In one of its current exhibitions, the institution asks, Who's Afraid of Cartoony Figuration? Curated by adjunct curator Alison M. Gingeras, who has a longstanding relationship with the Contemporary, the show (which runs through Sept. 22) explores multimedia work from contemporary artists who address critical subjects via comic-influenced drawings, sculptures and paintings.

Gingeras first became intrigued by the subject in 2002 when working on a show for the Centre Pompidou in Paris titled Dear Painter, Paint Me…Painting the figure since late Picaba. While writing an essay about figurative artist Karolina Jabłońska (featured heavily in Cartoony Figuration), she already had the concept of distilling the work of artists who use cartoony imagery to convey serious subject matter. Jabłońska's oversized canvases explore the kitchen as an allegory for what it is to be a woman, as her subjects simmer their heads in bubbhling pots or plunge their hands into frying oil.

"I felt there was a risk thinking about her work being particularly cartoony, but I knew there was substantiative content in terms of her involvement in the women's movement in Poland and her very deliberate use of this language to capture complex emotions," says Gingeras. "I started to sketch out this genealogy that went back to the immediate postwar period and the Chicago Images Movement, who were not all necessarily coming out of pop but using cartoony language to talk about weighty social-political subjects. As I started to compose it as a show, I was into touching on a diversity of generations of life, experience and issues."

The curator got busy discovering other artists whose practice she felt could lend gravitas to her concept, including queer underground icon Tabboo! (aka Stephen Tashjian), polymathic storyteller Umar Rashid (aka Frohawk Two Feathers) and ceramicist Sally Saul. Inspired by the film Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? she landed on a title that serves as a shorthand to help the viewer understand the subject matter is serious, even if the way it is being delivered is not.

"It's a tongue-in-cheek title. but I think it does just acknowledge anything that's accessible in the realms of fine art is looked at with a bit of a side eye," Gingeras says. "Whereas I think the accessibility and legibility is the great strength of this work."

The hilarious yet subversive anti-colonial paintings of Umar Rashid tell an alternate history of the American Empire via "free radical" rebels, with cholas celebrating the beatdown of soldiers, and imperialists being devoured by crocodiles. The saturated canvases of Tabboo!, a trailblazing drag performer of 1980s New York, reflect the struggles of the LBGTQ+ community for their hard-earned rights. The work of the most senior artist in the show, Sally Saul (wife of famed artist Peter Saul), conveys a sly feminism via her wacky hand-sculpted figures. Denigrated for years as a "craft" rather than a true art form, her ceramics offer a quirky take on everyday life.

Gingeras feels the gatekeepers of good taste might fear cartoony figuration because it lacks gravitas, even if the work's socio-political content merits its inclusion in art history. But more importantly, perhaps, is the idea that the fun and amusing parts of cartoony figuration allow it to appeal to a wide array of audiences, from po-faced critics to little kids or teens who perhaps are just drawn to funny imagery on display.

"I really believe in making art accessible and legible," she says. "A little kid could come in and connect with the work. Maybe a little queer kid could come in and not realize, 'Why do I like this so much?' It's not hitting you over the head with some propaganda, but there's a sensibility that allows for connections. It's almost how TikTok or those different platforms have allowed a younger generation to participate in larger social discussions. I think these paintings and sculptures are very similar because anyone can connect to them in some basic way, but if they choose to go deeper, learn more, and get into the history — that's an amazing thing."

Making History Personal

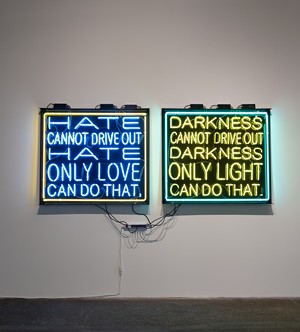

California artist Patrick Martinez uses some of the same saturated colors and social commentary as the Cartoony show in Patrick Martinez: Histories, also running at the Contemporary. Yet his iconic neon pieces, installations and large-scale multimedia paintings are incredibly personal and universally impactful.The neon-lit windows and gentrified streets of East Los Angeles have become an endlessly inspiring canvas for Martinez, who incorporates many of the aspects of the city's urban landscape into his work. Late-night drives in the first decade of the 21st century were a jumping-off point for Martinez, a former graffiti artist.

"I had a studio in downtown Los Angeles off Alameda," Martinez says. "The thing about LA at night is it's not so congested. The neon advertising is on all night in the windows; in some cases, they'd be very congested or saturated and look like a symphony of colors. One place would have a pawn shop sign or 'Pay your electric bill,' but it was always in the same format.

"My idea was to take that format and repurpose it in sending messages to speak to someone who was driving by. It wouldn't have anything to do with commerce; it was just straightforward text, and it was also like a new sculpture."

Those early works influenced the artist's pieces proclaiming, "I Don't See Any American Dream, I See An American Nightmare," or "Nothing Is Up But the Rent." When hung together, Martinez's neon pieces offer a no-duh commentary on what it means to be an American, taking the temperature of a country inflamed by rhetoric and division.

"With the work you see at the Dallas Contemporary, I'm responding to everything that's happening, whatever it might be that year, that month or that week," says the artist. "People in America compartmentalize and treat things separately, but if you take a lot of issues that deal with Americans, there are connecting intersections. Once you put these topics right next to each other, it's an intersecting point."

In addition to utilizing neon as "protest language," Martinez also exhibits work initially devised for the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco out of cinderblocks, a commentary on the continual breaking down and rebuilding of neighborhoods, as well as an homage to his late cousin. Mayan-inspired murals that blend stucco, tile, neon and three-dimensional elements offer a nod to the artist's Indigenous roots, while a series of "sheet cake" paintings honors subjects Martinez believes are left out of the history books, such as Sitting Bull.

Martinez excels at commenting on current events by breaking down an issue in a way anyone can understand. In fact, one could argue that the exhibition should be required viewing for every regional high school history or civics class until it closes on Jan. 5, 2025.

"These things [I portray] are still systemic issues, and I'm trying to record them, not like photojournalism, but record them in paint," he says. "I want to paint these things, so when a show like this happens, we can dust them off, hang them up and go, 'Who is that?' or 'What happened there?' There are certain things that can't be erased because they're in a piece of art. I'm recording things in my own way. The victor can be the writer of history, and I'm painting my own history."