He was also in the midst of a battle with Atlantic Records over the creative direction of the follow-up to his major label debut album.

That period of transition was nearly a decade ago. The song, “Disappear,” has been out for more than seven years, but that lyric continues to resonate with the latest ups and downs in its author’s life.

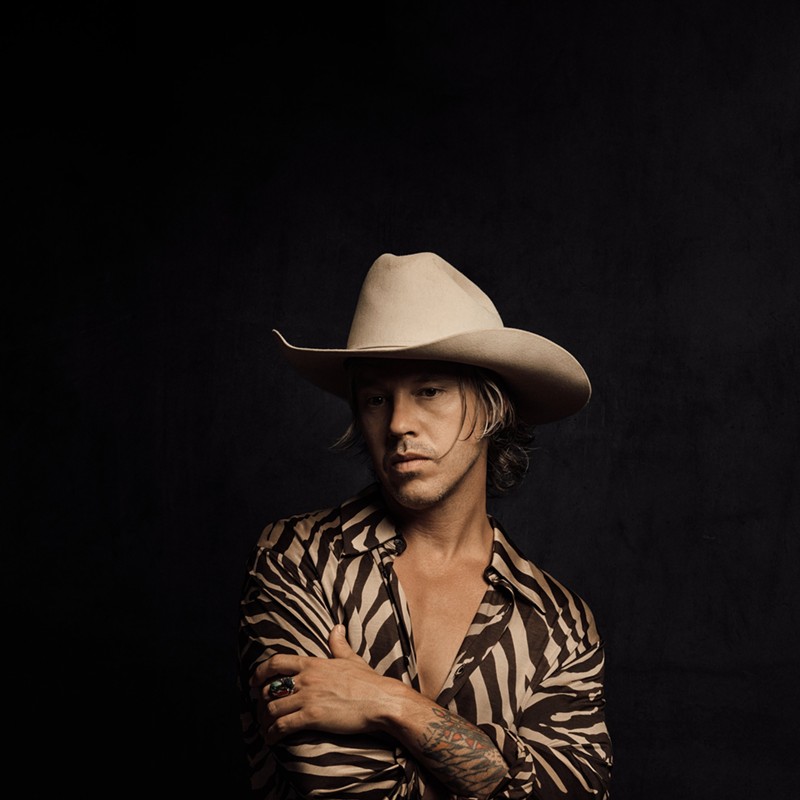

Tyler has just released Underground Forever, his fourth full-length LP and first in seven years. The 37-year-old singer-songwriter has been a fixture of the Texas music scene for more than 15 years now, since the independent release of his first album Hot Trottin’ in 2007 as a part of the five-piece rock band Jonathan Tyler & The Northern Lights. In 2009, JTNL signed with Atlantic Records, and the following spring, the band released its major label debut album, Pardon Me.

Today, Tyler is in a much different place. He’s cooking salmon and Brussels sprouts in his South Austin home, surrounded by plants, dozens of records, his dog Cash, his cat Boo, a giant taxidermy alligator and a whole lotta peace of mind.

“Crocodile,” he clarifies with a chuckle as he serves dinner, not disclosing much about the immobile creature that occupies about a fifth of his living room’s floor space. “It’s from Africa.”

As opposed to the chapters of his life that accompanied his previous releases — the naïve kinetic energy that fueled Hot Trottin’, the youthful exuberance that accompanied the major label backing of Pardon Me or the trial-by-fire rebirth that inspired his independent follow-up Holy Smokes — Underground Forever was born out of a growing dissatisfaction with the world around him as opposed to personal woes. It has subsequently led him to a place of great personal peace.

“I do feel like I’m in a good place, though it’s been work to get here,” he says as he cues up an album by Adrianne Lenker and runs his hands through his prematurely gray hair. “I’m still trying.”

Tyler is a curious interview subject. He seems more keenly aware of his answers and how they may be taken in and out of context than most contemporary musicians. While answering questions, he has a tendency to pause for longer-than-usual amounts of time to make sure that what he’s about to say is the correct thing. Any conversation with Tyler spins out into a fractal web of subjects, with tangents in abundance. Even then, he tends to end many of his more complex statements with words like, “I don’t know, man.” It feels as if there's an eraser-dust cloud trailing behind his words as he tries to soften their impact.

Sometimes he speaks in aphorisms, like “Rock ‘n’ roll, blues and country are all the same thing wearing different clothes.” Often, he's the one asking most of the questions — some directed at himself, some rhetorical.

Onstage, Tyler embraces neither rock star bravado nor folkie recluse. If anything, he is at his most vulnerable and awkward between songs. There's no golden god posturing, just the same Jonathan you get over breakfast and conversation.

Adorning Tyler’s house is an array of Western décor: hats, feathers, turquoise. Musical instruments, records and books line the nooks and crannies of the living room, with a massive studio-quality sound system at the front. It’s a fairly standard Southwestern home, other than the crocodile.

That record collection is a large and diverse one, full of the kind of staples you'd expect among any singer-songwriter or rock ‘n’ roller’s collection: Exile On Main St., The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, History: America’s Greatest Hits, The Faces’ Ooh La La, John Lee Hooker’s Endless Boogie, The Dark Side of The Moon. But there are also a few trippier colors in the palette: various albums by Yo La Tengo, Spacemen 3, Tame Impala, Beach House, The Brian Jonestown Massacre, Brian Eno’s Another Green World, The War On Drugs’ Future Weather, Grace Potter guitarist Benny Yurco’s instrumental solo album You Are My Dreams, Nick Lowe’s Jesus of Cool, Ruth Welcome’s Zither Magic and dozens of others.

While digging though his collection, Tyler pulls out an album called Vibe Killer by the band Endless Boogie, named after the aforementioned John Lee Hooker album. “Just give yourself an experience with these guys,” he says as he places the record on his player, hands me the sleeve and asks me to sit directly in front of the speakers in his "listening chair."

One of the pull-quotes on the record’s hype sticker reads "Pure Disgust."

“I am the vibe killer,” Tyler sings, growling along with the album.

Tyler has a particular obsession with what non-musicians would describe as "vibe." Unlike the social media concept of vibe as a lifestyle aesthetic, Tyler’s obsession is purely musical. He asks himself, "What does true vibe feel like?" His own records are rife with sonic detail that tickle the casual listener while pleasantly perplexing the ears of those listening deeper. There's the fuzzed-out, droning low note from a Farfisa organ on “Hustlin,” the envelope filter leading into the cosmos on “Moon & Stars,” the multi-tracked guitar harmonies on “Movin’ On,” the motorik new-wave-meets-metal-chug of “Mister Resistor” and numerous other moments on the record.

That sonic richness seems to follow Tyler, even into his own yard, where an orchestra of crickets and other insects rains down from the oak canopy and beyond. It almost feels as if the sounds are coming from the moon and stars, big and bright as they always are deep in the heart of Texas.

While Tyler is now in a place of relative comfort, the gestation of Underground Forever came during another period of transition. In 2020, Tyler and his longtime girlfriend, country singer Nikki Lane, broke up. In 2021, he was shooting the elaborate music video for his psychedelic ballad “Moon & Stars” when a romance was kindled between the singer and the video’s star, Zoe Prewitt.

“I try to make sense of every signpost that I see along the way,” Tyler says after a reflective long pause. “I’m always trying to make sense out of everything. We just hit it off making that video. It’s weird. You hear all these typical things people say, like, ‘When you’re not trying, you’ll find the right person,’ all those cliches. I don’t know, man.”

Of course he's heard himself say it too. “The time wasn’t right, but it never is.”

The Hype Was Real

The biggest storyline of Tyler’s career came in the wake of Pardon Me’s release in 2010. The album and singles found moderate success on rock radio via Atlantic’s marketing pushes. The single “Gypsy Woman,” Tyler’s then-signature song, reached a respectable No. 27 on the Billboard Mainstream Rock Charts. The band’s songs were featured in a few TV spots, and the band made a scorching appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live.

Produced by Jay Joyce (Cage The Elephant, The Brothers Osborne, Halestorm), Pardon Me is a slick and effective rock album that bridged that gap between early 2000s radio rock and the burgeoning blues and roots rock revival. JTNL’s mission statement at the time was a blunt and youthful one: “Baby, it’s been too long since rock ‘n’ roll turned you on, so won’t you pardon me?” Tyler and company sing on the album’s title track.

The hype was real: comparisons to early Kings of Leon were casually and constantly thrown around by the music press. At the 2009 Dallas Observer Music Awards, Tyler was named Best Male Vocalist, while JTNL took home awards for Best Group and Best Blues Act. In 2010, Pardon Me was voted best CD release by Observer readers, alongside a throng of positive national press. They played ACL Fest, toured with Lynyrd Skynyrd and ZZ Top, and opened for AC/DC in front of 9,000 people in El Paso. The band seemed primed for breakout mainstream national success.

Yet, that chapter of Tyler’s story has become a cautionary tale against getting caught up in what Joni Mitchell once called “the star-maker machinery behind the popular song.” Tyler found himself at odds with Atlantic, which was understandably looking to push him in a more commercial, "bro-country" direction. The songs he presented as the follow-up to Pardon Me were looser, folkier and more experimental than the Aerosmith-via-Black Crowes guitar swarm of his major label debut. What actually transpired is mostly between Tyler and Atlantic, but the resulting conflict prevented Tyler from effectively touring and recording for nearly five years.

Those songs were eventually released independently — in their true form, as Tyler wanted them — in 2015, making up his solo album Holy Smokes. Atlantic Records retained (and continues to retain) the rights to Pardon Me, making its existence in the wild a rare one, effectively only found on streaming services.

“We weren’t ready,” Tyler says as he pokes at his leftover Brussels sprouts. “We weren’t strong, we hadn’t built a strong thing yet, we weren’t even defined. But all these people at Atlantic got involved. It was too much, too quick. It’s not Ahmet Ertegun anymore, it’s all about data. It is what it is. What can I do about it?”

Ertegun, who was the head of Atlantic Records until the early 2000s, was known to give the artists on his label ample creative freedom.

To add insult to injury, Tyler was accosted by a Minnesota-based patent lawyer who demanded more than $50,000 for the rights to use the name The Northern Lights, a saga worthy of its own book. As the battle between Tyler and Atlantic raged on, the other members of the band moved on to other projects.

Just over a year after the release of Pardon Me, bassist Nick Jay left to pursue a full-time career in engineering and production (alongside a stint as a touring keyboardist for Ed Kowalczyk’s current incarnation of the band Live). Guitarist Brandon Pinkard and drummer Jordan Cain formed the duo Rise & Shine (whose Pinkard-penned song “Riverbottom” Tyler covers on Holy Smokes), with Cain also leading the roots-rock collective Atlantis Aquarius.

Pinkard eventually left the music business altogether for a career in construction, alongside JTNL’s full-time backup and occasional lead singer Emotion ‘Mo’ Brown, who also eventually left the music business to become a teacher. Given what JTNL was put through in the struggle with Atlantic, one can’t blame Tyler’s former bandmates for the change of heart.

“Some people don’t see the possibility of being able to [make music] for a living,” Tyler says. “You can work hard at a regular job for $200 a day, or you can come play music and possibly make the same thing, you just gotta play your guitar for three hours. Or, if you work real hard, you can land some commercial opportunities.”

After years of wandering through the landscape of the starving artist's path, Tyler found a job producing commercial music for a marketing company, a profession he says has allowed him to comfortably focus on making his own music while producing for others. It's a job he said helped rekindle his love for music.

“I tried to keep doing something that I loved while still being open-minded about other things,” he says. “It’s made a huge difference in my life.”

Tyler eventually regained the use of The Northern Lights name, and occasionally is still billed under his former JTNL moniker. Despite that, Tyler agrees that "Jonathan Tyler & The Northern Lights" refers to himself and that specific group of people — Jay, Pinkard, Cain, and Brown — and will generally be reserved for that group only.

“Brandon reached out recently,” Tyler says. “He reminded me that the ‘Movin’ On’ riff is actually one of the old Northern Lights riffs, and I was like ‘I don’t even remember that!’ But that riff had been something that Brandon had brought to the table back in the day, and I subconsciously kept it in the back of my mind, so ‘Movin’ On’ has an interesting [origin] from back then.”

Blue Skies, Dirt Road

Tyler’s music has always had a distinct dichotomy. It's the blue skies versus the dirt road. As the earthbound music reaches skyward, his airborne melodies seek the ground. The horizon that separates the two is an endless musical highway that vanishes into a single point. It's psychedelia meets Americana. The Bonnie-and-Clyde-esque tempestuous relationship duet with Nikki Lane on “To Love Is to Fly” from Holy Smokes is elevated by a bridge of pedal steel guitar through a wash of wah-wah and phaser effects, creating a sort of weightlessness that feels a lot like being in love.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t know what I’m doing,” Tyler and Lane sing to each other. There’s the gravity.

“It’s funny how if you write songs about something, sometimes you manifest that,” Tyler recently told an audience in Odessa, before playing “To Love Is to Fly.”

Tyler’s professional and personal relationship with Lane yielded one of her best records, 2017’s Highway Queen, produced by Tyler. Before their breakup, Lane also contributed backing vocals to several tracks on Underground Forever.

While Highway Queen was the first major record Tyler produced for an another artist, production has become the biggest part of his recording career. He's produced records for Jeremy Pinnell, Desure, Jeff Crosby, Kelley Mickwee and others, and in the near future one by Texas music legend Ray Wiley Hubbard.

“Jonathan is such a worker,” says Pinnell, whose 2021 album Goodbye L.A. was entirely produced by Tyler. “He doesn’t take breaks unless he’s totally fried. In the studio we worked and worked and worked. We would work until late in the night and he would keep going. We would call it a session and he would be back doing playbacks and tinkering with things. The vibe was so positive.”

Tyler has said he encourages artists to emphasize creativity before completion.

“It isn’t the Super Bowl,” he recently told Clarissa Cardenas on her Concert Queen podcast, discussing the coaching he gives to artists he’s producing. “It’s all right. Everything.”

“He is so good about encouraging people to try things and just draw it all out of you,” Pinnell says. “Like, you want to be around that dude! He’s good people.”

There is absolutely no shortage of love for Tyler in North Texas, Austin and their corresponding music scenes. Taylor Nicks, former frontwoman for Atlantis Aquarius, and currently of the noted Dallas music studio Modern Electric Sound Recorders, says Tyler was one of the first people to draw her into the local music scene.

Cameron Duddy, bassist of the Nashville-via-Texas country trio Midland, says his and Tyler’s paths first crossed in Music City playing a Johnny Cash tribute when Tyler gave him some mints.

"In the middle of this chaos, Jonathan gave me these Altoids,” Duddy recalls. “We didn’t really get to hang out, but later I was helping produce a record for Josh Desure and I invited him over to play some keyboards. Jonny’s really great at creating an overall vibe for an album that doesn't feel like you're listening to the same song over and over again, creating these textures that run throughout everything. Super underrated guitar player too. He's like Jeff Tweedy: unconventional and clever, a true student of theory — he’s hot and he’s smart.”

After a long break, during which Tyler focused mainly on gigging and producing, Underground Forever entered the world in 2019, and was more or less completed throughout the duration of the pandemic. Only one song and other minor alterations were made to the album prior to its release in November 2022, nearly three years after sitting on the shelf.

The album that was eventually released — containing the same songs — features a different track sequence from the finished product that Tyler originally had planned in 2020. His rationale for the change in sequencing?

“I shuffled the songs on my phone and liked the new order,” he says.

Though, by that point, more than half of the album’s songs had been released as singles, starting with the title track in April 2020 at the height of COVID panic. Obviously, Tyler didn’t know there was going to be a pandemic when he wrote “Underground Forever,” but throughout the first month of the lockdowns in late March and early April 2020, he realized that some of the songs he had written resonated thematically with what was happening in the world.

“I've heard songwriters forever talk about how a song is kind of in the universal subconscious or that ocean of subconscious that the world has,” he says. “It's going to hit somebody; somebody is going to write the song, it’s just whoever has the antenna out and catches the frequency first. The song is going to get out through someone, and it just so happened that I caught these songs. The whole thing felt like a premonition, because what I wrote ended up being pertinent to what was happening.”

The first verse and chorus of “Underground Forever” epitomize this, despite having been written a year before the world became trapped indoors: "We need a walk on the beach, or a picnic in the park,

we need an island getaway, 'cause things have gotten pretty dark. Can we hide out in the hills? Or sleep in 'till noon? I feel I’m gonna break if I don’t get out pretty soon. It’s all right, feeling uptight, there’s enough light, we’ll get through the night together. Windows down, leaving this town, never get found, going underground forever."

Tyler took advantage of the isolation and shot the cryptic video for “Underground Forever” in the nearly deserted streets of Austin to great effect. The video (directed by Justin Spence, Nikki Lane and Tyler himself) portrays Tyler tossing and turning at night to a seemingly endless array of television screens filled with pundits and commercials that ultimately feel like noise.

In the video, Tyler wakes up in the empty, almost post-apocalyptic vision of Austin wearing a tattered jumpsuit of the American flag. While searching the empty streets on his bicycle, he encounters a mysterious, sharply dressed secret agent (played by collaborator and fellow singer-songwriter Josh Desure), who provides him with a gold shovel. Shovel in hand, Tyler rides out to the wooded outskirts of Austin and begins to dig underground. Having dug a hole deeper than himself, he discovers a chest buried in the soil. He opens the chest, but its contents are never revealed to the viewer. Tyler simply takes his golden shovel and rides away, leaving the mysterious chest behind. As the song’s final chord melts from major to minor, the video fades from color to black-and-white. It's a musical question mark.

Tyler has described his latest album rollout many times as an “experiment” to learn whether an album can reach an audience completely organically, without a label push of any sort. He's repeatedly expressed disillusionment with the mechanics of the contemporary click-driven, TikTok-focused industry. While media burnout is a recurring theme in his most recent songs, Tyler never seems to take up an old-man-yells-at-cloud attitude. His stance is a wise yet cautionary one: He’s been there, done that, and the marketing machine is clearly not for him.

“The dream or idea is that if you make something that’s really great, it’s just going to get out there and people are going to hear it,” Tyler told Cardenas. “There are times where I believe it, and there’s other times where I’m like ‘there’s no way.’”

It’s in Jonathan Tyler’s home studio, which he refers to as “Clyde’s VIP Room,” where most of the magic happens. A small rear bedroom converted into a studio, the room is crammed with a bevy of equipment and memorabilia. A poster of Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen adorns one wall, while behind a drum set and a thicket of studio cables hangs a Telecaster autographed by Billy Gibbons, as does the American flag suit from the “Underground Forever” video.

“I try to make sense of every signpost that I see along the way ... I’m always trying to make sense out of everything." – Jonathan Tyler

tweet this

The room feels like a singular illustration of Tyler’s creativity, ground zero for his sonic and philosophical explorations — bigger on the inside than on the outside. Out in the yard is a garden area, and conspicuously lying on the ground is the golden shovel.

The background of Tyler’s computer is a still of the famous parade scene from the end of Federico Fellini’s struggling-artist masterpiece 8½, a movie Tyler calls his favorite. He queues up a demo track that he and his songwriter friend Jimmy recorded that same day; it's called “Models,” and it's about supermodels.

“Have you ever heard a song about models?” he asks with a laugh. “Me neither.”

Most of Underground Forever was recorded in California with producer Rob Schnapf, but one song on the album added late in the game was recorded off the cuff in Clyde’s VIP Room and became a sleeper hit of sorts: “Old Friend.”

The simple, mostly acoustic ditty is a sonic outlier on Underground Forever, yet it functions as the album’s emotional centerpiece. While the rest of the album is in motion, concerned with uncertainty, “Old Friend” is somehow nostalgic for the present, in a world constantly worried about the future.

“Someday these days will be worth remembering,” Tyler sings on the chorus. Given that the song was released during the beginning of the end of the dog days of the pandemic, it’s a welcome balm.

At the moment, Underground Forever is available only digitally, and unlike Holy Smokes, Tyler has yet to commit to a physical release. But for him that’s not an issue. Months after its release, “Old Friend” was getting 4,600 plays per day, without any kind of help from a label.

“There’s no marketing,” he says triumphantly of “Old Friend,” his experiment ultimately a success. “It’s all holistic. All grassroots. Just because people care. You can spend all the money on the sonic tinkering, but it’s all about the song,” he says, still beaming. “Although, I love the sonic tinkering.”

Despite having such a distinctive, dreamy sound in his own production — one that was put to good use on Holy Smokes — for Underground Forever Tyler opted to hand over production duties to Schnapf, whose CV includes Elliott Smith’s Figure 8, Toadies’ Rubberneck, Beck’s Mellow Gold and others.

“I love his albums,” Tyler says. “Sonically, I think he’s one of the best in the business. When you listen to songs like ‘Movin’ On’ and ‘Hustlin,’’ you can hear all the layers. Rob is unreal, he’s just a badass.”

To prove his point, Tyler puts on a woozy ballad recorded by The Vines and produced by Schnapf called “Autumn Shade II.” At the conclusion of the song, Tyler stands up and puts on his jacket as he prepares to lead the party a few blocks down the street to a watering hole called Sam’s Town Point.

Walking around Sam’s Town Point on any given night are a variety of musical individuals. Ramsay Midwood is playing tonight, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott might swing by tomorrow, and on this particular weekend, walking around is a singer-songwriter by the name of Sarah Lee Guthrie, a third-generation folk singer following in the footsteps of her father and grandfather — later revealed to be none other than Arlo and Woody Guthrie.

Alone at the end of the bar is Tyler, Altoids in pocket, with a rock-solid, enchanting grin, his face crookedly exhibiting amusement. He’s staring straight ahead, not even touching his drink. Above the entrance to the bar, a black-and-white sign reads, “Someday these days will be worth remembering.”

“Life’s like a frequency wave, you know?” he says. “They go up really high and they go down low. So everybody who acts like one way or the other, they have that other side. The downside is if you don't have a particularly high peak of one, you don't have particularly low value of the other. But it’s boring.”

Tyler stops to reassess whether he found the right word to make his point. “Well, maybe not boring,” he says. “But the passion of life comes from the risk and the reward.”

Tyler’s musical journey can be compared to the physical and emotional journey undertaken by Harry Dean Stanton’s reserved protagonist Travis in the iconic Wim Wenders film Paris, Texas, another work that juxtaposes the ephemeral with the real. It's the sky versus the road, it's wandering the wide-open spaces of West Texas on a voyage of discovery.

Tyler stands up and looks out the window into the noisy night, toward the direction of where the golden shovel might be.

“So, what have I discovered?”