Daniel Driensky and Sarah Reyes

Audio By Carbonatix

“This is a David Lowery production,” says a 7-year-old Lowery at the end of Poltergeist, his short film shot with a home camera. It starred his little brother in a sheet and showed promise even then.

Now 38, Lowery is still proud of that first cinematic attempt and posted it online. The concept hovered like a ghost in Lowery’s mind through the decades, and he reimagined it in last year’s A Ghost Story, only this time with Casey Affleck as the sheet-wearing spirit, Rooney Mara as his widow and a beauty of a score by friend and collaborator Daniel Hart.

Auteur filmmaker Lowery and musician Hart are two Dallas artists who have found acclaim together with a string of films, including 2013’s Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, in which Affleck and Mara also were not meant to be, separated in the aftermath of a crime, and the 2016 remake of Disney’s Pete’s Dragon. A Ghost Story haunted viewers with its shocking emotion, jumping through themes on the fragility of life and the universe’s mysterious timelines. The film reportedly was shot for $100,000 and has earned around $2 million.

Part of the film’s appeal was the omnipresent use of “I Get Overwhelmed,” a song composed by Hart and performed by his band, Dark Rooms, that is stretched out as the film’s main score. Hart casually showed the song to Lowery while they were working on Pete’s Dragon, and Lowery was so moved by it that he gave it a starring role in A Ghost Story, entwining it into the plot as a song connecting his characters.

“The song and the movie in my head became almost inseparable,” Lowery says. “There’s a tenderness to it that’s almost epic.”

Lowery grew up in Irving and lives in Lakewood with his wife, filmmaker Augustine Frizzell. Presently, he’s wrapping up a gig as a hired director on a few episodes of CBS’ new streaming series Strange Angel. It’s February, and Lowery’s in a sunny living room in Los Angeles’ Silverlake neighborhood. His rental home is impossible to find, even if he had been giving out the right house number. He greets Hart like a lifelong friend he hasn’t seen in ages although they’d spent time together in Utah a few weeks back.

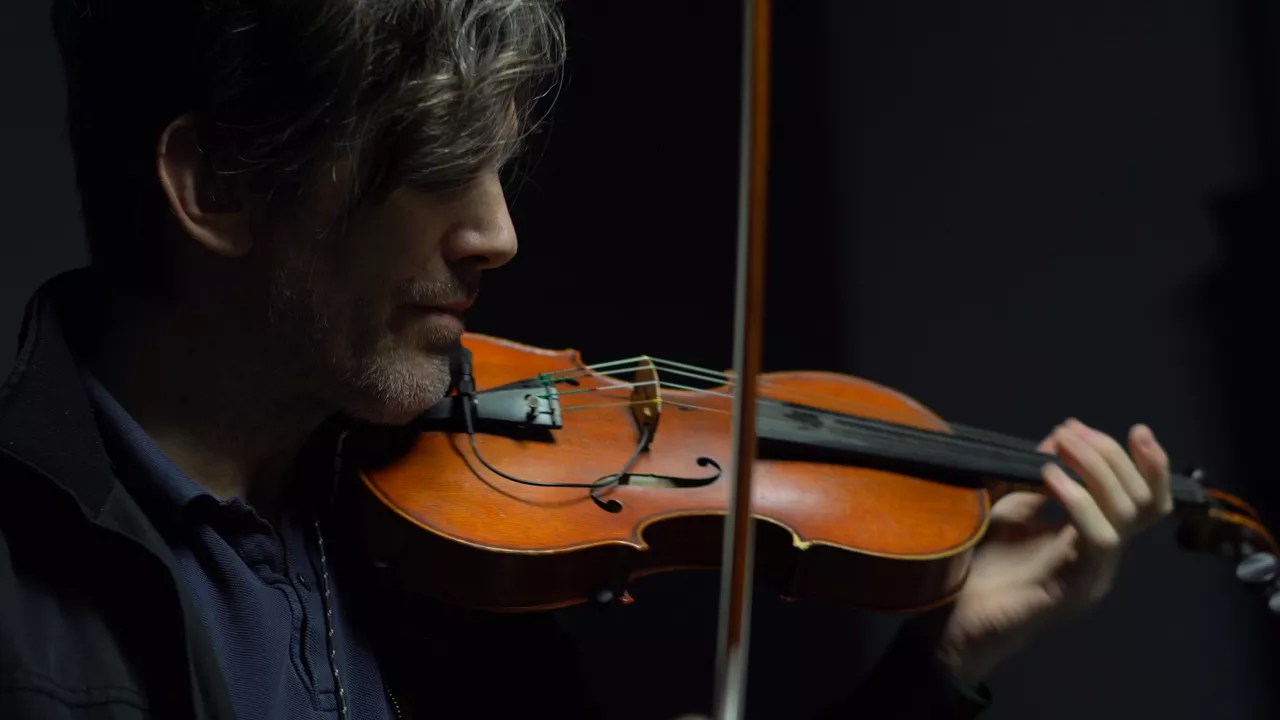

Hart’s work has brought him to Los Angeles permanently, but he’s a longtime Dallas resident and singer and violinist for Dark Rooms, a band that plays an obsessively percussive brand of R&B. He’s toured with Radiohead and David Bowie, been a member of St. Vincent and composed the score for record-setting podcast S-Town and TV shows such as The Exorcist. Together, Hart and Lowery were bound to produce work that would flummox audiences’ senses.

Much of Lowery’s work is laconic, speaking through subtlety and astonishing pictures, relying on Hart’s music to express the unspoken. While making their place in the film industry without compromising their aesthetic, they stand at the center of Dallas’ most exciting new school of filmmaking, which includes their collaborators, among them Toby Halbrooks and Frizzell.

Augustine Frizzell and Toby Halbrooks attended the Austin Film Society’s annual Texas Film Awards last month.

Maggie Boyd/Sipa USA/Newscom

The pair met through mutual friend Halbrooks, who’s Lowery’s production partner and co-writer and Hart’s former bandmate. For Lowery’s first film, St. Nick, he took Halbrook’s recommendation to hire Hart after hearing his music. The film was about two runaway children creating their own homes in abandoned houses, and Hart’s scoring, marked by the plucking on his violin strings, captured the sense of bittersweet adventure. The director and composer both describe their own and each other’s work as having a “handmade, simple quality.”

“I just went with what I knew,” Hart says, “which was recording instruments very close to the microphone with very little processing, which means that you can hear my fingers on the strings and hear me breathing.”

He and Lowery didn’t meet in person until the film premiered at the 2009 SXSW Film Festival.

“It sounded sort of how I imagined my movies looked,” Lowery says of Hart’s music. “There’s an inherent nostalgia to the sounds, and certainly a wistfulness and bittersweet quality that I responded to.”

Hart has a degree in playwriting and was a stage actor, jazz player, indie-label executive and even bus driver before Lowery steered him into filmmaking.

“I never intended to do film score,” Hart says. “I just wanted to play music in a band and tour around. So it came unexpected to me that music I was making could work for anybody’s films. But the qualities of David’s films that I respond to are somewhat intangible. I watch them, and the music comes to my head and it feels very natural.”

As Lowery wrapped up Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, producers approached him with the idea to pitch a remake of Pete’s Dragon to Disney, which ultimately selected him and Halbrooks to write the screenplay.

“They weren’t looking for edgy Sundance directors to direct Pete’s Dragon, by any means,” Lowery says. “There was a certain chain of events.”

His passion for the project prompted Disney’s eventual job offer as director, despite his lack of experience with high-budget, family films, especially one heavy with CGI effects. Lowery immediately dipped into his pool of collaborative talent, but Disney was cautious of the number of first-timers involved in the project and tried out other types of music and composers before finally agreeing to hire Hart.

“After a lot of trial and error, I said, ‘Hey, let’s try some of Daniel’s music again,’ and it fit beautifully,” Lowery says. “It took a lot of patience, especially on Daniel’s part.”

Hart canceled a tour and other projects to focus exclusively on writing half of the score without knowing whether he had the job.

“It was a very intense process,” he says.

Disney finally confirmed him as lead composer six months before the movie premiered.

“I didn’t feel pressure. Maybe there was for you,” Lowery says to Hart of the battle to get him on board. “I have the utmost confidence in my collaborators. Whenever I hire anybody for any role, I want them to have the opportunity to grow, but I won’t set them up in a position to fail. I knew Daniel was gonna knock it out of the park.”

The film starred Robert Redford and Bryce Dallas Howard and a furry dragon inspired by Lowery’s pets.

“I wanted to make a movie that’s about my cats,” he jokes.

The last few years have spurred a trend of live-action Disney remakes, including the lavish productions of Beauty and the Beast and Cinderella. Pete’s Dragon stood out with its signature Lowery treatment – its rustic simplicity with a keen eye on characters’ place in nature, so it’s as much a Lowery film as a Disney one.

“They all feel like part of the same family, even though one might be taller than the other,” Lowery says of his films’ distinct style.

Likewise, Hart finds that Disney adjusted to his sound and not the other way around.

And the doors to the Magic Kingdom remain open for the duo. Lowery and Halbrooks are in the process of writing a Peter Pan screenplay for Disney, which, if produced, would reunite the production team, including Hart as composer.

Lowery had never been to Disney World until Frizzell suggested they go for their anniversary. He found a perk in working for Disney came in the form of securing free passes. However, “the biggest perk,” Lowery says, “is you get to make a movie that millions of people around the world are gonna see.”

“I got really nice lunches,” Hart quips.

Of his initial reaction toward A Ghost Story, Hart says, “The thing I was pretty sure about was that nobody would care about this film, except us. Usually when I really love something, most people don’t care about it.”

“The medium that we’re working with can affect people immensely all over the world. It reminds me what a responsibility we have as filmmakers and storytellers and musicians to remember that.” — David Lowery

“I felt similarly,” Lowery says, but Hart relays a message he received from a newly widowed mother he met at a recent Dark Rooms show who had found the band through the movie.

“She wanted to make sure that you knew that the movie had perfectly captured the loss and the longing on both sides, is what she said,” Hart tells Lowery, who appears moved.

“The medium that we’re working with can affect people immensely all over the world,” Lowery says, “It reminds me what a responsibility we have as filmmakers and storytellers and musicians to remember that.”

In between posing for pictures, the duo laugh wholeheartedly at online videos. Off work, they get together to play laser tag or to watch Lord of the Rings marathons. Hart talks excitedly about a fantasy trip he just returned from in New Zealand, where he partook in three Lord of the Rings-themed tours with his band member and partner of 10 years, Rachel Ballard.

“Rachel decided that we need to fly some flags,” Hart says of their new L.A. home, which came with a flagpole, now displaying their allegiance to the House of Stark, the Rebel Alliance and House of Gondor.

On one of those tours, the guide announced Hart’s presence to the fellow tourists after learning what he did for a living.

“[The guide] said, ‘We have a bit of a celebrity in the vehicle, folks. This guy wrote the music for Pete’s Dragon,'” he says. “Nobody cared. They were just fine with that piece of information to have slipped them. And I feel like that’s a perfect representation of where I’m at, and I’m happy to be at.”

Lowery and Hart aren’t interested in critical praise but are grateful for their ability to select projects that speak to their interests. Hart is on his 14th film as a composer, and he and Lowery have to count aloud how many of those they’ve worked on together.

“It’s always easier on David’s films because there’s some sort of inherent understanding of what we want to do,” Hart says. He speaks of a time in a past life in which he wrote music for projects he wasn’t particularly fond of in order to make ends meet.

“I feel lucky to say that everything that I’m working on now is stuff that I’m excited about,” Hart says. “I have more work than I know what to do with.”

Today, they await the release of The Old Man and the Gun, for which Lowery dreamed up a cast that includes Redford, Sissy Spacek, Danny Glover, Tom Waits and Elizabeth Moss. Lowery says even Redford was curious as to how he wrangled such talent.

“The first thing Redford said when he got to set was, ‘Who’s your casting agent? You’ve got the best cast I’ve ever seen,'” Lowery recalls, “and I was like, ‘We literally don’t have one. These are the people that we wanted, and I sent them the script and they all said yes.’ It was a pretty lucky phenomenon.”

In an email exchange with the Observer, Redford explained why he approached Lowery with the script for Old Man, which is based on the real-life story of bank robber Forrest Tucker.

“David has a vision,” he wrote. “It almost seems personal. It has power, is full of details and it contains surprises which, from a story point of view, can keep you guessing.” He calls the partnership between Hart and Lowery one of “long-time friends, like brothers born at the hip – their relationship is one of mutual dependency and trust.”

Lowery looks back on a scene in which he directed the legendary actor as Redford rode a horse on a hill into the sunset.

“Redford has publicly said that this is his last film,” Lowery says, “and when he walked to his trailer, I said ‘You know, Bob, I think that’s the last time you’re gonna be on a horse in a movie if you stick to your retirement plans,’ and I could see him thinking about that, like, ‘That’s true; my legacy was made on top of a horse,’ in terms of movies he’s most famous for, and he just dismounted for the final time. And that’s the type of thing you file away in your memory bank as a very special moment.”

A few weeks later, Ballard spoke from her and Hart’s home in Los Angeles, which has a small studio – the place, she suggests, where Hart actually lives.

Daniel Hart has been involved in many musical projects, including his band, Dark Rooms, formed in Dallas.

Daniel Driensky and Sarah Reyes

“He’s one of the hardest-working musicians I’ve seen,” she says of her partner. “There’s always music playing in his head.”

Ballard, too, had a lifelong love of music and studied several instruments before she met Hart while working as a vendor, when he declined free ice cream from her. Ballard says she was “totally adrift in the world” and had no sense of direction around the time they met. Hart made her part of his solo backing band, which eventually morphed into Dark Rooms, where she’s now a multi-instrumentalist.

“I don’t think I would’ve played in a band if I hadn’t met Daniel,” she says. “It came about out of almost necessity.”

In A Ghost Story, Ballard is credited as a musician, actress and production assistant. She praises the way her band’s song (from the album Distraction Sickness) was used in the film.

“I think the song is just gorgeous, and it supported the emotional weight of the film,” she says.

Ballard says that although they now have millions of listeners who’ve discovered the band through the movie, this hasn’t resulted in any overnight success.

“Exposure from the film is definitely beneficial,” she says, “but I don’t have expectations that the song will make us blow up. You have to keep making more music.”

Not long ago, you could catch Dark Rooms in dark rooms at many a North Texas venue, but today they’re more likely to be found in Europe. The band is set to tour again in the fall.

“There’s a lot of respect, no yelling or arguing,” Ballard says of working with Hart. “I think we’re both very lucky to have this sort of relationship in different capacities in our lives.”

She says passersby have knocked on the door at their L.A. home, concerned about what the symbols on their flags might represent.

“We’re just nerds,” she says with a laugh much like Hart’s.

Halbrooks plays an instrumental role in the collaborations between Lowery and Hart. For starters, he brought the pair together. He and Hart met as teens living in the Lake Highlands area, and they played together in the Polyphonic Spree for four years.

“It was a traveling circus,” Halbrooks says of the group, “and Daniel Hart was always a stalwart, stoic and grounding force.” He says Hart entertained the band on the road with his virtuosic violin-playing by mimicking the sounds of practically any pop song.

In 2006, Halbrooks met Lowery when they were both doing technical film work, and they hit it off after working marathon hours on a commercial job. They caught a movie the next day, incidentally starring Affleck, their frequent future collaborator.

“We started writing a week after that,” Halbrooks says. “We both had good ideas and big ambitions.”

Halbrooks, Lowery and James M. Johnston form the production team Sailor Bear. The company just announced, in association with Tango Entertainment, the Austin Film Society and the Oak Cliff Film Festival, a grant of $30,000 to be awarded to three up-and-coming North Texas filmmakers in amounts of $10,000 each. There will also be a separate grant to cover expenses for an aspiring film critic.

“You want to pay back to the community that supported you,” Halbrooks says. “This is where we live. Let’s make it as nice a place to be as we can.”

“David has brilliant ideas,” Halbrooks says, “and I’m very tactical about matching talent with talent.”

He thought the partnership between Lowery and Hart would be a natural fit.

“Both seem relatively taciturn and have this calmness to them, but both are wildly creative,” he says.

While Halbrooks is grateful for an eventful career, which includes writing songs for his film’s soundtracks (performed by the likes of The Lumineers and Kesha), he doesn’t consider himself a Hollywood success story.

“I know we would always make our own movies, even if nobody wanted to watch them.” — Toby Halbrooks

“I’ve lived this weird, weird life,” he says. “While I do realize we’ve had some level of success, it does feel like it could fall apart at any minute. And I know we would always make our own movies, even if nobody wanted to watch them.”

Frizzell is outside of Houndstooth, her favorite spot, shielding herself from the aggressive sunshine by speaking behind large sunglasses. She’s just finished doing the festival rounds, with four screenings at Sundance and five at SXSW of her first full-length film, Never Goin’ Back, a comedy about the misadventures of two teenage girls living in Garland. Sailor Bear produced it, Frizzell appointed the music to local powerhouse Sarah Jaffe. The soundtrack includes songs by Dallas artists Topic, Zhora and Kendal Smith.

HBO just hired Frizzell to direct the pilot for the teen drama Euphoria.

“It’s the biggest job I’ve ever had, financially,” she says.

Besides husband Lowery, Frizzell’s 19-year-old daughter, Atheena, is also a writer and filmmaker. She starred in Frizzell’s short film I Was a Teenage Girl. Movies may be the family business, but Frizzell’s blood once pumped to a country-western beat. Her grandfather was Lefty Frizzell, and her musician father favored a nomadic childhood, which moved her through many Southern states and even more elementary schools.

“He wasn’t responsible,” she says of her father, and at age 15, she moved in with her brother and a friend. Frizzell trained as a vocalist for years but couldn’t overcome her stage fright, and she admits sneaking a cocktail before introducing her films to an audience.

In 2001, Frizzell, then an actress, met Lowery when he cast her in a short film. She says they dated for “one intense month,” went their separate ways for eight years and spoke again when Lowery wrote her on MySpace to say he’d had a dream about her.

“Throughout those eight years, I’d referred to him as ‘my one true love, David,'” she says, “I wasn’t longing for him that whole time; he was just this thought in my head of this person who you really care for.”

Lowery invited her to the premiere of St. Nick, which they followed with a date at Spiral Diner. He was living in L.A., and Frizzell describes the following months as a sort of mixed-decade courting, during which they texted every day but also sent letters and packages with mixtapes.

“I wasn’t sure whether it was a full-on courtship under the guise of friendship,” she says of that time, “so I didn’t know if he was feeling what I was, which was absolutely, obsessively in love with him.”

Frizzell wasn’t in the dark for long. When Lowery visited a few months later, they got engaged within two weeks. They were married the following year at a DIY, all-vegan, “winter forest”-themed wedding on the soundstage of a film studio.

Frizzell says she was “a broke single mother with a ton of help” who worked part-time waitressing and doing promotions as she home-schooled her daughter through high school. She was always a notebook-toting writer and had experience doing costume design. When Frizzell’s interest turned to directing, Lowery encouraged her to ask friends for free help. With that support, she eventually made Never Goin’ Back.

“Nothing ever made me this happy,” Frizzell says of movie-making.

Naturally, the couple compare notes on their films.

“He gives more feedback on the technical, and I on the emotional arcs,” she says.

Frizzell also has acted in several of Lowery’s films. She calls her film community family, which is partially legally accurate.

“That’s what these collaborators are. We all help each other rise together.”

Of the bond between Hart and Lowery, Frizzell says, “They’re simpatico, they have a similar outlook on life. It’s one of those instances of two people in the universe coming together where sparks fly.”

Filmmaker Augustine Frizzell is a constant collaborator with Toby Halbrooks, Daniel Hart and David Lowery, her husband.

Daniel Driensky and Sarah Reyes

Frizzell is still spinning from the whirlwind of the past few years, which took the couple to New Zealand for a year for the filming of Pete’s Dragon and now finds them both sought-after directors.

“It’s surreal,” Frizzell says. “You dream about those things, but it always seems very far. It was more surreal watching it happen to David first, even though I knew in my heart he was destined for great things. I saw the path, and when you see someone accomplish what you want to accomplish, it feels possible.”

Lowery unknowingly picks the same meeting spot as Frizzell a few days later but changes his mind when anticipating a St. Patrick’s Day crowd. Instead, he pours his heart out at Oak Cliff’s Cultivar, speaking on the common thematic threads weaved through his work.

“I realized a lot of my movies are about people who are running away from or trying to find a new home,” he says. “Steven Spielberg probably doesn’t try to make daddy-issue movies, but he keeps making them.”

Lowery is the eldest of nine. His father was a professor of moral theology, and he was raised in a creative and open-minded home, albeit in a “very strictly Catholic family.”

“While they were certainly dogmatic in their own beliefs, they encouraged their children to follow their own path and to develop their own ideas,” he says of his parents. Lowery is an atheist.

“My parents instilled in me a pretty deep sense of morality,” he says, “but there was a limit to compassion in my Catholic upbringing, especially in regards to sexuality and gender, and it’s one of the reasons I moved away from the church.”

At the moment, Lowery aims for a zenith of professional satisfaction and identifies his lack of self-confidence as his biggest hurdle to overcome.

“I have very low self-esteem, professionally,” he says. “I feel like I never am where I should be and am always striving to catch up in what the work I create could be.”

Citing Paul Thomas Anderson’s cinematic progression as an inspiration, Lowery says his favorite movie of the last decade is There Will Be Blood. He’s yet to meet the director, as Frizzell did recently. She teased him afterwards by asking, “Would you like to touch my hand now that Paul Thomas Anderson shook it?”

Lowery has voracious ambition but no hunger for fame.

“It’s great that I’m at a point now where I get to do what I love,” he says, “but in terms of the glitzy sides of this business, I have no interest in that.” He gets recognized more frequently than he anticipates.

“I would never expect to be going down the street and someone randomly knowing who I am, but it does happen,” Lowery says. “Whenever Augustine is around, she’ll make fun of me endlessly afterwards.”

As he speaks, Lowery’s tongue piercing peeks through. He got it in Deep Ellum when he was at 17. He and Frizzell also have matching tattoos, the words “I Know,” the title of a Fiona Apple song, on their hip bones. They bonded over their love of Apple in their initial exchange of music.

“I remember responding to her because she vaguely reminded me of Fiona Apple,” Lowery says.

“I was an emo kid, a heavy thinker,” Lowery says of his “very existential” burden in childhood. He remembers being somewhere around age 4 at Sunday school and causing mild alarm when he covered every biblical scene in a book completely with black marker.

Lowery says he’s relearning to appreciate the process of filmmaking. He recently developed a sense of apathy roused partly by the #MeToo movement and spurred by accusations of abuse against (among others) Oscar-winner Affleck, who stars in three of his films, including The Old Man and the Gun. On the one hand, Lowery’s excited about what a cultural shift could signify for his wife and stepdaughter.

“I think it’s a great time for them,” he says. “They’ll reap the benefits of this change.”

But, Lowery says, the movement has also affected him deeply, personally and professionally.

“It’s put me in a bind,” he says of his casting of Affleck. “The onus is on him to do something constructive. I do believe he’s a great actor and director, and I hope he can figure out a way to constructively contribute to this moment in our cultural history.

“The way in which it’s impacted me is a drop in the bucket compared to the women and men who have been legitimately victimized. It did give me pause and make me seriously consider whether I wanted to be in this industry. Getting to make films is such a privilege – to realize that so many men had taken advantage of that privilege was a terrible sadness.

“The way in which it’s impacted me is a drop in the bucket compared to the women and men who have been legitimately victimized. It did give me pause and make me seriously consider whether I wanted to be in this industry.” – Lowery

“I hope the film doesn’t suffer,” Lowery says of Old Man, “but if it does, that’s just the price we’ll have to pay as we move forward as a culture. If the film inspires conversation in that regard, I hope that it can be positive and forward-thinking and useful. And while I can’t speak for Casey, I hope as his friend that he can find an opportunity to engage and be constructive on this issue. No matter what happened, regardless of whether it’s fair or not that he’s in this position, he’s come to represent a problem, and I’d love to see him turn that problem on its head and become representative of a solution as well.”

On the recent production for CBS, Lowery made sure to balance the crew.

“There were six people above the line named David, and they were all white guys,” he says. “I said, ‘Let’s draw the line. We have enough people named David who look the same.’ You realize you need to make more of an effort,” he says.

Lowery had originally written a sex scene into A Ghost Story, but felt it might be distracting and gratuitous.

“Both the actors were relieved,” he says, “but Rooney said, ‘You know you did the same thing in Ain’t them Bodies Saints? I think you’re just a prude and don’t want to admit it.’ I love sexuality represented in movies. I just haven’t told a story that needs it yet.”

Lowery has conflicted emotions, too, on how his films are received in general, feeling a responsibility to entertain an audience while staying true to his uncommercial taste.

“As provocative and challenging as I like movies to be, I also want people to engage with them,” he says.

Despite his anxieties on set regarding his last-minute changes to scripts and other growing pains in the production process, Lowery says he maintains a “serene composure” in front of the cast and crew. He has a strict rule against hiring anybody who yells and dislikes films’ attempts to be self-consciously cool. At times, he’s instructed actors to put a rock in their shoe, figuratively and literally, to deflect their self-awareness while delivering a line. On one occasion, he attempted to shoot a happy reaction from the cast of Pete’s Dragon by either telling a fart joke or making a fart noise.

“It backfired,” he says of the tactic. “Bryce Dallas Howard made fart noises through the entire scene.”

For now, the director has no intention of leaving Dallas.

“I like that it has a degree of anonymity, as far as the perception of the outside world,” he says. “I really want to help Dallas grow in a cultural sense.”

Lowery has tried warming to cities like New York but always pines for the comfort of his hometown.

“A few years ago, I realized maybe I’ll be the person who stays, and I like that idea,” he says. “If as a filmmaker I can add a bit of cultural legitimacy to the film scene here, it would be an honor to do that. I hope that lets young filmmakers in this area realize that they can do things here.”

As Lowery heads from the patio back into the coffee shop, he finds Frizzell sitting down at a table. She is there by coincidence, each one unaware of the other’s whereabouts. He speaks of his weekend plans, which include catching an Estonian film at the theater and attending a Lorde concert. Lowery stays behind, joining his wife as she settles with her book, Girl, Interrupted.