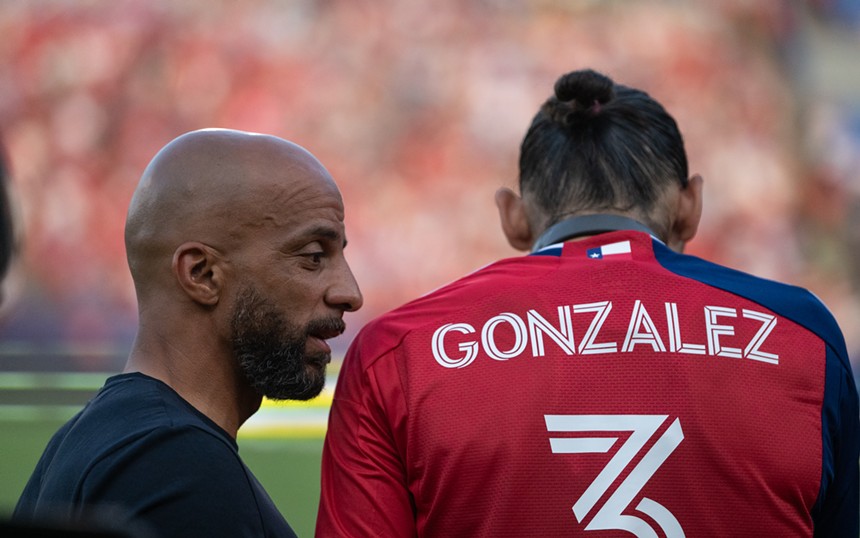

The tallest player on the field is Dallas center-back Omar Gonzalez. This is not unusual. At 6 feet 5 inches, he is one of the tallest players ever to play in a World Cup game. Gonzalez is hard to miss, especially when he starts waving and blowing kisses to the sold-out crowd.

When we asked later to whom he was directing his attention, he smiles broadly and says it’s "for his family and friends." This makes perfect sense, because Omar Gonzalez grew up just south of Interstate 30 in Oak Cliff. After more than a decade as a professional for teams in California, Toronto and Mexico, Gonzalez is back home playing for FC Dallas, and he and his extended family are loving it.

On the bench for this game is Bernard Kamungo. Physically, he won’t be mistaken for Gonzalez. Kamungo is a different kind of predator, wiry and compact. He looks fast, and he is fast. He is on the smaller side, but he has a couple of inches on Lionel Messi. Kamungo is a high-twitch athlete, and his muscles look restless even when he relaxes. His family also lives in Dallas, having moved here when he signed a pro contract before finishing high school. They moved from Abilene, but that’s hardly the story. The far more important move was the one the Kamungo family made in 2016, when they were relocated from the Nyarugusu refugee camp in western Tanzania.

As Paul Simon might say, they didn’t speak the language and they held no currency. What they did have, for the first time in Kamungo’s short life, was running water, air conditioning, enough food to eat and a bright future.

Kamungo is shy by nature. Maybe it has to do with growing up in a refugee camp, or maybe it has to do with being dropped into Abilene when your primary language is Swahili, backed up by a bit of schoolboy French.

Initially, Kamungo would sit at the back of his Abilene middle school class with no idea of what was going on or what was being said. But there were two constants that kept him grounded and hopeful: When the midday bell rang, lunch would be served, and when the bell rang at the end of the day, there would be soccer. He figured he could make this work.

And it did work. Starting on the middle school team, and then through high school, he became a star. Instructions on the field were minimal. Stay up top, get the ball, score goals. For Bernard and the entire Kamugo family, life was stable, even normal. There were steady jobs for the adults, and there was school for Bernard, with soccer during seasons and pickup games with the adult leagues on the weekends.

The shy but incorrigibly likable kid from Tanzania was starting to blossom. In an interview with the Abilene ISD he rattled off the coaches and teachers who reached out to him after he signed with FC Dallas: "Mrs. Jordan, Mrs. Garza, Mrs. Miller." The list keeps growing.

If the Bernard Kamungo story were a three-season miniseries, season one would be the hardscrabble early years in a Tanzanian refugee camp. Season two would be overcoming that background to become a high school soccer star. That would make a good story if it ended right there, but would leave out the blockbuster Hollywood conclusion to this tale. That wouldn’t be right, because in many ways Kamungo’s story is just getting started.

Omar Gonzalez would take a different path. The son of Mexican immigrants, Gonzalez is an Oak Cliff kid through and through. According to the website Behavioral Scientist, Mexican immigrants are among the fastest to assimilate into U.S. society: “In one generation’s time, we find that it becomes hard to tell apart the children of immigrants from the children of the U.S.-born. Both groups are simply American.”

In Gonzalez’s home, his parents spoke a lot of Spanish, but he would answer in English.

We may have his mother to thank for getting him interested in soccer. When the World Cup passed through the Cotton Bowl in 1994, she was a volunteer. When the call came out that kids were needed for some of the ceremonies, she signed up the whole family. By the time Brazil striker Bebeto scored twice in a quarterfinal match against the Netherlands and did his “rock the baby” celebration, 6-year-old Omar Gonzalez had made up his mind. He was going to be a soccer player.

With his focus, skill and unique size he was plucked out of high school to join the U.S. National Team’s youth program. From there it was three years at the University of Maryland, where he helped the Terrapins win an NCAA title. The personal awards rolled in as well. ACC Defensive Player of the year, first Team All-American, College Cup Defensive MVP. He was on a roll. After his junior year at Maryland, he was selected with the third pick in the MLS draft. Gonzalez was heading to Los Angeles to play with David Beckham and the L.A. Galaxy.

Back in Frisco, the team is lining up for a Wednesday match against Minnesota United. With the warm weather and three games in the span of eight days, new coach Peter Luccin is working his lineup card, trying to keep his players as fresh as possible. This night, it will be Kamungo in the starting lineup, with Gonzalez held in reserve. It turns into a wild game which FC Dallas wins, 5–3.

Kamungo has several good runs down the left side and is credited with an assist on a beautiful cross into the box that finds the foot of Croatian forward Petar Musa. Since replacing head coach Nico Estevez a couple of weeks ago, coach Luccin has asked the team to play more "vertically" — to attack the field aggressively forward to the goal box. On several occasions, the team is able to get behind Minnesota’s high-pressing back line. This style of play would seem to fit Kamungo’s skill set perfectly.

Coach Luccin grew up in the French soccer system, where he built a reputation by playing tenacious defense and not being afraid to take a yellow card. With his trim physique and shaved head, he looks like he could still do both of those things. We ask Kamungo, the moderately competent French speaker, if Luccin ever swears under his breath in his native tongue. “Not yet,” he says with a laugh, “not yet”.

In his English post-game interviews, Luccin’s constant message is that the team is good, improving, getting better. But it’s not good enough yet. It’s a message that resonates with Kamungo. He has been telling himself the same message since he signed a contract as a teenager.

Luccin was born and raised in the port city of Marseille, the third-largest city in France and one of its oldest. The historic port has for centuries attracted and blended multiple cultures — French, of course, but with a healthy mix of Greek, North African and any other people who sailed the Mediterranean.

Luccin is a soccer lifer who played for some of the biggest clubs in France early in his career, including both his hometown of Marseille and archrival Paris Saint-Germain. Then it was on to eight years in Spain. As injuries mounted and opportunities with the big European clubs dried up, he took one more shot to keep playing the game he loved. He signed with FC Dallas. His time as a player for the Dallas club was not extraordinary. Injuries were taking a toll, and his body was aging.

After spending almost two decades as a tenacious midfield defender, grabbing and fighting for every inch of turf, picking up a wallet full of yellow cards and more than a few reds, after getting knocked down and getting back up and rehabbing from injuries, Luccin was out of a job and 2,000 miles from home. He had some hard choices to make, and the choice he did make was somewhat unexpected. The hardnosed kid from Marseille would stay in Dallas and teach the finer points of the world’s game to American children.

At this point, he had a wife and kids of his own and 20 years of experience playing the game at a very high level. He just needed a new passion, and he found it in coaching.

In 2015, he changed roles within FC Dallas, moving from player to coaching the U12, U13 and U14 age groups. That experience eventually led to an assistant role with then-head coach Luchi Gonzalez, and Luccin kept the job when Nico Estévez was hired. As the 2024 season got off to a disappointing start, Estévez was let go and the rest of the season was turned over to Luccin. Before the change, the team’s play had become increasingly cautious and predictable. Scoring was down, chances were down, and the big off-season signing of Petar Musa seemed like it might be wasted money.

On the MLS television broadcasts, the word “boring” was starting to be used. Something had to change, starting with the team’s attitude, or as forward Tsiki Ntsabeleng put it after the team’s five-goal outburst against St Louis, “I just think there's a switch of mentality and attitude, the way we approach games. We start flying, and then we try to maintain the intensity throughout the game to make it difficult for the opponent. I just think that shift of mentality has made a huge difference for us.”

As for long-term results, the jury is still out. After two much-needed wins at home, the team suffered a gut-wrenching loss in Seattle, building a two-goal lead only to watch it snatched away in the final minutes. But no one walked away from that match thinking it was boring. As the team breaks for League's Cup play, Luccin's results have been encouraging. The team's troubles winning on the road continue, but in MLS play at home they are 5–1–0.

Freeing the team up to take more chances and, potentially, mistakes is a great scenario for Kamungo. One of the most remarkable aspects of Kamungo’s meteoric rise is that until he joined the Abilene middle school team, he had never played one minute of organized soccer.

We show Kamungo a picture of an adult game from the camp in Tanzania and ask him if that was really what it what like. "No," he says, "not for me."

For the kids, there was no coach, no referee, no uniforms, no boots (cleats, soccer shoes), no grass fields with goal posts and, incredibly, often not even a real soccer ball. The kids would play in the alley or any bare spot they could find and fashion makeshift balls from rags and bags, discarded gloves and condoms and anything else they could scrounge. The only things he had in common with other kids across the globe was the joy of playing the world’s game, and an idolization of the established stars he saw on infrequent TV broadcasts.

In Abilene, for the first time, Kamungo was playing in real games, on a real team, and his natural gifts were unmistakable. Like most kids in every type of sport, Kamungo would have daydreams of turning pro. Between adjusting to life in the U.S., learning English and staying current with his schoolwork, he had a lot on his plate. Texas is littered with high school hotshots with dreams of hitting it big. It just doesn’t often happen, and it probably wouldn’t have happened for Kamungo if it wasn’t for Bernard’s older brother Imani. If Bernard had doubts or was getting comfortable enough just starring on the West Texas high school team, Imani knew that there was still untapped potential in his little brother. And he had a plan. Imani was going to get Bernard a tryout with a pro club.

But with the plan came a hurdle: the cost of a tryout with a professional club. In addition to the food and the gas and the travel expenses, the price for getting in front of MLS scouts could be as high as $500. That was way too much for a family just four years removed from a refugee camp. So Imani kept looking, probing the system until he found an opening. In this case, it was an open tryout with the FC Dallas farm system, the North Texas Soccer Club — relatively inexpensive at $90, and close enough to home to get there in a single night’s drive.

Bernard Kamungo. You can't teach speed, but you can train to keep it going for 90 minutes.

Mike Brooks

Teenagers who commit to playing soccer in the U.S. inevitably need to hook into part of the “elite” club system to get the kind of training and instruction they need, and that must be paid for. Omar Gonzalez had the size, talent and commitment to get into that system, and the downstream dividends of champion-level success in college, the MLS and Liga MX. As a kid growing up in Oak Cliff, most of his immediate friends were people of color. But most of his teammates in the elite programs were white kids from more affluent families. It was, in fact, the parents of one of his new teammates who helped to subsidize his continued move up through the system.

Kamungo had neither the designer kit, the elite background nor the friends from other teams to help ease those jitters. All he had were some unique skills developed on the dusty fields of a refugee camp, enough gas money to make it back to Abilene and an older brother who had an unshakable belief in his younger sibling. Would it be enough?

It took about 15 minutes for Kamungo to realize that he could play with these other hopefuls. It took the coaches about another 15 minutes to recognize that not only could Kamungo play with them, he was better than just about all of them. For some of the young men at the event, a look from the pro league might be a measuring stick that sends them off to junior college. For others, maybe it was a vanity project all along, driven by helicopter parents who thought they could wish and pay their way into success for their children. But for Bernard and Imani and the rest of the Kamungo family, this was a life-changing, generational event. Back in Abilene, he would share the wonderful, yet somehow bittersweet, news that he was leaving his high school soccer team to become a professional.

Like Kamungo, Omar Gonzalez also never played his senior year for Skyline High School in Dallas. After 15 years training in Florida, going off to college and playing professionally across the world, Gonzalez says, "This is the first time I've lived in Dallas as an adult."

In a country that is generally starved for homegrown talent, the U.S. national team wasn’t about to let him get away. Soccer is the world’s most popular sport, and the World Cup is the world’s most-watched sporting competition. In between World Cups, tournaments such as Copa America, the Euro Cup and African Cup of Nations assemble national teams for international matches. These are some of the sport’s most prestigious titles. Legends can be created or reputations destroyed in a moment of brilliance or an instance of bad luck. With so much on the line, national soccer bodies around the world are in an intense competition to sign the best players to their nation’s team. The rules surrounding national team eligibility can become byzantine at times with dual citizenship, ancestry and parents and grandparents all in the mix.

Players are desperate to play the World Cup, and national teams are just as desperate to assemble the best talent. And while the eligibility rules can be complex, the rule that binds a player to a certain nation is not. Once you play in an international match for that country, you get "capped." “Cap” is one of those quaint English traditions from a previous century. In the U.K., if you played for God and country in an international soccer match, you received a ceremonial hat. No one gets a physical cap anymore, but once players are capped they are tied to that country for the rest of their international career. For skilled players with dual citizenship or mad skills, this can lead to hard choices. On the other hand, the various national teams want as big a pool of players as possible, which incentivizes them to bring in as many players as possible and lock them onto the team.

With his lineage, Omar Gonzalez theoretically could have played internationally with Mexico, but he got into the U.S. system early and it didn't let him go. But it’s not like they hid him from the Mexican team, as he has over 50 appearances in the U.S. colors. Looking back on his career, with all the achievement, success and occasional heartbreak, he says, "The moment I may remember the most is stepping out with the starting 11 for a 2014 World Cup match against Germany."

For Kamungo, his sudden appearance as a pro also attracted international attention, and he was invited to train and possibly appear for the Tanzanian national team in a friendly against Niger. He didn’t play that day and remained uncapped. On his return to the U.S., the national team made sure to call him up and get him into a game against Slovenia. Capped.

FC Dallas, like most other soccer clubs, is a truly international team. But these two stories are special. Omar Gonzalez is both the son of Mexican immigrants and a hometown kid. Bernard Kaumungo started life in circumstances most of us can’t even imagine. Two young Americans, and both are capped, not just in the soccer sense. This doesn’t mean that either has forgotten where they came from. Gonzalez ended up playing three seasons for Pachuca F.C. in the Mexican first division Liga MX. Located in the north of Mexico, Pachuca is a mining town and home to one of the oldest soccer clubs in Mexico. He describes the experience as "an unbelievable opportunity for him and his young family to get back to his roots." The soccer was "both skilled and passionate," and even with his broken Spanish, "the support from fans was extraordinary," he says.

Kamungo had his own getting-back-to-his-roots story during his time with the Tanzania national team. It was a side of the country he had never really seen, and a "chance to speak Swahili again." There was interest for sure, and Kamungo was torn.

In the end. it was his family who encouraged him to go all in for the U.S.

As Kamungo was training with FC Dallas, he had made a commitment to finish high school, and in 2021 he received what was really his first "cap," along with a gown and a diploma from Abilene High School. After an additional year of studying with Matt Denny, at that time the general manager of North Texas Soccer Club (and an Englishman), he passed the test for U.S. citizenship.

Between finishing high school or passing the citizenship test, Bernard acknowledges that "it was the citizenship test for sure" that was hardest. Ironically, he now probably knows more about our government structure and Abilene than most native Texans.

These teammates' stories both have twists and turns that lead to success. That makes them easy to tell, and they are stories that Americans desperately want to believe in. Anyone who reads the news knows that they are not the only "Coming to America" stories, but the idea that people from across the world can settle and, within a generation or two, transform their family's fate is a powerful reminder of the country's ethos.

Outside of our native populations, the story of every American started somewhere else. We came escaping something else, or out of desperation, or in the ugliest cases, against our will. And people still continue to try anything, risk everything to get here. It seems like most of them believe in the American dream more than those of us living it.

The good side of this is that everyone brings along their passion, and as a result we get more interesting food, music and art, and especially in Dallas, better soccer.