“She was playful,” says Faye of her aunt and personal hero. “She was always telling me to do crazy things, and I was gullible enough to believe that [I should].”

One day, to shoo her away, Earnestine told her young niece that if she went outside, put a feather in her hair and jumped off the family smokehouse out back, she’d be able to fly. Faye rushed outside to pluck a feather from a black hen, climbed up to the roof and took the leap. She broke a limb when she hit the ground.

Faye’s family and vast community of locals always knew she was special. They held her to a higher standard than the other children, encouraging her to aim high. So she wanted to touch the sky. And to this day, Faye reckons that her aunt truly believed she could fly. In many ways, Faye grew up to soar far beyond the Delta.

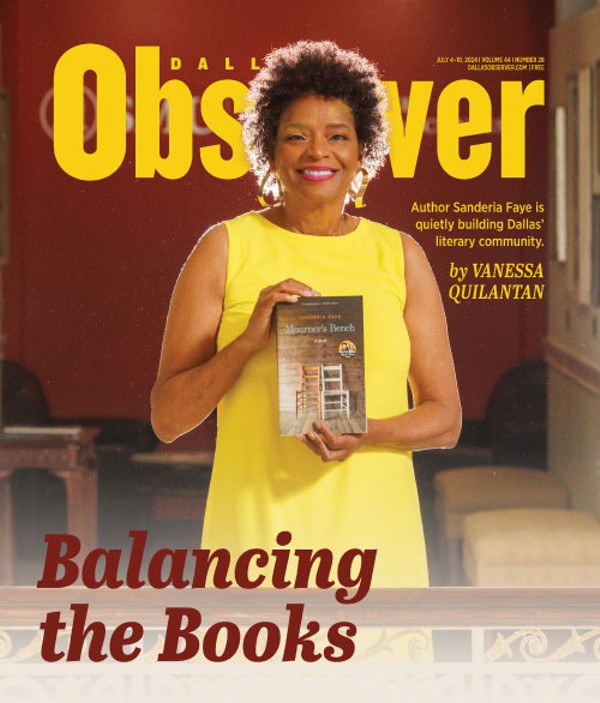

Now in middle age, Sanderia Faye is an award-winning novelist and champion community builder on the Dallas literary scene. She holds three advanced degrees (an M.F.A. from Arizona State University, another from the University of Texas at Dallas and a Ph.D. in English with an emphasis in African American literature and creative writing from Southern Methodist University).

She serves as executive director of the Dallas Literary Festival and co-chair of PEN America’s local chapter, is the founding host of the popular reading series LitNight, co-founder of the Kimbilio Center for Black Fiction and sits on the advisory board for buzzworthy nonprofit Deep Vellum Publishing.

Faye is also certified by the Court of Master Sommeliers, informing her expertise in pairing fine wines with books. She envisions one day writing from a vineyard of her own. But for now, she works from a home office to the music of Tupac and Seal from playlists she compiles to represent the themes and characters of her projects.

Though she considers herself a writer first and foremost, Faye's upbringing in a small and tight-knit town drove her passion for community building since arriving in Dallas in 2009.

“And I think that may be when I found myself,” she says, reflecting on the start of her advocacy work in Texas. “Writing and creating, that’s what felt like home to me. I was in the right place for that [when I came to Dallas]. What I didn’t know was that I would find being a professor and an executive director for the literary festival to be as equally rewarding.

“So that part is service. I say that writing is my passion, and service is my purpose.”

This purpose serves many, notes Deep Vellum founder Will Evans.

“Sanderia is a consummate literary citizen, an extraordinarily talented writer, an inspiring professor, a literary programmer who sees a need in the community and acts to fill it, an advocate to ensure the full diversity of writers and readers are connected,” Evans says. “So much of what makes literary Dallas special is thanks to Sanderia’s vision and hard work.”

An Early Love of Reading

In another effort to get her niece out of her hair from time to time, Aunt Earnestine taught Faye to read from the Bible at the age of 3, and on Saturdays, she would read it aloud to her beloved great-grandmother. After that introduction to the written word, Faye became a loner and spent most of her free time with her nose in a book, feeling like an outsider in the town of Gould.“If my parents wanted something read, they would call me to read it to them," Faye says. “Even if something was going on, I was always able to do my homework before my chores or anything like that. My education was always stressed [as important].”

After the Bible, she fell in love with Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. She saw herself in the tale’s protagonist, also a young girl coming of age in Arkansas, and that representation of her own world is something that stayed with Faye throughout her life.

After high school, she took a job in a factory, as did most of her peers who opted not to work at the nearby Arkansas state prison. But she was encouraged once again to take flight, this time by her great-grandmother.

“She said, ‘I don't think this factory thing is for you. I think you should go to that thing they call college,'” Faye recalls. “I think it was always suspected that I would do something different rather than live in the small town.”

But Faye wasn’t nudged by her family to pursue her true passion for literature. They wanted her to succeed in a more professional and lucrative field. So Faye went to school and earned a bachelor’s degree in accounting, after learning that financial auditors could travel the world for work. For many years, that’s what she did, building a successful career that eventually led her to an executive sales and marketing position in the pharmaceutical industry, and then into the corporate world via a Fortune 500 company that brought her to Dallas.

But Faye grew restless in corporate America. After finding inspiration from Oprah Winfrey’s late-’90s TV specials on the power of following one’s dreams, she eventually decided to go all-in on her literary passion, meeting with a career counselor for guidance.

“She told me that going from a business career to becoming a writer would be like turning a large ship around in the ocean,” Faye says.

She didn’t let that stop her.

“It’s not that I’ve ever set out to prove anyone wrong,” Faye says. “It’s that once I have my mind made up, I’m not just going to stop because of what someone else thinks, because they’re only seeing you from their own lens, not as you really are. No one can really tell you what you can and cannot accomplish.”

She had her mind made up to become a writer and decided to start from the ground up by balancing her business career with a return to school to earn her post-graduate humanities degrees. And that’s when she started writing.

In the academic world, she rarely found a seat at the table for aspiring Black authors like herself. But any time her self-doubt kicked in, she again found hope in Angelou’s seminal work.

“As an African American woman from the South, I had to go out and find someone like me who had done it, and done it at a high level,” Faye says. “So I would carry I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings in my book bag. And when I would feel that sense of, ‘I will never do this. I can't make it. I'm gonna quit,’ I would look at that book and I would think that she had it much more difficult than I did. And there she was, she had found [her way]."

Though she had no idea what to do with it, Faye had completed the earliest draft of her novel Mourner’s Bench by 2001. But with the 2007 housing market crash, her life was turned upside down. She was fired from her corporate middle-management job and was forced to spend time focused on her health after being diagnosed with a serious chronic illness.

Once she recovered, she spent a few years in Florida hoping to find solace by the ocean and to focus on her writing. But because she’s never been the type to sit and write without anything else to keep her busy, she took a seasonal civilian job with the Navy, where she spent eight-week excursions aboard frigates and destroyers teaching English and literature.

When she wasn’t at sea, she attended the annual "Writers in Paradise” conference at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg. That’s where her writing took off under the happenstance tutelage of Dennis Lehane, the powerhouse best-selling author of modern-day triumphs turned critically acclaimed movie adaptations such as Mystic River, Shutter Island and Gone, Baby, Gone.

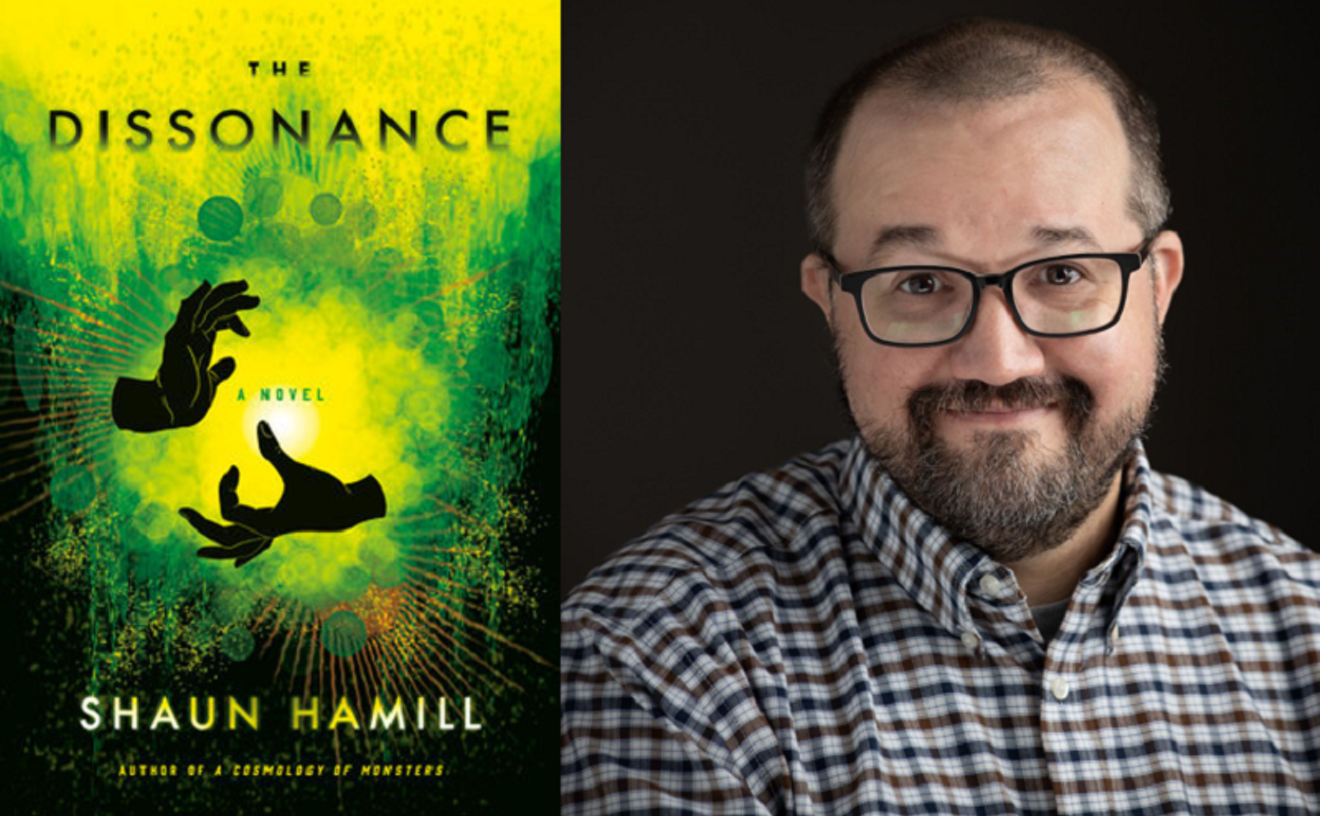

After she returned to Dallas in 2009 to finish her novel, Mourner’s Bench was published by University of Arkansas Press in 2015, adorned with a blurb from Lehane.

Mourner’s Bench is an impassioned story told through the lens of a young Black girl in 1964 facing the complex intersection of the organized civil rights movement’s arrival in her small rural Arkansas town and the highly anticipated Baptist revival in her local congregation. It’s a unique perspective addressing the largely forgotten dilemma of Black anti-integrationists in the early 1960s who feared that the growing civil rights movement was a dangerous rabble-rousing undertaking that would only make living in America worse for African Americans.

For this debut work of full-length fiction, Faye earned an Arkansas Library Association Award, a Philosophical Society of Texas Award of Merit and the prestigious Zora Neale Hurston/Richard Wright Foundation Legacy Award (which put her in the good company of world-renowned writers such as bell hooks, Junot Diaz, Colson Whitehead and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie).

Mourner’s Bench also experienced a pop-culture crossover in 2016 when it was included in “Lemonade Syllabus: A Collection of Resources Celebrating Black Womanhood,” author Candice Benbow’s viral cultural studies companion to Beyoncé’s groundbreaking combined album and experimental film Lemonade.

Shortly after, Faye began working on her second novel. It's tentatively titled Eleven, and she describes it as “how a mother and two daughters react to mass incarceration, the death penalty and corruption within a correctional facility, and how it affects their lives and the small rural community … [in] the same fictional setting as Mourner's Bench, Maeby, Arkansas, a rural town in the Arkansas Delta.” She is on track to finish this second book in just a few months, almost 10 years after the release of Mourner’s Bench.

“I allowed other things, which were important, to take precedence over my writing,” Faye says. “Like finishing my Ph.D., starting a new job [at SMU], literary community work, founding the LitNight Reading Series and reviving the Dallas Literary Festival.”

In that time, Faye has also published short-form work in The New Yorker, The New York Times and D Magazine. But the positive effect of her consistent work for Dallas authors and publishers cannot be understated.

What's the Read on Dallas?

Over the last decade or so a question has been posed ad nauseam in the Dallas arts and letters community: “Is Dallas a literary city?” In the late 2010s, cultural organizer and journalist Lauren Smart moderated discussion panels asking just that for multiple iterations of the now-defunct Dallas Festival of Ideas. The general consensus then was no, this city wasn’t reaching its full potential as a robust U.S. literary hub in the vein of New York or San Francisco. But nearly every time that question has been pondered in a public forum, Faye has been in the room. And if there’s one thing inherent in her character, it's that she is not deterred from her vision when someone tells her no.

“When you invite Sanderia to be on a panel,” Smart says, “she does the research. She shows up to panels with stacks of printed studies to prove points she wants to make, particularly about equity in the literary arts or lack thereof.”

In 2024, Dallas' literary scene has drawn global attention from The New York Times, Texas Monthly, Literary Hub, the Nobel Prize Committee in Literature and even the French government (which recently knighted Dallas’ Will Evans for his work founding Deep Vellum Publishing) has dubbed the city a burgeoning literature destination.

So when moderating a panel at Dallas Literary Festival in 2021, Sanderia Faye was asked again, “Is Dallas a literary city?” The answer was a resounding yes.

Dallas authors and community builders such as Faye, and the strides they’ve made for local literature, seem to be missing under the megawatt spotlight shining on Dallas-based publishers Deep Vellum and bookstores like Oak Cliff’s Wild Detectives. But Faye worries most about bringing awareness to local literature’s most existential threat right now: a lack of funding and resources to sustain this upward momentum for much longer.

“We don't hold the purse strings,” says Faye of the budgets Dallas literature has been able to secure, “and it can all be taken away just like that.”

Her history of service to Dallas' arts and letters includes a great deal of fundraising (empowered by her background in corporate giving), and that direct experience informs Faye’s worries about the pattern of “stops and starts” she’s witnessed throughout her work in the local literary scene. She attributes that to the city’s scarce and inconsistent access to financial resources.

“We don't have a solid foundation to build [local literature] on,” she says. “There should be a line item on the city of Dallas budget for the literary festival and other things, like the program that Will Evans wants to do that would create a place for literature in community, like a writer’s residency. He has a big idea for it. And the fact that he can't find money for it, the fact that Dallas’ literacy rates are so low … that shouldn’t be a thing, you know? We have grown by leaps and bounds, but we still need a financial foundation.”

There’s plenty of evidence to support Faye’s points. While the Dallas Office of Arts and Culture funds programs for visual arts, cultural events, music, opera, dance, theater, radio, and TV and film, it produces no literary offerings. In 2022, co-founder and executive director of local literacy nonprofit Reading to New Heights, Deidra Mayberry, told NBC5 DFW: “One in five adults in Dallas cannot read well enough to succeed at a fourth-grade reading level.”

Though a successful literary destination scene bolsters the economy and tourism revenue, a quick peek online illustrates Dallas’ noticeably low interest in that financial opportunity. On the City Hall tourism website’s sparse list of notable Dallas sights and activities, the only related recommendation is a link to the city’s main public library page. Searching the website of tourism marketing nonprofit VisitDallas also produces just one piece of content geared toward literary interests, a short list of bookstores in Dallas.

And though it’s drawing global attention (especially with the seven published English translations of Norwegian author and playwright Jon Fosse, last year’s Nobel Prize-winner in Literature), Evans’ nonprofit publishing press Deep Vellum is under financial duress, with 56.5% of total revenue attributed to contributions and a net loss of $29,001 on its 2022 balance sheet.

“There has been a flourishing of new funding programs for literary arts over the last decade, but opportunities remain to increase writers' and organizations' [access] to sustaining funding to ensure that the legacy of literary Dallas thrives for generations to come,” Evans says.

Even the Dallas Literary Festival, produced by Faye and team, went from five days of programming in 2022 to a two-day event in 2023.

For Black authors like Faye, the increased cultural awareness of Dallas’ literary community has shown very few returns in opportunity or accessibility to resources over the last decade. That’s in part why she helped found the Kimbilio Center for Black Fiction. The center programs an annual retreat, fellowships, mentorship matching and a prize for Black fiction writers. Applications are accepted every January.

Representation is a tool that chips away at barriers to entry in every part of society, just as it did when Maya Angelou drove Faye’s motivation toward the career she’s earned now. She hopes to one day see Mourner’s Bench side by side in student curriculums with To Kill a Mockingbird. The work of a Black author represented in civil rights movement education only stands to empower the Black writers of generations to come.

North Texas novelist and Faye's former classmate, Dr. Latoya Watkins, believes that Faye’s work for literary Dallas is based on a core value of inclusion.

“A lot of times you see in an industry that people create these exclusive groups,” Watkins says. “There are poets here, then the writers published by a 'big five' [publisher] or Academic Press. And then your self-published authors and spoken-word poets are somewhere off to the side, or not even really acknowledged in my experience. What Sanderia [does] is bring everyone together.”

To serve is Faye’s sense of purpose. Writing books is a massive undertaking in itself, and so is the workload of academia. With only so many hours in the day, Faye knows she cannot do her community-building work in Dallas alone, and luckily she doesn’t have to.

Authors like Ben Fountain, David Haynes, Merritt Tierce; resources like the Writer’s Garret and Write Here DFW; programs such as the Dallas Library’s new poet laureate residency; and so many more literary Dallasites are elevating the community along with Faye. And as she knows, if funding is secured, these longstanding community efforts will not have been in vain. As is her nature, she’ll put a feather in her hair and see that vision through. And Dallas will be all the better for it.