It’s early on a Tuesday afternoon, and Toadies singer Todd Lewis is wiping down a new table in the entrance of his The Loop Artist Rehearsal Complex in South Fort Worth.

“We actually broke ground about 10 days before COVID hit, before the lockdowns,” Lewis says. “The guys who were working out here were considered essential, and they were not doing anything else. So, it went up in like a month. It’s been full ever since” he says.

It’s an inconspicuous building on Evans Avenue, across the street from a shuttered café and a small convenience store with hand-painted signs advertising beer, wine, ice and milk, and signaling that the Lone Star card is accepted there. Driving down Evans, you wouldn’t know you were in the right place if you'd missed the sign on the door announcing “The Loop” in all caps, and “Artist Rehearsal Complex,” below in fine print.

Even if you did notice the building and its inconspicuous sign, you’d never guess that this building had anything to do with Fort Worth alternative rock band Toadies.

Lewis’ is the only vehicle in the lot on the building’s north side until drummer Mark “Rez” Reznicek arrives, finding a spot to park toward the back where there’s still a little shade. Lewis sets down his bottle of surface cleaner and opens the door for his bandmate of 26 non-consecutive years and friend for over 30, and the two share a strong embrace, the kind two veterans who have served together might share knowing that nobody else has seen what they've seen.

It’s been months since the two musicians have seen each other in person as both have been pursuing their own interests as the pandemic’s long reach of lockdowns, postponements and cancellations has shifted the band’s Rubberneck 25th Anniversary Tour to what is now its 28th anniversary in real time.

On this particular day, the two are meeting to start planning rehearsals for the upcoming tour and share the history of the album’s surprising success and unlikely legacy.

I Come From the Water

To really grasp the unlikeliness of the Toadies story, you have to understand what the Fort Worth music scene was like in the late 1980s and early ‘90s.

As the Toadies tell it, there was virtually no market for a local band that played original songs, and the music exchange we see today between Dallas, Fort Worth and Denton was virtually non-existent.

“I mean, it was hard,” Lewis says. “Like there was no venue. So, if you wanted to make any money or even just get a couple of pitchers of beer as pay, it was covers and trying to sneak in your own songs.

“When we started playing, it was very cliquish; that was my perception,” he continues. “Dallas didn't want anything to do with Fort Worth, and so we reciprocated.”

Even as Pantera started to blow up in Arlington, Lewis recalls never having much to do with that scene as siloed as everything was. Even the Denton music scene was cold to outsiders.

“And, you know, people might play in all three, but they definitely seemed like their own separate domain,” Lewis says.

Much like today, the Fort Worth music scene was inextricably linked to the city’s university crowd, who were far more interested in singing along to songs they knew from the radio than hearing some band nobody ever heard of sing songs about brazen evolutionary creatures and creepy home invaders.

“Being a local band like that — that's just what it was — a local band,” Reznicek says, "there wasn't really a path to do anything beyond that.”

The Toadies found that path their own way, though, by “pissing off a lot of people and burning bridges” as Lewis puts it. Alternative rock was in its infancy, finding a home only in the speakers of the musically adventurous. Lewis and Rezincek counted themselves among those privileged ranks, finding inspiration in bands like Pixies and Talking Heads.

Lewis had been left angry by a breakup, and his bandmates in a cover band with which he played at the time held a kind of intervention, telling him, “Maybe if you stop listening to this [alternative] music and maybe start listening to this [rock] music, that would help.”

Lewis’s response? “How ‘bout you guys fuck right off. I’m going to go write songs. I’m really mad now.”

Looking back, Lewis is glad that he is not the angry young man he was in the years he spent crafting the 11 songs that would occupy Rubberneck’s initial release, but it was that push that made Toadies a decidedly original band regardless of its existence in an unwelcoming environment. It would be years before they would agree to even think about adding a cover to a live set, much less to a recorded work. I Crawled Upon the Shore

For Lewis, the memories of the band's early years are tied to one Fort Worth venue. "[The years] ‘89-‘90 was all up and down Magnolia [Avenue]," he says. " [Owners] Kelly Parker and Melissa Kuykendall had a place at the end, a one-story, glass-front building, and that's where ... ” Lewis struggles to remember the name before Reznicek chimes in.

“The Axis,” Reznicek says.

Lewis lights up. “Yeah, The Axis,” he repeats. “That was the original Axis.”

“That's kind of like the only place where a touring band or indie bands could play,” Reznicek says.

Some of those indie and touring bands would today be referred to as "classic" or "staples."

“We played with Fugazi, we played with The Lemonheads, played with Goo Goo Dolls, and it was like literally this size,” Lewis says, gesturing to one room that is about half the size of a shipping container, “maybe with a bathroom in the back.”

The Axis was similar to Parker and Kuykendall’s other venue, Mad Hatter’s, which served as the venue for the “Possum Kingdom” video, except that Mad Hatter’s was much nicer. Before Magnolia Avenue was the nightlife destination it is today, it was a row of empty warehouses and storefronts.

“It was kinda scary,” Reznicek says. “You’d go in, play a show and get the hell out of there.”

Somehow, in the midst of a musical desert, playing shows along the same street in one part of town, the Toadies piqued the interest of an A&R rep from Interscope Records. It was 1992. The band had just self-released a second EP, Velvet, and were trying to get it into the hands of as many people as possible: distributing it to local record stores, putting it on consignment at Sound Warehouse and sending some copies off to Reznicek’s cousin, who owned a record shop in Eugene, Oregon.

From there, the EP made it to a music distributor for the whole West Coast, who liked the album and handed it off to the same A&R rep who talked Interscope into signing Helmet — one of the first post-Nirvana, alternative rock band signings that happened after the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” music video changed the landscape of popular music and sent everyone out in search of the next big “grunge” band.

After that, the A&R rep came to Fort Worth to see the band, then flew the band out to do a showcase at the Whisky a Go Go in Los Angeles, where the president of Interscope Records heard them and signed them on the spot.

Grunge has always been something of a nebulous term that really had more to do with the look of musicians than it did with their music. Bands like Pearl Jam, Soundgarden and Alice in Chains were all labeled as grunge without sounding the same at all.

“What’s that dumbass saying,” Lewis asks, “'I don’t care what you call me, just call me?' I don't really care. I don't get it. In hindsight, visually, I get it because of the plaid and torn-up jeans, but that was just what we could afford, and it was everywhere. When the grunge stamp got put on us, I thought, ‘What happened to alternative?’”

Reznicek agrees. “All of those bands and us were more influenced by the Pixies than by each other,” he says. “They had catchy pop songs, but they were loud and heavy, angry songs … It’s all an evolution from the same stream.” I Left My Brothers There

By the time Rubberneck was recorded and made its way to the masses in August of 1994, the world had lost Kurt Cobain — the man who had become the de facto leader of this new genre — and the music world entered the beginnings of the post-grunge era.

Toadies already existed outside of grunge with a vocalist inspired by rock gods like Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant, AC/DC’s Brian Johnson and a few quirky little things from David Byrne. The sound was loud and distorted, but still poppy enough to be repeatable and memorable.

While not massive, the album was absolutely a success, peaking at No. 56 on the Billboard 200 and turning out two top-40 rock tracks with “Possum Kingdom” and “Away.” The Toadies were the biggest rock band to come out of Fort Worth since Bloodrock signed to Capitol Records in the 1970s.

When the band first set out on the road to promote the album, Lewis had every intention of returning to the record store where he'd been working for a year. Once the album went platinum in 1995, his plans changed.

That was the year that saw the “Possum Kingdom” video roasted by the titular characters of Beavis and Butt-Head on MTV. Butt-Head may have said it sucked, but most viewers must've agreed with Beavis when he said, "Give it a chance." The next year, "I Come From the Water" would find its way playing behind Chris Farley in a scene in Black Sheep.

As successful as they were and could have been, the group was a victim of its time and circumstance. Despite being one of the most original bands to come from outside of the Seattle music scene in the ‘90s, Rubberneck would ultimately be the only full-length album Toadies would release in the ‘90s.

“Not to take any blame away from the label, because I have a lot of animosity,” Lewis says, acknowledging the oft-told story of the seven-year gap between Rubberneck and its next release. “But our management kept us on tour for well over five years, and two or three of those years were 250-something shows a year. I mean, it was insane.

“At the time, I was not good at writing on the road. A lot of the new songs that we had after Rubberneck were used up on like soundtracks and compilations.”

With half an album’s worth of good songs lost to The Cable Guy, The Crow: City of Angels, Escape from L.A. and Basquiat among other movie soundtracks, and over five years gone by on the road, the band needed to start over completely but the momentum just wasn't there.

The band had a second album, Feeler, rejected by its label. Interscope also didn’t promote the Toadies’ third recorded album, which would be its second full-length release.

In 2001, the Toadies were no more — for a little while, anyway.

North Texans especially will remember the band's return with the first Dia De Los Toadies show at Possum Kingdom Lake in 2008, supporting No Deliverance.

The subsequent Feeler, Play.Rock.Music, Heretics and The Lower Side of Uptown would follow biannually with their own Dia De Los Toadies concerts until 2017. The band has toured extensively these last five years, but has stayed relatively quiet in the studio, with only a single here and a live album there. I Got What I Came for

It was July 6, 2022, when Lewis would find himself at home watching the latest episode of one of his favorite TV shows, For All Mankind, on Apple TV+.

“It's like an alternate history, and it goes all the way through the '90s,” the singer explains. “There's a scene in Season 3, where this woman is on a space capsule broadcasting music from that year and she cranks ‘Possum Kingdom!’”

"And they played a lot of it too," Reznicek adds.

Looking back on the Toadies’ career, Lewis admits there were some things the members could have done differently.

“You know, there was a couple of steps that we could have taken in hindsight to make that happen [to be a bigger band], but I'm happy with where we're at,” Lewis says.

But he won’t go so far to say that there are no regrets.

“There's some TV appearances that could have happened that didn't happen in there because of things in the band, and we didn't know, or even think about asking, for worldwide distribution right out of the gate," he says. "We're basically only known in the States and Canada and by diehard people around the world that might dig a little deeper, but when we were never on the radio or had our records released overseas.”

Regardless, the Toadies legacy lives on in new forms and new mediums, like the Bockslider Toadies Texas ale from Martin House Brewing Company that is still widely available five years later. There's also the self-published line of comics based on the image-heavy lyrics of songs such as “Tyler” and “I Burn” from Rubberneck, as well as “Jigsaw Girl” and “Queen of Scars” from later works. Each work, illustrated by Lee Davis, brings the song's story to life.

Reznicek has been busy with his own original comic series, which was recently picked up by Dark Horse Comics. Buzzkill is about a superhero troubled by addiction and fighting for the better good. The Toadies themselves appeared in two issues of Marvel’s X-Men comic series in 2016 issues 6 and 7.

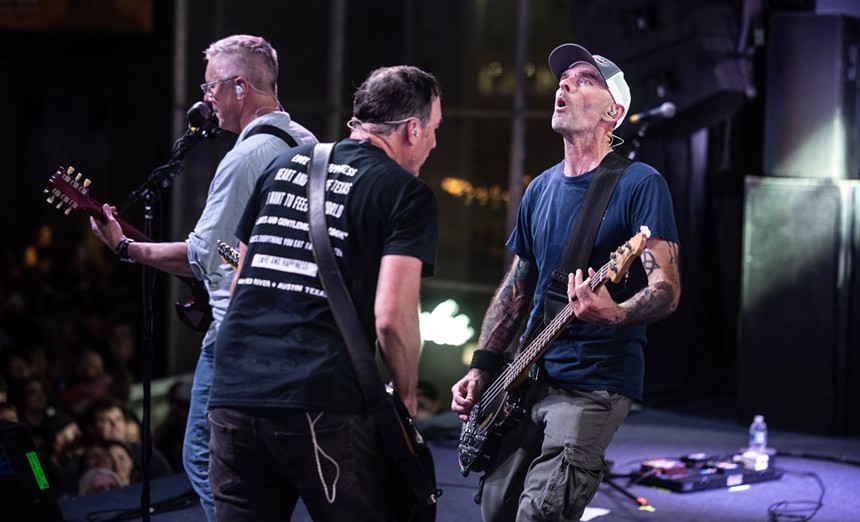

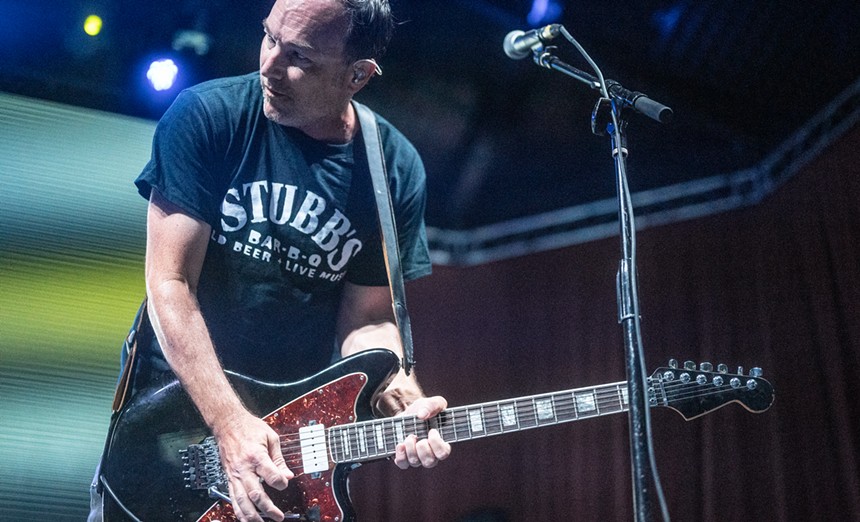

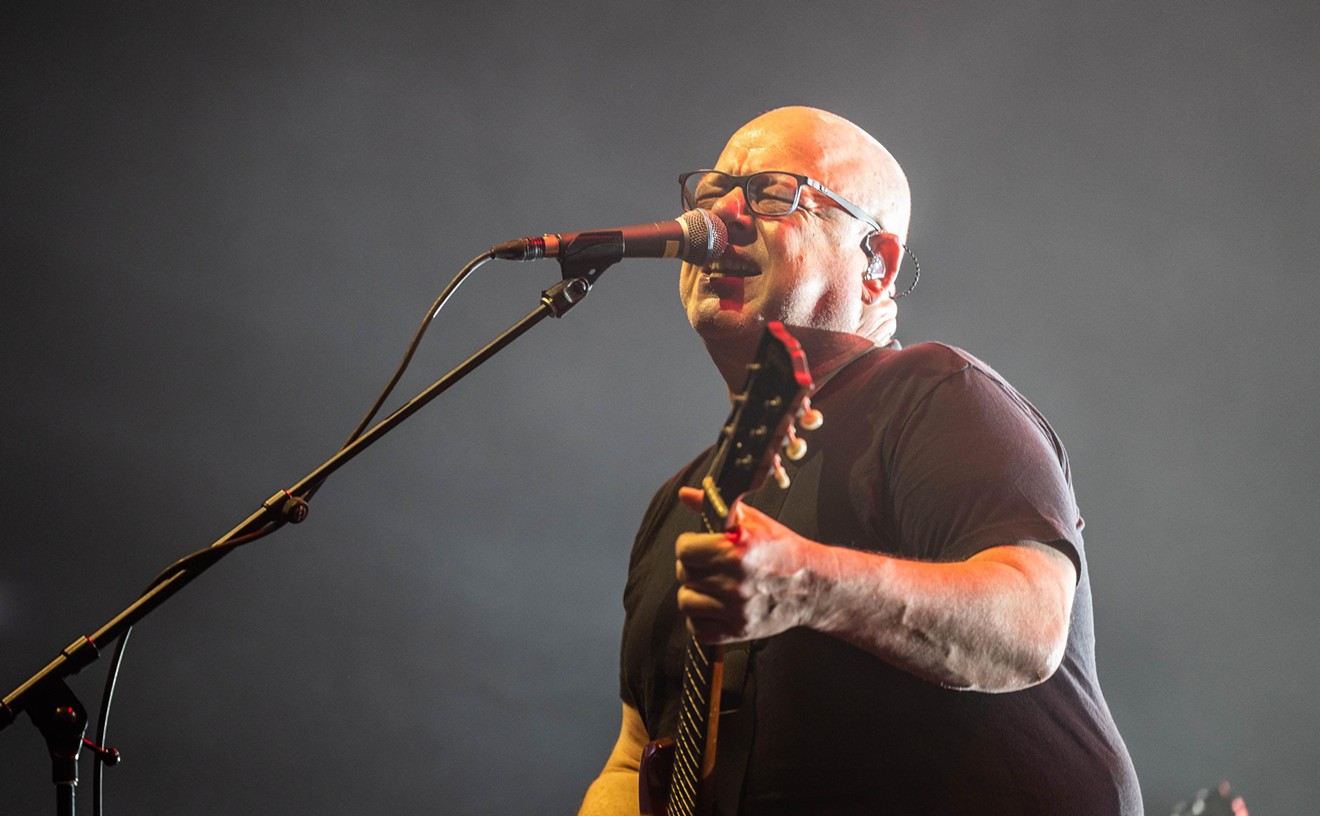

As for the live show, Toadies still has it. Lewis can still hit those high notes that made his voice stand out in a sea of deeper and raspier voices.

“I think I've maintained it pretty well,” he says with a smile. “Mainly, I've learned how to warm up with in-ear monitors. And taking care of yourself becomes way more important when you're not in your late 20s anymore.”

Now in the final days of its month-and-a-half long run, which has seen sell-out dates in Denver, Seattle, Pittsburgh, Boston and Philadelphia, the Toadies look forward to their first-ever show Friday, Nov. 11, at the House of Blues in Dallas with Doosu — a rare performance from Mike Graff with Mike Daane and Duncan Black from Course of Empire, Ugly Mus-tard, Andy Timmons and Moustrap.

An auction is planned to benefit Course of Empire’s former drummer Chad Lovell, who was also the longtime sound engineer at Curtain Club in Deep Ellum. Lovell has been hospitalized since a 2019 accident, and all auction proceeds will go to his family.

“Chad is someone who I always respected as a drummer and a sound engineer, and he’s a hell of a nice guy,” Reznicek says. “I’m a big fan of his intense style of playing drums, and his sense of humor is a constant source of laughter. I hope we can help in whatever way we can to ease the burden on him and his family.”

As the tour kicked off in September, Toadies dropped the first release since its last studio album, 2017’s The Lower Side of Uptown. The EP Damn You All to Hell contains four previously unreleased tracks, including a cover of David Bowie’s “Sound and Vision,” three songs recorded during sessions for the band’s last studio album, and “Forgiven,” which was recorded during the No Deliverance sessions in 2008.

But that’s not all the Toadies have in store for fans. The group is currently working with legendary alternative rock producer and engineer Steve Albini, who has lent a hand to iconic albums from Pixies, Helmet, The Breeders, Jesus Lizard, PJ Harvey and Nirvana.

“Hopefully we'll see him on this tour when we go to Chicago — that's the tentative plan,” Lewis says. “If it works out, if he's still available and we're available and we have the material at the right time, then yeah.”

Acknowledging the Toadies' history with having the best laid plans, Lewis adds, “Or wait seven years and then see if anybody's still paying attention."

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18855504",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17105533",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17105532",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17105535",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]