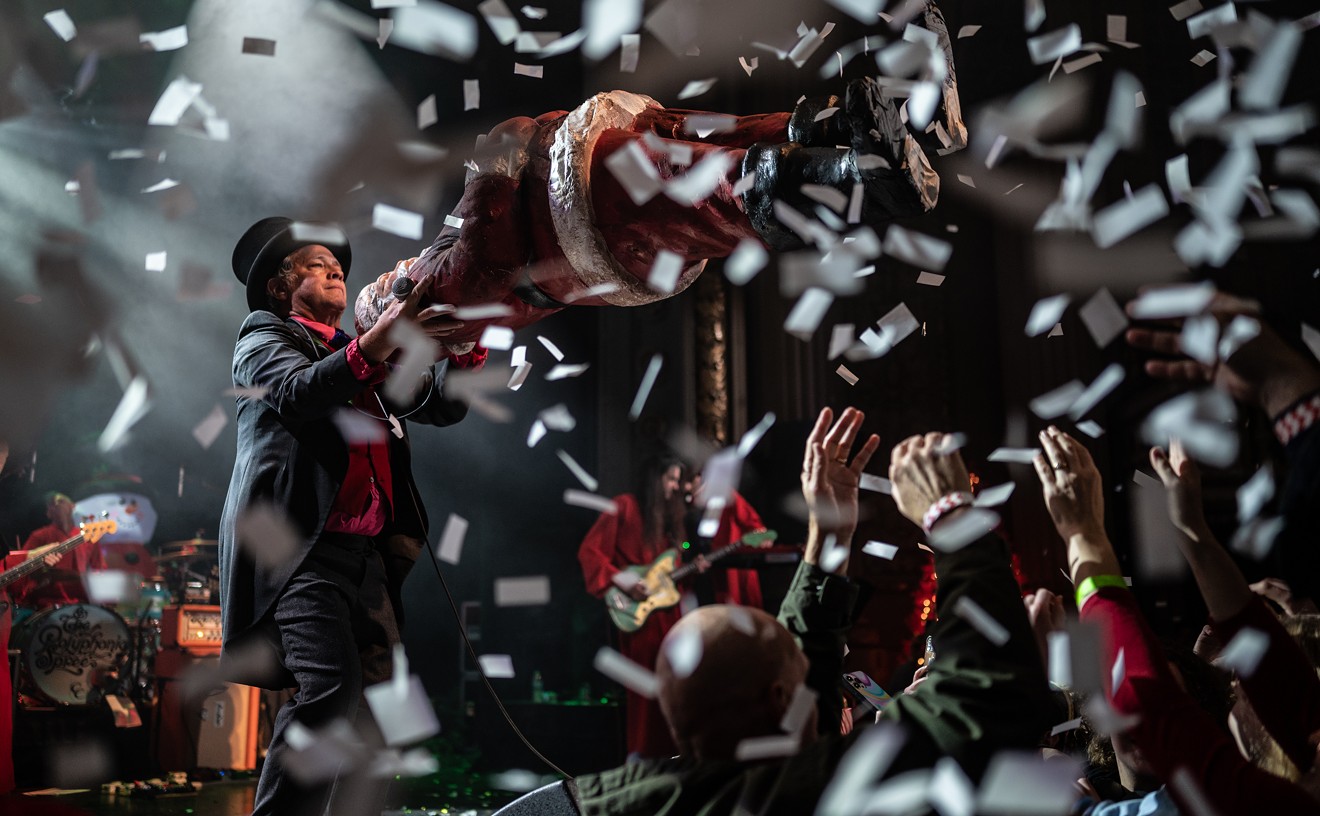

With arms outstretched and one hand clutching a microphone, Dezi 5 mounted himself on a wooden crucifix at The Public Trust, an art gallery in Dallas' Design District, as a projection bathed him and the makeshift stage in colorful light.

Dressed in fishnet T-shirt and black vinyl, Dezi 5 performed songs off his EP, Crucifixion On the Dance Floor, from his perch on the cross. His goal that night in the late summer of 2015 was to “crucify” his insecurities of having grown up a gay black man in Dallas. And he did it all thanks to show promoter Vice Palace, which organized the show.

“We had a long conversation about the possible backlash he may face from that,” says Arthur Peña, the founder of Vice Palace and its Vice Palace Tapes cassette label. “I said, ‘Look we can't have this show in a warehouse, we need the gallery to frame it,’” he says. “This performance was a vessel for conversation to happen. When Dezi gets up there and crucifies himself, the conversation that surrounds that is way bigger than Vice Palace.”

That was the beauty of the self-proclaimed “roving venue,” which is now shutting its theoretical doors after three years. It pushed the envelope and provided a safe haven for the underground scene as it bridged the gap between the art and music worlds, and it threw all genres of music together under one roof. Those roofs were mostly warehouses in its first year, but the brand evolved into holding shows in mainstream places like Josey Records, the Texas Theatre and Three Links in its second and third years.

“It can't really close because it's more of a spirit and an energy than anything,” says Peña. “But I’m not going to be doing Vice Palace as a roving venue or trying to pull together shows.”

Peña describes it as a “roving venue” because it didn’t have a permanent physical space. Early in 2015, he added Vice Palace Tapes into the equation, which recorded live performances at shows — including ones by Bludded Head, Party Static and Dezi's show at The Public Trust — and produced the recordings on cassette tapes with funding from a city grant.

He says the decision to stop doing shows and recording tapes was mostly financial, rather than due to pressure from the fire marshal shutting down performances and art events. The $5,000 in grant money ran out, and he was selling the tapes for only $5, so he wasn’t recouping costs on producing them.

“I can’t keep putting money into it. Music labels are expensive,” says Peña. “The way Vice Palace Tapes operates, the artists don't pay anything. It’s either the grant money or I pay for it out of my own pocket.”

Vice Palace is holding four shows in November, and each show will feature a different cassette tape release. That would have been the end, but recently, Peña was awarded a faculty grant from SMU Meadows School of Art, where he’s a visiting lecturer in painting.

The grant will fund the music label through the spring of 2017, and Peña is planning to have a series of shows or perhaps one big party for the purpose of recording the last batch of cassette tapes. He thinks he’ll focus on hip-hop artists and electronic acts.

“I always thought Vice Palace should last three years to have any real impact, so it's sort of preordained in a way,” says Peña. “The grant from SMU is the X factor. … If I didn't get that grant, it just would have been all done.”

To date, 14 artists have been recorded across seven tapes. Stefan González is one of the musicians whom Peña featured in Vice Palace shows and who’s recorded on one of the cassette tapes under his one-man solo experimental act, Orgullo Primitivo. On the day of González’s interview, he was on his way to Aqua Lab Sound recording studio in Deep Ellum to mix down his performance for the tape.

“[Peña] blurred the lines between performance art and visual art and music,” says González. “I knew him as a visual artist, and then he started throwing shows, and shortly after asked me to play a big warehouse show he threw. He became an ambassador of culture around here, smashing divisions and bringing people of different backgrounds together for one cause. Vice Palace is really about transcending cliques. What he did was really important.”

González runs Outward Bound Mixtape Sessions at RBC on Monday nights. It’s a live music mash-up featuring lesser-known artists from all genres, so González is no stranger to the underground music scene in this city. He says Vice Palace even influenced his work with Outward Bound.

“He gave me the opportunity to play in front of hundreds of people. They were intrigued and started coming out to Outward Bound or checking out other bands that I've played with. I'm still gliding off of that,” says González. “It's also helped me reach across to other people I might not have known or I'd seen only in passing,” he adds. “I'm sad to see it go, but more than anything I'm glad that it happened.”

Peña says Vice Palace will happen again if and when it needs to. But the closures by the fire marshal are making it nearly impossible for these types of cultural events to happen.

“Vice Palace would have never existed in this climate. To look back and see what it's done, and how many people I got to work with, and how many people met — to think all of that wouldn't have been available to the people of Dallas,” says Peña. “They’re shutting down any sort of potential framework for a community to grow and cultivate itself.”

Overall he looks at Vice Palace as a service for Dallas, not only because it put artists’ music on the cassette tapes free of charge to them, or because it brought the disparate art and music scenes together, but also because it functioned to document the current music scene.

Peña had a videographer record all of the live performances and he is working on putting together a documentary and perhaps posting all of the full-length footage on Vice Palace’s Vimeo channel as a sort of time capsule of each of the shows.

“I'm more focused on recording and documenting,” Peña says. “I get much more pleasure in knowing I had a role in indexing not only the history of Vice Palace, but also Dallas' music history.”

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18855504",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17105533",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangleLeft",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangleRight",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17105532",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangleLeft",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangleRight",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17105535",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]