Hip-hop has always been about struggle. The struggle of the streets, the struggle of the hustle, the struggle of being young and black in America. In 2015, after years of turmoil, those struggles reached a tipping point, exploding into the national consciousness because of an ever-increasing body count. A cop in South Carolina gunned down an unarmed black man. Chicago police paid off the family of another unarmed man, shot 16 times, many of those shots fired while he was down on the ground. In North Texas, a white McKinney police officer showed up to a pool party, waving his gun at unarmed black teenagers and violently pinning one young girl to the ground.

The Dallas hip-hop scene, which has long had a reputation for producing party music, underwent what felt like a coming of age in 2015. Dallas may have brought us the D.O.C. and Erykah Badu over the years, but Vanilla Ice is still its best-known and best-selling rapper. Viral novelties like “The Stanky Legg” and “Do the Ricky Bobby” only reinforced the city’s reputation. But in a violent, rage-filled year, the Dallas hip-hop community responded with some of the year’s most important local music.

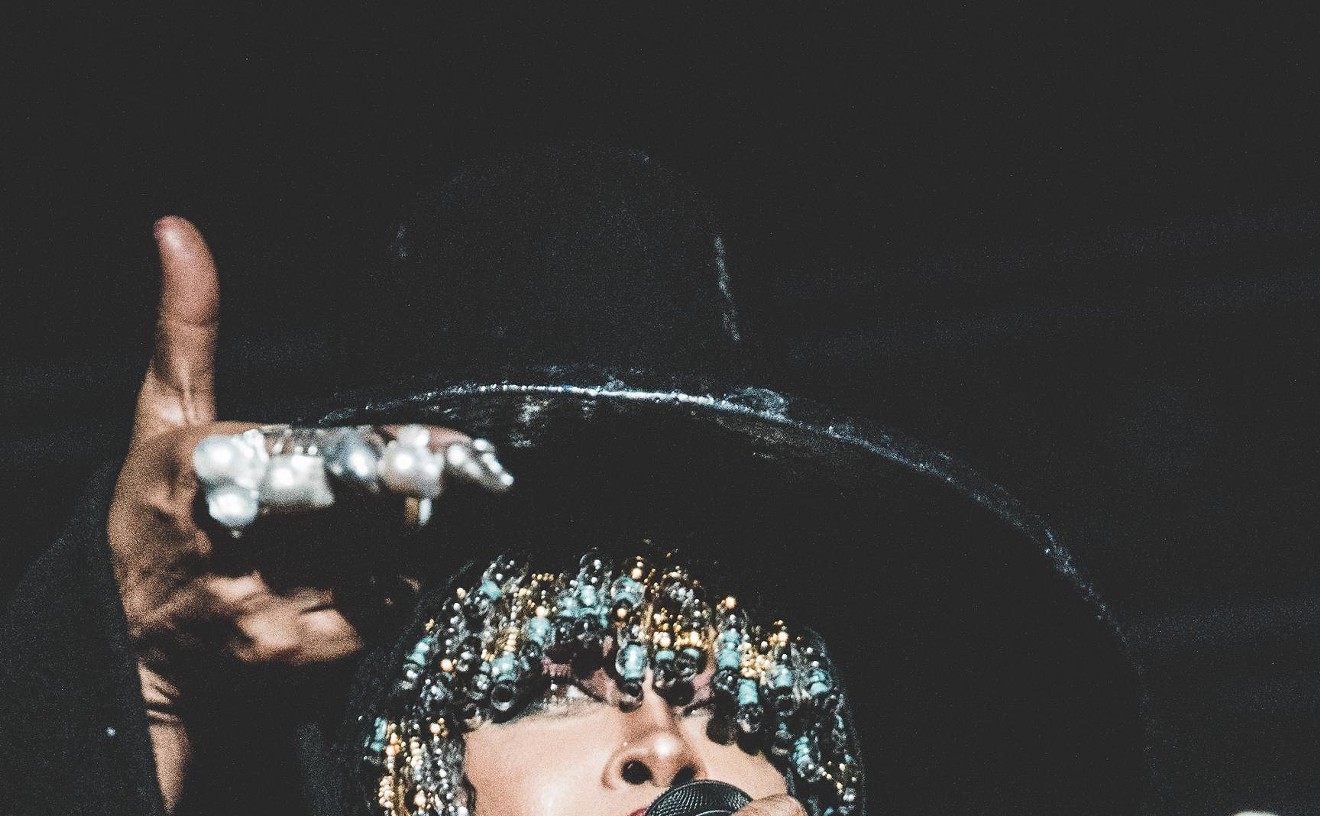

Rappers Buffalo Black, the Outfit, TX, Bobby Sessions and Lord Byron, among others, delivered unflinching albums that confronted the warfare on African Americans head-on, and were among the very best of any genre. It wasn’t just the recorded music, either: Sessions, who kicked off the year by releasing “Black America” — with its chillingly matter-of-fact chorus, “Life’s hard for a n*****” — on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, has taken to leading his fans through a show of solidarity during his concerts, raising first one fist for those who feel black lives matter and then the other for those who feel all lives matter.

Being a fan of Dallas hip-hop in 2015 has meant embracing hard realities.

“The shit happening now ain’t nothing new to me,” says the Outfit, TX MC Mel Kyle. He grew up in Pleasant Grove and attended high school in Mesquite, where he says he experienced police profiling at football games. Not much has changed in some neighborhoods since the 1990s. “I’ve been pulled over after parties and made to lay on the ground and searched, and they searched the cars,” he remembers. “If you’re black and you’re pulled over and you don’t know the laws, you’re fucked. We know this shit. You don’t even have to look at a TV.”

But Dallas hip-hop hasn’t always been so stark. Even veteran promoter Joel Salazar, who runs the monthly Fresh 45’s dance night at Crown & Harp with Spinderella and co-produced the We From Dallas documentary, says he’s never seen anything like Dallas’ socially conscious push in 2015. “I haven’t really heard much of that [before],” Salazar says. “It only seems like recently that artists have really started using their artistic platforms to get those messages out.”

Rapper Buffalo Black released his second full-length album, Surrilla, in September, and it dealt heavily with political and social themes. “Those topics mean a lot to me,” he says. “I’ve always addressed it in a way.” Black, whose song “Enter the Void,” was used in the trailer for Spike Lee’s Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, set the tone for Surrilla with lead single “1984,” a claustrophobic track that samples an interview with Angela Davis and depicts a world of Orwellian sloganeering and police surveillance.

Black agrees with Salazar that social media and the 24-hour news cycle have made the issues inescapable. “A lot of that has to do with just being informed,” he says. “When you’re being inundated with the same messages every single day — your Facebook, Twitter feed, Instagram — you’re probably going to feel like you have no other choice than to make a song about this.” But Black also thinks that the release of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly last March has helped to bring discussion of these subjects into the mainstream. “He pretty much crafted an entire album around those topics. I think that’s indisputably been very influential to everyone, to every rapper,” he says. Butterfly delves into Lamar’s personal emotional and psychological trauma. He speaks directly to fellow African Americans on a song like “The Blacker the Berry” and balances it with messages of hope on “Alright.”

In turn, Lamar, as Black puts it, has been portrayed as a “messianic figure,” one who articulates his struggle rather than politicizes it. “It’s a very powerful sense of encouragement when someone has been nominated like 11 times or so,” he says. Those nominations include Album of the Year and Song of the Year at the 2016 Grammy Awards. “There’s the issue with the content being so dark and heavy, and then it’s also kind of empowering because a lot of the content was really positive too.” The same is true of Black as well: A song like “Anomalies,” which features Lord Byron, sets images of oppression and violence against the backdrop of a beautiful melody and a search for self-affirmation.

It would be wrong, however, to say this is the first time Dallas hip-hop has committed itself to confronting social issues. Kyle says that’s a common misconception. “It’s more a reflection of a lack of infrastructure,” he insists. Dirty South Rydaz member Big Tuck delivered one of Dallas hip-hop’s most memorable lines — “We so for real here/Presidents get killed here” — nearly a decade ago on “Welcome to Dallas,” but harder-edged political verses are a poor fit for the dance floors. “The clubs have always been where you can count on to get your music spread to the people. You’re not going to take something more political or more lyrical to a club, you’re going to take something to make people drink and dance.”

In Dallas, finding concert venues that offer stages to rappers, much less ones with serious messages, has not been easy. Salazar says Deep Ellum has long shown a reluctance to book hip-hop shows. He points to Arnetic, which even hosted Lamar back in 2011, as one of the many hubs of local hip-hop that have disappeared, forcing the scene almost completely underground. That situation has gradually improved, thanks to venues like Trees being more welcoming. “That’s the swing of when this new age of younger artists were starting to get involved, and chronologically, it kind of fits when some of this stuff was really starting to push forward,” Salazar says. “For them, I think it’s more, ‘I have my spot now, I have my opportunity to speak out and I want to do it now.’”

Now more than ever, though, artists don’t need to rely strictly on the clubs to get their music heard. “At one time we had the radio but the radio just played the hottest songs from the clubs,” Kyle says. “With the advent of Soundcloud and shit like that, artists don’t just have to make that shit and count on Medusa or the DJs to play their music. They can upload it to Soundcloud.” The Outfit’s Down By the Trinity, as well as their earlier Deep Ellum EP, were both made available for streaming online without physical releases.

Those changes have gone hand-in-hand with what Salazar sees as a shift away from the traditional Dallas sound — a bass-heavy, boogie-style beat that puts the emphasis squarely on the turn up. That has as much to do with the emergence of producers like Blue, the Misfit as it does with a change among lyricists. Salazar points to the stabbing, ricocheting beat of “Black America,” which is far closer to a trap beat than anything of the Southern-fried, chopped and screwed variety, and which also shares its name with a song by Alsace Carcione. (Both were produced by Tone Jonez.)

“For the longest time, Southern rap wasn’t getting the respect it was due,” Salazar says. “The big theme of it was the sound — ‘We’ve got to have our own sound.’ I think more recently, they’re breaking the mold of that. It doesn’t have to be a sound, per se. It doesn’t have to be a Texas thing. It can be whatever you want to say artistically.”

The Outfit, TX is a prime example of how those different strains have converged in 2015. They dropped Down By the Trinity in late November, a murky, surreal album that took their women and weed roots and morphed them into a darker vision tortured by racism, poverty and violence. Kyle and his bandmates attended school in Houston and only moved back to Dallas two years ago, an experience he says was eye opening. “Blacks in Houston, they’re doing a little better, to be honest, than my people out here,” he says.

The sinister, 7-minute dirge “Revelations” paints the bleakest picture of life in Dallas, name checking Pleasant Grove and Oak Cliff in a drug-fueled vengeance story that uses gang warfare as a metaphor for systemic oppression. “What do I do when the rent’s due?” Kyle asks at one point, before repeating the line, “Hope nobody don’t say the wrong thing.”

But getting real about life in Dallas is just what Dallas hip-hop needs to do in order to grow. “It’s a sign of life when you have a hip-hop scene or rappers who are commenting on social events or providing social commentary. That’s the sign of a healthy hip-hop scene,” Kyle says. “It’s hip-hop’s job to narrate the times and narrate the community, and that’s what we’ve been doing.”

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18855504",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17105533",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17105532",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17105535",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]