The cherished insurgents were The Beatles, and they came to play their first and only Dallas concert at Memorial Auditorium. Dallas was the last stop of their whirlwind North American tour, and the recently dubbed City of Hate’s reputation preceded their visit.

Journalist Larry Kane was covering the North American tour on the road with The Beatles and was on the jet with them to Dallas. At one point, John Lennon nervously asked him if he had been to Dallas before. When Kane nodded, Lennon asked, “A lot of guns, huh?”

Keep in mind, their visit was less than a year after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. This, combined with the prevalence of shoot-em-up Westerns and the haywire reception they’d received at every stop of the tour so far, didn’t exactly lull them into a sense of security.

The anxiety came to a zenith hours later as the band’s limo traveled through Dealey Plaza on the way to their hotel. A spooked Lennon asked again if they were safe. This fear would set the tone for the 22 hours they would spend in Dallas.

The Dallas Police Department spared no expense in keeping The Beatles safe. Twenty-nine officers were assigned to guard their suite at the Cabana Hotel and more than 200 officers were present the night of the concert.

On the fans’ end, it would be an uphill battle to change The Beatles’ mind about Dallas being a violent, chaotic city. While some Dallas Beatlemaniacs went out of their way to extend a warm and orderly welcome, others would be the reason the band stayed holed up in their hotel room for most of their trip.

Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr reportedly remarked that the crowd was “wonderful” after the concert. But George Harrison painted a less flattering picture of the experience in his memoir, I Me Mine:

“Dallas was another madness.”

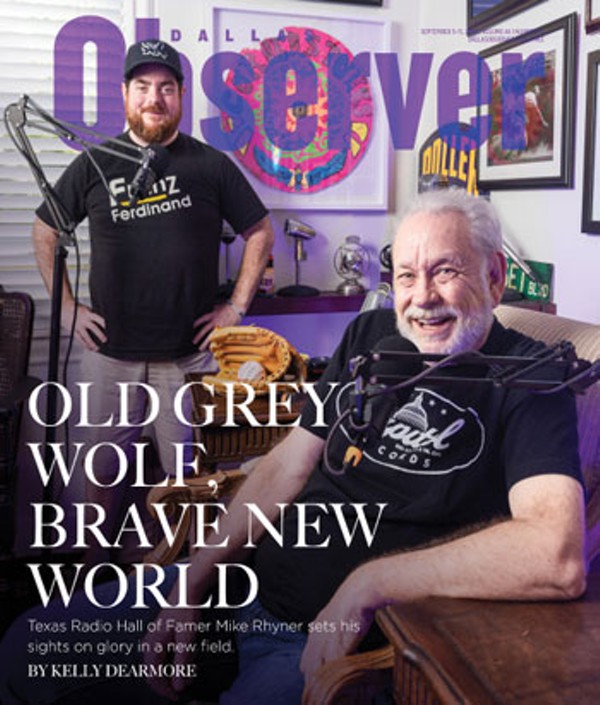

Press conference prior to the Beatles’ concert at Dallas Memorial Auditorium.

Andy Hanson/Dallas Times Herald/DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

All My Loving

By the fall of 1964, Beatlemania was crashing over America like a tsunami. The band had made its historic appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show the previous February. In August, the film A Hard Day’s Night had opened to critical and commercial acclaim. Amid the band's exhaustive victory lap, their first North American tour captivated both fans and the media at every stop.“When people find out that I’m as old as I am, and that I saw the Beatles live in Dallas, they ask me what music was like at the time,” says Danielle Wilson, who was 15 when she attended the Dallas show. “It was pretty stuffy. I was a little bit too young for Elvis, and I certainly didn’t like Frank Sinatra or any of those old crooners, because that was just not with it. But when The Beatles came along, it’s like they blew music wide open.”

Dallas fans had been following the tour every stop of the way, and some used the time to mobilize the troops.

Elaine McAfee Bender was 14 and living in Fort Worth in 1964. She had known about The Beatles from the radio and magazines, but like millions of people, she was awestruck by their Ed Sullivan appearance.

“I was just completely blown away,” she says. “I loved the songs. I loved the look. I liked the long hair. Of course, my grandmother and my mother were very critical of long hair.”

After finding manager Brian Epstein’s information in a magazine, Bender wrote to him asking for permission to start an official fan club. Epstein obliged, and the North Texas Beatles Fan Club was born.

“We were ahead of the whole American fan club operation,” Bender says with pride. “That was after us. And they allowed us to stay with the English administration, and I got to be friends with a lot of people there. At some point, they asked me to register with the American fan club, which I did, and I would get instructions from England and from America.”

Meanwhile, two focused and dedicated 15-year-olds were making moves of their own in Dallas.

“Stephanie Pinter and I were good friends, and we were both very much enamored with their music,” Yolanda Hernandez says. “We kind of went Beatle crazy when they came on the scene.”

Pinter, who could not be reached for this story, recounted her version of events in a letter to writer and collector Mark Naboshek in 1991.

“The Beatles were in our lives to stay,” she wrote. “We would discuss which Beatle we liked the most, which Beatle had the cutest personality and all the other cliches I’m sure you have read numerous times.”

Pinter’s mother was the one who suggested they start a fan club, having just read about the formation of the American club in the news. Hernandez wrote to the club’s headquarters in New York requesting chapter membership; weeks later, it was granted. The girls were now co-presidents of The Beatles Fan Club USA, Chapter 24. They would go on to wear matching outfits to all Beatles-related events to distinguish themselves as co-presidents.

Tickets for the Dallas concert cost $5.50 and went on sale on June 1. Fans camped out overnight to ensure they’d get a spot. Bender was among the fans who skipped school to wait in line.

“I wasn't the type to just skip school, but I was wanting to get tickets, so I paid a neighbor, a friend of my brother’s, who was actually 16 and had a driver's license [to take me],” she says. “As responsible of a young lady as I was, I was just not going to miss The Beatles.”

A report from NBC5 from the time compared the line to an “open-air slumber party,” with the teenage campers bringing snacks, blankets and magazines to help them pass the time. In subsequent years, it became more common for fans to wait like this for highly anticipated concerts, movies or other major cultural events, but it was still considered extreme in 1964.

“Never have so many waited so long for so little,” NBC5 reported. Grownups just didn’t understand.

Carol Barnes, a 13-year-old classmate of Bender’s, had never been to a concert before and desperately wanted to see The Beatles. She thought she had missed her chance when the tickets sold out within a day, but her luck changed when a pair of spare tickets went up for sale over the radio.

“I really, really lucked out,” Barnes says. “A DJ came on the radio and said somebody had some tickets to sell. [...] I called up and got the phone number, and we went and picked up the tickets.”

Barnes’ lucky streak continued when she realized her seats would be in the third row.

”I don't know how they got those third-row tickets,” she says. “I would have thought somebody would sit in the line all night, or have to know somebody to get those third-row tickets.”

No radio station was named an official sponsor of the Dallas show, but KLIF put in the work to be associated with it. The station sold branded memorabilia ahead of the show, correctly assuming it would all show up in photos of the concert. One pennant read “Beatles, we love you” on the front and “But our heart belongs to KLIF” on the back.

The station's big-ticket item was a “KLIF Beatle Brigade” sweatshirt. Barnes persuaded her parents to drive her from Fort Worth to Dallas to get one so she could wear it to the concert. She lost the sweatshirt decades ago, but she still lovingly describes it as though it were sitting in front of her.

“It was real neat,” she says and sighs. “The picture of them on the front was from the ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ single. And that’s what I wore.”

When Hernandez and Pinter heard The Beatles were coming to Dallas, they became women on a mission, and their plan involved more than just attending the concert. Using their official fan club stationary, they penned a letter to Epstein asking for a chance to meet the band and present them with gifts on behalf of the Dallas fan club. They were shocked and elated when Epstein wrote back saying that it could be arranged.

“The letter did not say how, when or where,” Pinter wrote. “But it was enough to know that Brian Epstein had actually read our letter and responded.”

Dallasites wait outside the Beatles press conference for a glimpse of the band.

Andy Hanson/Dallas Times Herald/DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

A Hard Day’s Night

The band’s jet sent shockwaves through the crowd of fans as soon as the wheels hit the ground. When the doors opened and the Fab Four emerged, they were given a warm, Texas welcome in the form of hysterical screaming. This had been the soundtrack of their entire tour, and Dallas was shaping up to be the grand finale.

“I remember very clearly all of them and their entourage coming off down those steps,” Bender says. “And we're waving and going, ‘Welcome! We love you!’”

WFAA footage from the landing shows around 2,000 fans sobbing, pressing up against the fence and waving around merch and magazines. Some look on the verge of fainting.

Bender says the Dallas arrival was actually quite tame, especially compared with a riot she saw break out when the band landed at the Houston airport less than a year later.

“I didn’t see anyone try to climb the fence,” she says.

The mop-topped heartthrobs were given dapper, 10-gallon white hats by the Dallas Civic Opera upon their arrival. The hats were noticeably too small for their heads, but they still flaunted them on their walk from the plane to the limo.

After the band’s limo left, fans scrambled to race them to the Cabana Hotel, off Stemmons Freeway. At the time, it was a striking and fairly new piece of midcentury architecture owned by Doris Day. In the years to come, it would play host to many a celebrity, including Jimi Hendrix and this other counterculture icon named Richard Nixon. The building was later used as a prison and is now being converted into an affordable housing complex.

But it was this night that the hotel truly earned its reputation as a historic site, as 1,800 Dallas Beatlemaniacs were waiting for the band as they arrived. The limo pulled around to the back entrance to avoid the crowd, but the crowd outflanked the vehicle and surrounded it on all sides.

The Beatles had to make a mad dash through the throng, which was hellbent on lovingly tearing them to pieces, grabbing at their clothes, jewelry and glasses in hopes of nabbing a souvenir. Both George Harrison and Ringo Starr lost their footing at one point and had to be picked up by officers to avoid being trampled.

Bender and her friends were among the fans outside at the front of the Cabana, straining to catch a glimpse of The Beatles. The crowd quickly reached an unsettling density and had begun jostling each other to get closer to the windows, with the kids at the front tightly pressed up against the glass.

“We were getting kind of packed in, and at some point I just said, ‘We’ve gotta get out of this. This is potential danger,’” she says. “So we kind of pulled back and stayed in the parking lot.”

Bender’s intuition turned out to be on point.

“I heard the sound of breaking glass,” she says. “I heard screaming, and not happy screaming, but panic and people dispersing. And I heard an ambulance coming.”

The pressure from the crowd had caused the glass to break. Several fans had fallen through the window and had to be hospitalized for severe cuts and lacerations. Others were injured by falling glass and treated on site by paramedics.

The Beatles would later postpone some of their Dallas engagements to call and check in on injured fans.

Bender was safe in the parking lot when the window broke, but she did have to tend to a personal crisis once the media arrived in the morning.

“News channels were there with cameras in our faces and everything,” she says. “I was like, ‘Can you please not tell our parents that we're here? And will you please not tell our teachers why we skipped school today?’”

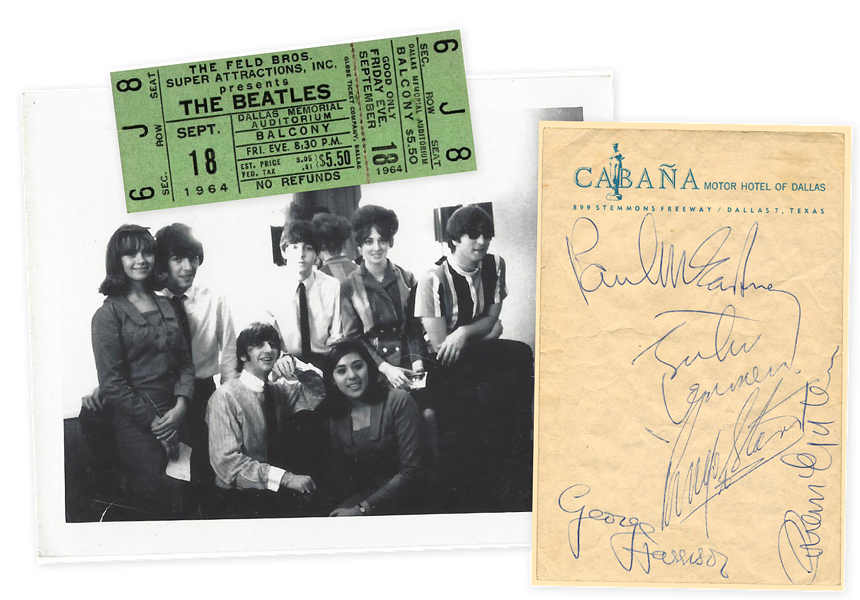

A polaroid of the Beatles Fan Club meeting the band in Dallas; a ticket stub from the show; Beatles’ autographs on hotel note paper from the night.

Courtesy the Mark Naboshek Collection

Boys

While other fans were clamoring outside, Pinter and Hernandez were being smuggled up to the band’s suite in a laundry basket. They had with them an oversized cigarette lighter with an engraved message: “To the Fab Four – Jolly John, Pretty Paul, Gorgeous George and Ring-a-Ding Ringo – Dallas Fan Club #24.”Thanks to Epstein's cooperation, the fan club parliamentarians were able to make arrangements with the hotel ahead of time and had earned their coveted meeting on a promise to stay calm and mild-mannered. They took their roles as fan ambassadors incredibly seriously. In her letter, Pinter refers to herself and Hernandez as a dynamic duo, the Lennon and McCartney of decorum and professionalism.

“Our main goal was to be a different kind of Beatles fan,” Hernandez says. “To behave well. To enjoy the concert, enjoy ourselves, but not go absolutely physically crazy to where we might embarrass our family or ourselves or whatever.”

As the co-presidents were escorted to The Beatles’ suite, their goal to remain model fans weighed on them. As principled as they were, they were still 15-year-old girls whose world revolved around the men they were about to meet.

“We showed our appreciation with polite responses and no screaming or fainting,” Pinter wrote. “All the while, we were screaming inside.”

“They took us through some double doors, and there they were,” Hernandez says. “They were as gracious and as gentlemanly as they could possibly be. Just very normal people in normal, casual clothes.”

The girls had countless questions for The Beatles, but were surprised when their idols had just as many questions for them. They wanted to know everything about Texas, a place that fascinated and frightened them.

“They were asking us what it looked like outside,” Hernandez says. “They envisioned Texas to have a prairie and cactus and horses. And we were like, ‘No, there's a freeway out there. There are cars. There are a lot of people that would love to get to you.’ We were trying to explain to them that that was the Old West.”

“George asked me all about Dallas,” Pinter wrote. “We talked about the tour and the different cities and how big the United States is.”

The girls presented the lighter to the band and mentioned that they also had four black Stetson hats for them. They had intentionally left these gifts at home in hopes of using them as leverage to get a second meeting.

It worked.

The mention of black hats immediately piqued the band’s interest, as they apparently felt the white ones they’d received at the airport (which they still had with them in the suite) didn’t suit them. Lennon had previously thrown his across the room in distaste.

“You have black hats?” McCartney asked.

Of course they did. They had read in a teen magazine that black was the band’s favorite color.

Lennon was quiet for most of the meeting, according to Pinter, but he did have a lot of questions about the Kennedy assassination. It had been weighing on him the entire trip, after all.

“He was intrigued by the fact that I had seen President Kennedy only 17 minutes before he was shot,” she wrote. “Paul even came over to where we were when I was explaining the events that transpired.”

Pinter went on to write that this conversation would come back to haunt her after Lennon himself was shot and killed in 1980.

At one point, they heard the window break and screams from fans downstairs. It was apparently Lennon, who had been sitting by the window and was startled by the noise, who suggested they check in on the injured fans.

Epstein reminded Pinter to collect the band’s autographs, which she did using a piece of hotel stationary. Pinter insisted Epstein sign as well, a request he resisted before obliging. At that moment, he was her favorite Beatle for helping her and Hernandez arrange the meeting.

Before their meeting concluded at around 3 a.m., Starr suggested that their press officer take a photo of everyone with his Polaroid camera. Pinter wanted to stand next to McCartney for the picture, but those plans fell through when Harrison pulled her close to him.

In between photos, Harrison asked Pinter and Hernandez how old they were. When they said they were 15, Harrison laughed.

“Brian, we have illegals in the room!” he joked to Epstein.

Lennon then offered them tickets to the show as well as passes to the press conference.

“We mistakenly said we already had [tickets],” Hernandez laments. It was true, of course, but their seats were up in the balcony. “God knows how good his tickets would have been versus ours.”

They did accept the press passes and as they were leaving, both McCartney and Harrison reminded them about the black hats. Pinter and Hernandez promised to bring them to the press conference.

After leaving the suite, Pinter and Hernandez made their way back to the service elevator and as the doors shut, they dropped the facade.

“We held on to each other and then came the release,” Pinter wrote. “The tears and hysterics of two fans.”

The Beatles answer questions at the Dallas press conference in 1964.

Andy Hanson/Dallas Times Herald/DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

Things We Said Today

WFAA’s Bert Shipp was the only Dallas reporter to score a one-on-one interview with The Beatles, which he did by promising the officer stationed outside of their dressing room an autograph for his daughter.

In the ambush interview, McCartney is wearing a black Stetson, one of four that had just been given to the band by Pinter and Hernandez, and it appears to inform the tone of the interview. The band answers some of Shipp’s questions in exaggerated Texas accents and McCartney spends much of the interview pretending he’s riding a horse.

Shipp informs McCartney that in Westerns, black hats are normally worn by the bad guys.

“I’m going to be the good bad guy,” McCartney responds. “How’s that?”

Shipp’s questions are met with tongue-in-cheek, sarcastic responses that had become the band’s trademark.

“Do you have any political affiliations at all?” Shipp asks Starr.

“No,” Starr answers dryly.

“He doesn’t even smoke,” Lennon adds.

“I don’t even smoke,” Starr confirms before taking a drag of his cigarette.

When asked by Shipp what kind of girl they prefer, Lennon and Harrison have the same answer.

“My wife,” says Lennon, who had been married to Cynthia Powell Lennon for two years at that point.

“John’s wife,” Harrison jokes. Lennon punches his arm.

The antics continued at the press conference, where dozens of reporters crammed into a small room in Memorial Auditorium’s basement to ask them about their clothes, whether they liked America, when they were coming back and what they liked about Dallas the most.

“The organization,” Lennon sarcastically responded to the last question.

“It was very hectic,” Harrison added.

When asked about Ringo for President, a publicity stunt meant to coincide with the upcoming election, Starr made a joke about the Kennedy assassination.

“You better watch yourself down here,” he told the reporter. The response was a mix of gasps and laughter.

Fifteen-year-old Donna Canada covered the press conference for Datebook, a popular teen magazine at the time. She was the youngest reporter present.

“I was very nervous since I had never been to anything this exciting in my whole life,” she wrote. “The policeman who let me in was a little hesitant, as all the kids outside the door chanted, ‘That’s not fair! She’s a teenager.’”

Canada, who could not be reached for an interview, delivered on what Datebook readers were likely interested in with a detailed account of what The Beatles wore.

“Their attire could be described by any American girl who was familiar at all with the Beatles as nippy, gear or the fabmost,” she wrote, using the British slang popular among American fans at the time. “It truly was.”

Canada didn’t have a tape recorder and had to frantically scribble down the questions and answers in her notebook. Her transcript is impressively accurate, considering she was taking additional notes as well.

“Paul smiled constantly,” she wrote. “John, I feel, was the wittiest. He spoke up the most, too [...] Ringo was my favorite when I arrived, but as I left the conference, was last in line. Once I tapped him on the shoulder and he didn’t even turn around. He seemed so bored with the whole thing.”

Canada also had a silent but humorous back-and-forth with Harrison.

“George stared at me,” she wrote. “After about five minutes, he winked. I looked around and there was no one behind me, so I winked back. He surprised me greatly by winking again. I felt like running up to him and hugging him, but I couldn’t risk being thrown out, so I stuck to my first impulse and winked again. I’ll never forget it.”

As the conference concluded and the concert was about to begin, McCartney invited Canada to the band’s dressing room to get their autographs.

“I declined his offer because I didn’t want to be the only one in there,” she wrote. “I am crazy, now that I think of it. But I really got to meet and speak with the Beatles. It was a dream come true.”

Twist and Shout

Wilson doesn’t remember what songs The Beatles sang in Dallas. The Frank Sinatra detractor mentioned earlier in this story doesn’t even remember how she got her ticket. (Details like that get fuzzy after 60 years.) She mostly remembers what she was wearing and who she wore it for.“All I remember is screaming and probably crying,” Wilson says. “I can remember standing there in my blue Ivy League-style shirt, reaching my arms out and screaming, ‘Paul!’”

In fairness to Wilson, very few who attended The Beatles’ Dallas concert can remember what songs they performed because they couldn’t hear them to begin with. The screams of 10,000 fans easily overpowered the primitive PA system at Memorial Auditorium.

The predominantly teenage crowd was wound up tight and ready to explode after sitting through four openers. The Bill Black Combo, The Exciters, Clarence “Frogman” Henry and Jackie DeShannon were formidable performers but barely stood a chance against the antsy fans.

“Instead of just like one big main artist, it was more like a variety type thing where they would have a show with a bunch of different acts,” Barnes says. “The other acts were good, but everybody just kept saying, ‘No, we want The Beatles.’ So nobody paid much attention to them.”

KLIF’s Ron Chapman and Dan McCurdy were bestowed the honor of announcing the main event after flipping a coin with other local DJs. They barely made it through the group’s name before deafening screams and cheers drowned out both their voices and the opening chords of “Twist and Shout.”

“The place went crazy, of course, with screaming and people trying to rush the stage,” Bender says. “And not just girls. There were some guys in there too.”

“You couldn't hear a damn thing,” Hernandez says. “There were so many people screaming. There we were in the first balcony just going, ‘Shut up!’ [...] and trying to get people to just be quiet so we could hear them play.”

Barnes fared better, but not by much.

“Ringo played the drum so loud you can hear it over everything,” Barnes says. “They couldn’t drown him out."

Bender, whose seat was closer to the stage, says she could hear them fine.

“I could hear the harmonies. I could watch Ringo keeping the beat,” she says. “I don’t know how they stayed together so well, but they sounded good. They were skilled at what they did in those situations with a lot of screaming. I never picked up on anything being off.”

At one point, fans in front of Bender stood up on their chairs. She reluctantly followed suit so she could see McCartney sing “All My Loving.” He apparently made it worth her while.

“I swear he looked right at me and winked,” Bender says.

Wilson, who was in the balcony to the left of the stage, also felt a connection with McCartney at one point.

“I was absolutely convinced at the time that Paul saw me in the audience,” she says. “I wrote a letter to him to say that I was the one in the balcony in the front row with my blue shirt on.”

The Fab Four played 12 songs — “Twist and Shout,” “You Can’t Do That,” “All My Loving,” “She Loves You,” “Things We Said Today,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “If I Fell,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “Boys,” “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Long Tall Sally,” in that order. It added up to only about 30 minutes.

“It was disappointing that it was over so fast,” Barnes says. “I don't remember too much after the show, but my parents dropped us off, and they had to go wait for us to get out of the show before they picked us up again. They said they got out to a back street to wait after the show and saw The Beatles drive by.”

“I didn't go back to the Cabana,” Bender says. “I knew that I was already in trouble with my parents, so I went back home and so did my friends. We were all just happy to be there.”

Wilson, who was not at the Cabana before, did pay the hotel a visit after the band left.

“We had paid a housemaid 50 cents to let us into the Beatles room before it got cleaned up,” she says. “And I remember very distinctly that we were in absolute awe at the thought that we were standing in the room that The Beatles had been in. [...] I remember we went into the bathroom and touched the toilet seat saying, ‘Oh, they sat on this toilet seat!’”

She trails off laughing.

“She probably took us into any empty hotel room that hadn’t been cleaned up yet,” she admits. “But we believed that The Beatles had been there.”

After the show, The Beatles flew to a Missouri ranch owned by Fort Worth businessman Reed Pigman, who also owned the jet they had traveled on the whole tour, for a much-needed day off. In addition to resting and recuperating, they rode horses and had a real-life cowboy experience that was probably far preferable to horsing around in the Memorial’s basement.

And to complete this Western fantasy, the entire time they wore the black Stetsons they received in Dallas.