Music therapy is now a widely practiced form of psychological treatment. Credentialed counselors around the world use lyrics and melodies to trigger memories for people with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, help patients heal from trauma, reduce depression and improve self esteem. Sometimes patients are tasked with creating their own music, other times they’re listening to their favorite song as a way to relax. And in the middle of last year, when I found myself wondering if a leap from my apartment balcony could indeed kill me, music found a way to intervene.

To be clear, that in of itself was not music therapy. There was no therapist in the room — just me and some vinyl.

“A lot of times when I say I’m a music therapist, they say, ‘Oh I listen to music at home all the time,’” says Rebecca West, an assistant professor of music therapy at Texas Woman’s Therapy. “And music therapy is a bit more complicated than that, though I will never deny the benefits of simply listening to music.”

West has seen those benefits up close. She grew up loving Breaking Benjamin and Evanescence, but she also had a penchant for musical theater. In fact, she was moments away from declaring herself a theater major at her small liberal arts college in Indiana before a career quiz opened her eyes to another possibility.

“‘Music therapy’ was on the list of careers that might be a good option for me,” she says, “and I thought, ‘Huh, that sounds interesting.'”

Several years and degrees later, West was working at a hospital when she met a woman we’ll call Joan. Joan had recently suffered several traumatic losses in her life, including the death of a close family member. She was wracked with grief yet possessed no clear way to reconcile with all of her grief at once. Then, Joan got into a car accident.

“Sometimes we may not be able to fully process things on our own, and that’s where a music therapist comes in.” – music therapist Rebecca West

tweet this

The crash severely damaged Joan’s spine, confining her to a chair for the rest of her life. West realized that Joan was now afflicted with mountains of trauma: the loss that came with this cataclysmic crash, and the loss of her loved ones. So, West and Joan turned to music. Joan was a flautist, though West stresses you need not be a musician of any kind to practice the creation part of music therapy.

“She captured melodies for each of her family members,” says West, “including one who had passed away.”

As she recalls this years-old incident, it’s clear West is still moved by Joan’s music. This professional counselor, with her love of everything from Josh Groban to Goo Goo Dolls, has a deeply held reverence for the power of melody, but even more admiration for a melody’s impact on the mind.

“A lot of clients mention how being in music therapy allows them to be seen and heard for the very first time,” she says. “Sometimes we may not be able to fully process things on our own, and that’s where a music therapist comes in.”

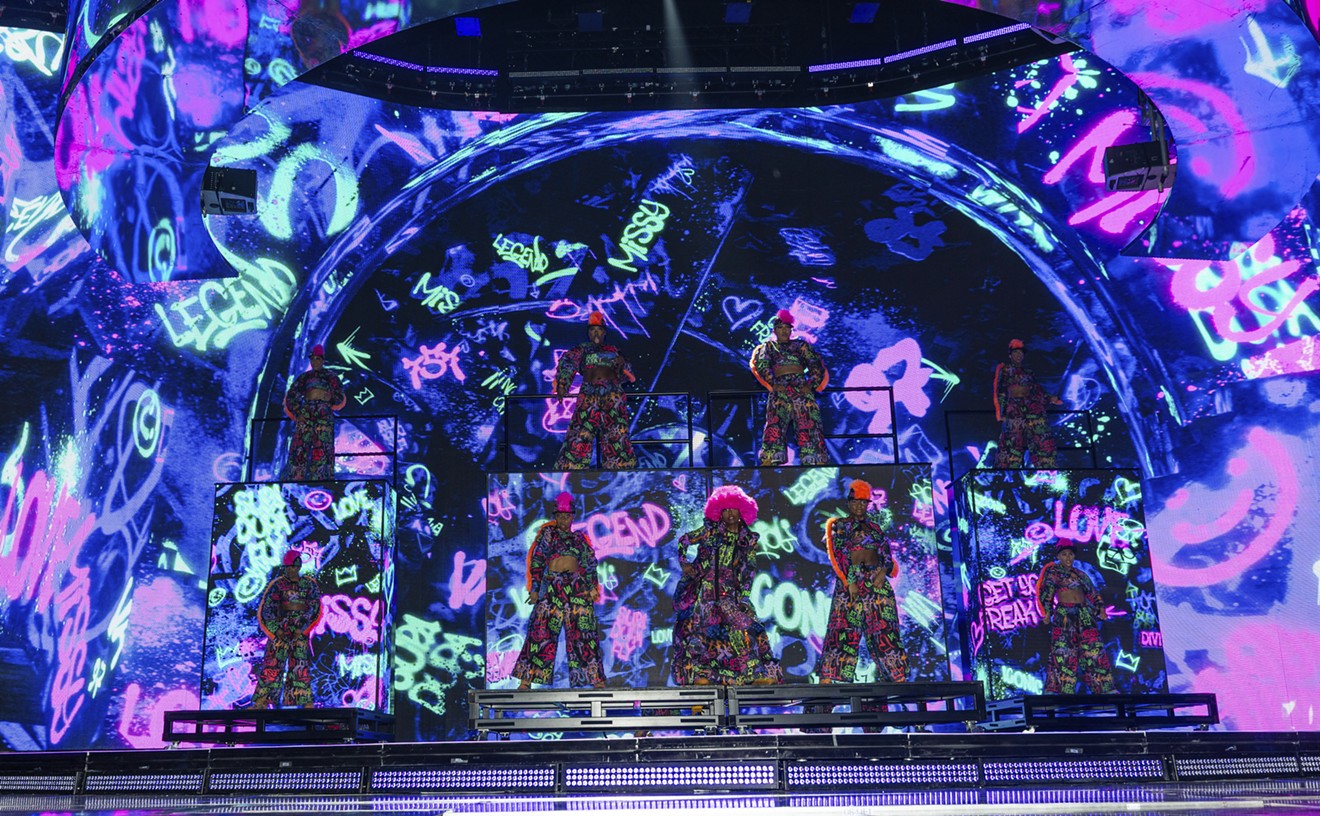

This pandemic has further ravaged the world's fragile, burdened minds, and we've lost one viable balm: concerts. A study by researchers from Imperial College London shows that concerts reduce levels of cortisol and other stress hormones. Another study, this one out of Australia, reveals that people who regularly attend musical performances have a higher feeling of wellbeing than those who don't. Those feelings of euphoric glee you get when the show reaches its zenith are actually releases of endorphins, neurotransmitters that block pain. For that same reason, some doctors play music for their patients before and after surgery.

I’ve never wanted a therapist. Be it masculine pride or a tendency to pinch every penny, I stifled each and every primal scream for help echoing inside my harried mind. Evidently, that’s how you end up wondering if a fall from 30 feet will indeed give you the fatal result you desire.

In nearly four years of writing for this newspaper, I’ve covered shows by Lizzo, Tyler, the Creator, Mistki, Marc Rebillet and Medicine Man Revival. I’ve thrashed and sweated alongside total strangers, and I’ve belted out moody lyrics next to middle-aged moms. But I never gave much thought to the chemical reaction these actions caused, or the ways those moments might save my life. But when I heard music trickling in from the apartment next door, something faint yet familiar and shamelessly sappy, I started to think.

I thought of what cheesy love songs mean to me and my wife. The laughs. The memories. The time I thought that a song that literally includes the lyric “Backstreet’s back, all right!” was performed by NSYNC. I thought about how music isn’t just the sounds emanating from that guitar or those drums or that bone flute, nor is it just the endorphins that flood your brain when your favorite song comes on. No. It’s the people that surround you when the flood rises. It’s your spouse. It’s your therapist. It’s the total strangers. I thought about all of these things, and eventually, I no longer wanted to jump.

It’s been a few months since the scene I describe above, and while the thoughts of 30-feet falls still lurk like the occasional nosy specter, I know that I don’t want to act on them. Instead, I want to play the flute.