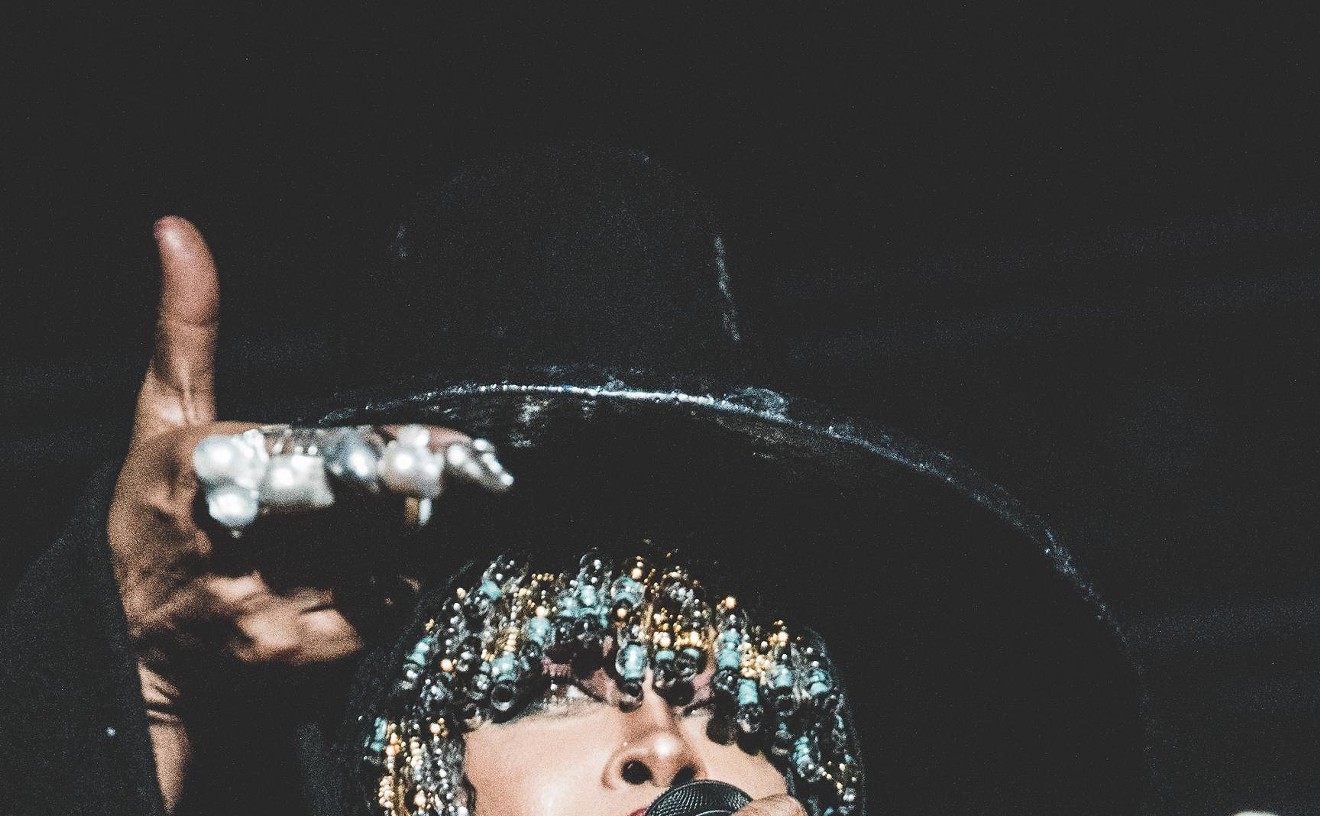

The woman sitting comfortably in the uncomfortable chair doesn't have to do anything; she dresses up the office just by being in it. Shrink-wrapped in denim, N'Dambi looks like a star, wearing the casual elegance of the girl-next-door who just happens to be very rich or very famous. She's not either of those things, but she should be, and would be if we lived in a world that made sense instead of dollars.

In that world, fans would stop her in the street, asking her if she's who they think she is, asking for photographs and autographs, maybe just a hug and a smile. She wouldn't be sitting here talking about her new album, the fantastic, double-disc Tunin Up & Cosignin, a mix of old songs done in a new way and new songs that sound timeless. Too many people would want a piece of her time. She definitely wouldn't be here with only her manager-partner, Odis Johnson, in tow. There would be an entourage--assistants, publicists, stylists, friends, family.

Yet here she is, because this is your flight path when you're flying just below the radar. You pack into a 15-passenger van and make it happen for yourself, by yourself, talking to anyone who will listen, singing to anyone who cares. It's especially true for R&B performers like N'Dambi, when setting up shows is a jigsaw puzzle assembled by people who shouldn't have their hands on the pieces. As N'Dambi says, a start-up rock band may be able to luck into a few opening dates with a bigger act, catch a few breaks, but a soul singer rarely comes across such opportunities, not until it's too late.

"Everything is monitored by what's your name, who you're associated with and how can they make their money," she says. "They don't want another female opening, or there's too much competition, two males can't open on the same show--it's catty stuff that gets in the way of why you don't find out about the real good R&B performers until they're dead and gone. They're gone into obscurity, and then you start talking about Shuggie Otis and people like that, who did some good music."

She won't have to wait quite so long. At least you'd hope not. Already, she's beginning to escape the shadows, slowly, surely moving into the spotlight. Maybe you've seen N'Dambi before, in videos, on television shows, in the pages of Vibe and Elle and Vogue and Harper's Bazaar and Billboard or one of the other dozen magazines in which glossy photos and glowing write-ups of her have appeared. But you probably don't really know who she is yet, even if you've seen the pictures and read the words. She's not the next Macy Gray or Alicia Keys or Lauryn Hill or Jill Scott or any of the other new soul singers with whom journalists and record company execs seem determined to compare and contrast her. She's the first N'Dambi.

"We're all doing different things, but because people don't really have a good gauge of what soul and R&B music is, and they want to call it 'neo-classic soul,' and they have to build a category for you to make your music in, then we all get lumped in together," she explains. "I don't think Alicia Keys does anything like what Jill Scott does or anything like Macy Gray. They're all different kinds of artists. But they're all in one category."

More important than any of those recommended-if-you-like comparisons, N'Dambi (born Chonita Gillespie) is from right here, born and raised in Dallas. Grew up near South Oak Cliff High School. Was in the choir at Oak Cliff Baptist Church, where her father was a minister. Went to high school at the business magnet, even though she was a skilled enough piano player to go to Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing Arts. Graduated from Southern Methodist University with an English degree.

Here's why you probably don't know any of that yet: Instead of waiting for a record label to discover her, N'Dambi discovered herself, releasing her debut album, 1999's Little Lost Girls Blues, on Cheeky-i Productions, the label she started with Johnson. She went out on the road, putting herself and her songs in front of anyone who'd listen. When she was done, N'Dambi had sold around 70,000 copies of Little Lost Girls Blues, and her face turned up in more magazines than subscription cards or free AOL software.

But in Dallas, her hometown, this beautiful, talented, independent woman is virtually anonymous; the only "Independent Women" you're likely to hear on local R&B radio is the song by Destiny's Child. You won't hear the singer with a voice floating like smoke over the nightclub where soul, jazz and gospel get together after hours, singing blue notes above the choir, putting the sultry rhythm and been-there blues back into R&B. Which is a shame. Tunin Up & Cosignin is a late-night jam session with Nina Simone at the microphone and Stevie Wonder behind the keyboards (see: "Lonely Woman/Eva's Song," which opens up disc two); it contains 18 examples of a young woman finding her own way down a very old path. It deserves, demands, to be heard by everyone with ears and a soul. Dallas radio, typically, isn't hearing any of it.

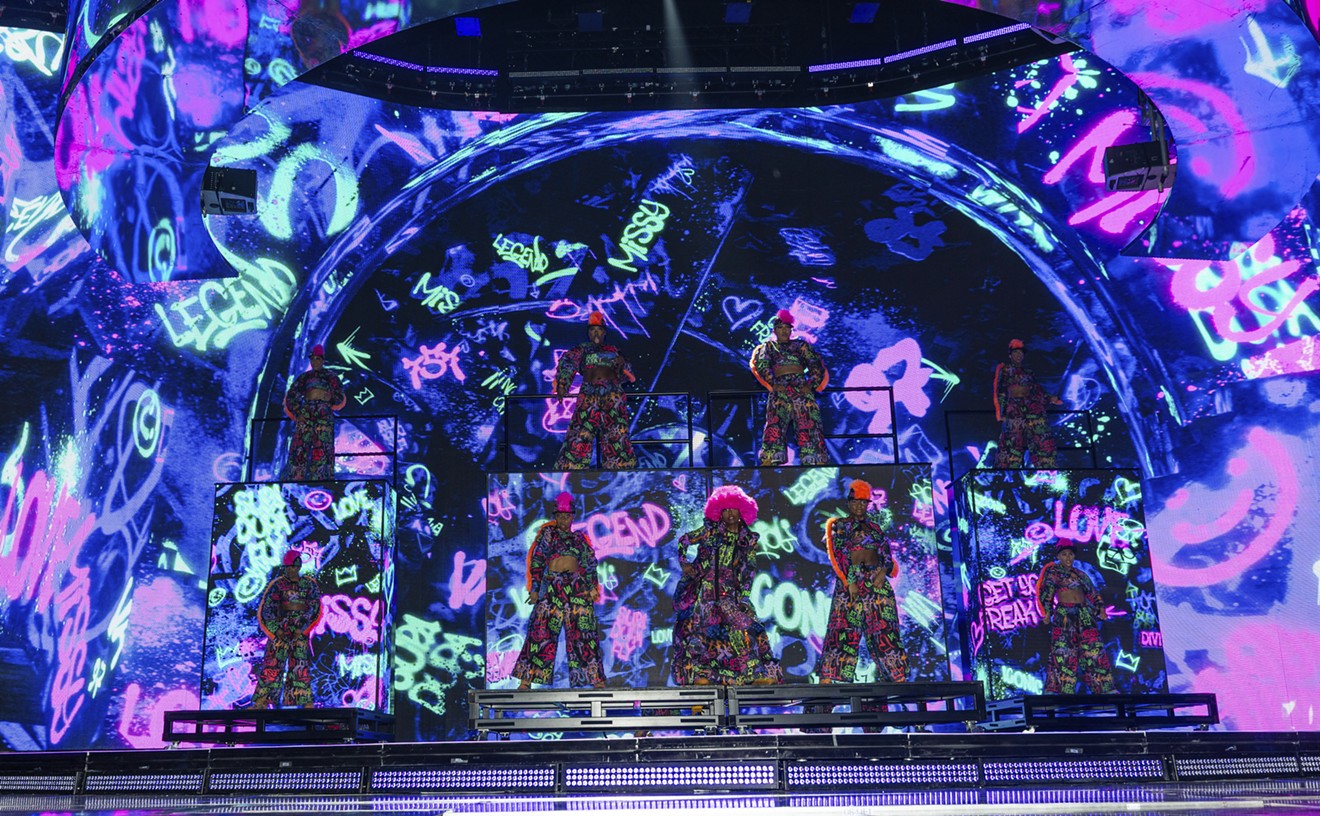

"They wait until you blow up, and then they claim you--our own. 'We supported her...' That's what they do," N'Dambi says, laughing a little. She's seen it happen before: Her friend Erykah Badu--with whom she has toured, singing backup vocals--had to prove herself elsewhere before local radio stations started paying attention. "That's exactly what they do. It's unfortunate. That's the reason why it's important to keep it independent. We can show other artists that they can do music, and they can make the kind of music they want to make, without the support of those things they think they have to have. Of course, there are a lot of sacrifices in the process, and that's the problem. A lot of people don't want to make those sacrifices; they want to be comfortable. Sometimes you have to be uncomfortable to get to a really comfortable position. Sometimes they don't want to do all of the work."

N'Dambi has never been afraid to be uncomfortable, even performing with her leg in a cast at a concert in New York in May. But it's a different kind of comfort she's talking about, of course. Originally, Little Lost Girls Blues was supposed to be a calling card, something to send to labels in an effort to sign a recording contract. She already had some interest, thanks to her stint backing up Badu. Soon enough, though, N'Dambi and Johnson realized they didn't need anyone but themselves. So they took a chance and put the album out on their own label, hoping her talent would get them through the tough times that surely lay ahead.

While Dallas is still catching on, it wasn't long before Little Lost Girls Blues found its audience, even traveling overseas, where fans began paying high import prices just to hear it; the disc was never officially distributed in Europe. Fans began creating Web sites dedicated to her, trading MP3 files over the Internet. (Here's what the Recording Industry Association of America won't tell you: Napster and other file-trading software actually help independent artists.) Though it's wrong to lump N'Dambi in with fellow travelers like Macy Gray or Jill Scott or Lauryn Hill, their presence made listeners more receptive to what she was doing down in Texas. "Now, 'neo-classic soul' is trendy," N'Dambi says. "So because of that, people are looking for anything that might fit that category."

Even though she was happy with the interest in Little Lost Girls Blues, as soon as N'Dambi began playing live, she knew she didn't get the album absolutely right the first time. Actually, she thought she got it too right, that it sounded too much like music made in a studio instead of just music. For Tunin Up & Cosignin, she brought in live musicians--bassist Braylon Lacy; drummer Gino "Lockjohnson" Iglehart; keys players R.C. Williams, Shaun Martin and Geno "JuneBugg" Young; trumpet player Leon Devers; vocalist Andrea Wallace; saxophone and clarinet player Jason Davis--most of whom were in her touring band. They also grew up with her, went to the same church. It's a bond that comes through on every song. And it's a bond that meant they didn't have to spend too much time getting it on tape. If there were mistakes, that was fine by her.

"I wanted to be kind of imperfect," N'Dambi says. "With all the creaks and cracks, not going back and overdubbing anything, all that stuff. I wanted it to feel like they used to make music back in the day: They'd go into the studio, and be like, 'I only have $30--how many hours can I get for this music?' Like jazz musicians and stuff. And they made a song, and they did it good, but they'd only take a limited amount of time to do the music. So we tried to keep it a limited amount of time as well. And I think that it works best for me to work with limited time to make an album. Instead of having a whole bunch of time, and playing around, because then I'll change it. I'll listen to it over and over and then pick it apart."

The result is a pair of discs that revisit the recent past (11 songs from Little Lost Girls Blues show up on Tunin & Cosignin) and obliterate it, clearing the slate for a brand-new future. It's a studio album, yes, but it lives on a stage, with a set list made up on the spot of jazz standards, soul classics and everything in between, no one knowing where they're going but all getting there at the same time. Tunin & Cosignin is a record that needs to be listened to from beginning to end, just like a concert. Which is exactly what N'Dambi was after.

And what she says goes. After all, she is the boss, both band leader and label co-owner, a position she doesn't sound ready to give up just yet. Other labels have been calling, but she insists she would never sign as an artist. She might sign a distribution deal, but she likes being the boss, in control. And she knows she doesn't need a label deal to make her successful. That's because she already is.