his employees. Krstic said no, but a debate ensued.

“I said, so you knew about it,” Sirisavath says. “Then he just went off. Threatened me, trying to fight me and we got into a shoving match. We ended outside, that’s where he called me an Asian piece of shit. Then the bartenders had to push him back inside the bar. I was pissed and a little shocked.”

Sirisavath publicized his story in an Instagram post June 24, in which he added that Krstic called Khao Noodle Shop’s employees “bitch workers.”

The post elaborated: “Apparently I have no right to do what I do. I felt like the new kid on the block, getting told I don’t deserve the respect or the recognition. He has been in the industry longer than I have, I have no right to be a Chef. I’m racist, I don’t amount to shit, I’m a piece of shit, oh I’m a Asian Piece of Shit.”

Sirisavath says other Asian Americans, including his wife, witnessed the incident. At the time, he says he “laughed it off” and focused on preparing for a trip to Laos. He apologized to the bar staff for, he says, “causing a scene.” He says he has not heard from Krstic since the altercation.

Sirisavath’s restaurant was named one of the best new restaurants in America by Bon Appetit and the chef himself received a James Beard Award nomination in his first year leading a kitchen full-time. To meet the experience requirement for a Best Chef award, the Beard Foundation counted his years working at pop-up events.

Krstic has not been nominated for a Beard Award.

The “Asian piece of shit” allegation was first raised by Reyna Duong, owner of Sandwich Hag, on her own Instagram account, a day before Sirisavath told his story.

“There is a larger conversation that needs to be had about what Dallas has collectively praised over the years, this includes the Dallas media,” Duong wrote. “I hope Peja doesn’t threaten to sue me, call me a racist, find my cell phone number to harass me, tell me my career will be ruined, or call me an ‘Asian piece of shit’ like he has with other Asian folks that have spoken up.” (She declined to comment further.)

The Dallas food community has lavished praise on Mot Hai Ba, which serves a personalized style of cuisine using traditional Vietnamese food as a loose inspiration. This March, a survey of 58 local restaurant industry insiders and writers found that Mot Hai Ba is the local food industry’s single favorite restaurant — for the second year in a row.

The battle over Krstic’s behavior has spilled over into comment sections across the internet and at least one real-life meeting, a discussion-with-drinks of cultural appropriation hosted by Whisk Crepes owner Julien Eelsen.

Some of the conversations revolve around important issues: Who gets held up as an expert in a cuisine by the media? When does temperamental behavior cross a line? How can white chefs best demonstrate their respect for the non-white cuisines they make?

Other questions, though, revolved around more gossipy issues of who insulted whom and which veiled Instagram attack was about which person.

Ultimately, there may be several lessons to learn from the “bahn mi.” The first is that, in this stressful moment, conflict can spread across the local community like fire in a drought. The discord and infighting this week quickly spiraled well beyond a straightforward discussion of prejudice and privilege.

One of several delectable courses in Saigon Block's Seven Courses of Meat feast. Saigon Block can also serve Dallasites a luxurious multicourse Vietnamese feast - cooked by Vietnamese people.

Kathy Tran

The second lesson is that, much as in the national debate on race, Dallas chefs are learning that everyone has a voice and an equal right to share their story. A chef can threaten a customer by private message, but the customer can share that message with the whole city. Likewise, white chefs cannot take for granted they will simply walk into success interpreting non-white cuisine.

“This is the person who’s speaking for us in Dallas,” Vu says of Krstic and the local Vietnamese community, pointing to the accolades Mot Hai Ba has won from diners, critics and celebrity guests such as Kanye West and Aziz Ansari. “Speaking for food that my grandparents make, and that I try to make to the point where my grandparents won’t talk shit. That’s really hard to do. It’s difficult to know that this [Mot Hai Ba] is what people think of when they think of how our food is being plated and presented.”

Vu raised a third important lesson after mentioning her own experiences as a cook in a number of Dallas-area restaurants, including Fine China, Niwa Japanese BBQ and Sprezza.

“I don’t have an issue with somebody cooking the food of another culture, as long as they do it with respect and as long as they respect people from the culture it comes from,” she says. “Respecting people enough to say, oh, I’m sorry, I spelled it wrong, let me fix it. Instead of doubling down, and tripling down, and whatever is past tripling down.”

Many chefs cook food from cultures not their own, as Krstic does, as Tran does at her business, SneakerBaby Macarons, and as Vu did when she rolled pasta at Sprezza. Cooking across cultures requires an added burden of responsibility to learn and show respect.

But even chefs who do respect a different culture must also respect the people of that culture.

“It’s not a question of whether you can cook this food, whether you’re allowed to,” Vu says. “It’s about whether you gave it the kind of respect you would give to French food or Italian food. I’m a Vietnamese immigrant who learned how to spell soppressata. You can learn how to spell bánh mì.”

Update: This article originally stated the woman who commented on Vu's post was Krstic's wife, which he says is not accurate.