OK, you white? Then here's something neither one of us knew. Back in the day, black kids had their own secret tunnel into the State Fair of Texas.

No, no, don’t tell me I’m making that up. It’s true. If you want the full skinny on the secret “Three Man Tunnel” — not to mention a wonderfully evocative window on racial desegregation in Dallas through the eyes of children — you need to go here and listen to the BBC.“One day they asked us had we ever saw a play called The Nutcracker. We said no. So they called us to the auditorium, locked all the doors, made us watch this thing."— Melvin Qualls

tweet this

It’s a haunting saga entirely in sound, produced for and recently aired by BBC Radio4, a branch of the British Broadcasting Corp. You can stream it.

Called Lights Out, Big Tex, it’s the story of Dallas in the years of school desegregation as remembered by people who lived through it as children. The irony for us in Dallas is that this production, which will be heard mainly by people in Europe, is so much more effective a portrait of our own city than what we are exposed to here regularly.

What we get here is a well-deserved battering. Dallas public schools trustee Miguel Solis had a great piece yesterday on the op-ed page of the daily paper calling attention to two important recent batterings.

The first one Solis wrote about was the recent visit of Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Rothstein spoke to an audience at the University of North Texas at Dallas College of Law. I attended, and I felt very battered afterward.

Rothstein’s book is national in focus, not about us in particular. He lays out in painstaking detail the explicit heavy-handed edicts, rules and even laws the federal government imposed on America after World War II, not merely to preserve racial segregation but to impose it afresh in places that had not been racially segregated before the war.

Rothstein shows with facts and figures that there was nothing accidental, coincidental or serendipitous about the racist pattern of post-war residential development in American cities and their suburbs. Racial segregation was imposed through explicit governmental actions, the social and political equivalent of razor wire, guard towers and machineguns.

Count me battered.

The second battering in Solis’ essay is something we have discussed here before on several occasions — the parade of rigorous academic studies that find the degree of racial and economic segregation in Dallas to be far higher, far worse than in most equivalent American cities. Call me battered again.

Those studies, which just seem to keep rolling in on us, are one reason I sort of choked a bit yesterday when I saw the just released, previously secret description of Dallas’ failed bid for the Amazon so-called “second headquarters.” In a memo to the City Council released yesterday, City Manager T.C. Broadnax said Dallas, as part of its bid, had told Amazon it wanted the gargantuan global retailer to “commit $100 million in local investment toward addressing race relations, green space creation, and poverty.”

I figure whoever read that line at Amazon probably turned to an underling and said, “Hey, go look up race relations in Dallas.” If so, we know what was found. And we wonder why they stayed away?

The batterings are important. We need the batterings, especially the ones based on research and incontrovertible fact. Solis quotes James Baldwin: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” So, yes, we must face the grim reality of racism and racial segregation in our city.

The problem with facing it, however, is that facing it is not necessarily the same thing as feeling it. That’s why the BBC Radio4 piece is so wonderful. Produced by Hannah Dean and Alan Hall of A Falling Tree Productions with research by Paula Bosse, Lights Out is presented by Julia Barton.

Barton is a radio producer in New York who grew up in Dallas. In this piece she tells her own story as a kid at Alex Sanger Elementary School in Dallas in the mid-1970s when black children were bused to white schools under federal court order. Barton went back and found some of her black friends from those days and got them to recount their memories.

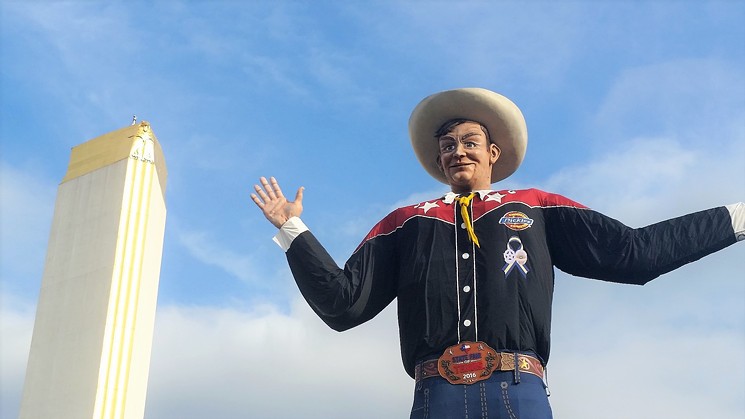

Big Tex was as big a symbol of Texas pride to the black Texas kids who had to sneak into the Texas State Fair by way of a secret tunnel as he was to the white Texas kids who came in through the front gate.

Jim Schutze

With the theme of the sugar plum fairy tinkling ironically behind him, Melvin Qualls, now a middle-aged man, recounts what it was like for him as a little boy:

“One day they asked us [the bused black kids] had we ever saw a play called The Nutcracker. We said no. So they called us to the auditorium, locked all the doors, made us watch this thing."I didn’t look at it as, ‘That’s a big white man.’ I didn’t look at it as, ‘That’s a symbol of oppression to our people.’ I looked at it as, ‘I’m a Texan, and he’s a Texan.’ It was a source of pride."— Sam Franklin

tweet this

“To me it was like six hours long. I did not understand one thing of it. All I knew was that they said it was called The Nutcracker. It was something about what you would call courtship.

“We all got locked in. They locked all the doors. We couldn’t get out. They had people outside the doors. You couldn’t use the restroom, you couldn’t do nothing. You had to sit there and watch this play.”

Looking back now, we must wonder what the aim could have been. Was it a message? Like, “OK, you black kids, this is white culture. You sure you want to be here?”

The memories of white people from the period are more caustic. A white teacher recalls how one of his white colleagues summarized desegregation: “You can take a spoonful of chicken droppings,” the colleague said, “and stir ‘em in a gallon of ice cream, and it won’t hurt those chicken droppings one bit.”

Another voice in the program is Dallas historian Donald Payton, who recounts a story he told me and I included in a book more than 30 years ago — the infamous dunking booth at the State Fair. The attraction was a black man on a seat dangling above a water tank:

“I can remember a guy named Red who used to work in the dunking tank,” Payton says. “Boy, he could agitate them white men, could agitate them! They would be buying baskets of balls, a line of them. ‘Hit that trigger and dunk that nigger!’”

Sam Franklin, left, gives an interview to radio producer Alan Hall about Dallas in the time of school desegregation.

courtesy A Falling Tree Productions Ltd.

The kids called it the “Three Man Tunnel” because it split three ways. You had to know which way to go to find your way to the opening and not get lost forever.

Sam Franklin, who now works for the Dallas Park Department, recalls that, once inside the fair, the emotions the black kids felt were joy and awe. He describes his feelings about Big Tex, the giant white cowboy figure who greets visitors with a signature “HOWDY, FOLKS!”

“In every project home,” Franklin says, “there was a picture of Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy and a picture of white Jesus on the cross. In every one of our homes.

"I didn’t look at it as, ‘That’s a big white man.’ I didn’t look at it as, ‘That’s a symbol of oppression to our people.’ I looked at it as, ‘I’m a Texan, and he’s a Texan.’ It was a source of pride."— Sam Franklin

tweet this

“And so when we went to the fair, I didn’t look at it as, ‘That’s a big white man.’ I didn’t look at it as, ‘That’s a symbol of oppression to our people.’ I looked at it as, ‘I’m a Texan, and he’s a Texan.’ It was a source of pride, because it was Big Tex. It was big Texas.”

Right there, in those few words, lie the enormous pain and joy of this story, a tale of ingenious pesky little kids tunneling to the light, protected from the cruelty of adults by their childish incapacity to comprehend it. In the end they tunnel their way to the joy of life, to the basic dignity and fullness of experience that the adults had tried to keep from them.

You gotta go listen to this thing. It’s the thing without the battering.

Oh, there might be a very mild bit of battering about it, I guess. Barton doesn’t sugarcoat anything. She explains at the end that the response of white people in Dallas to school desegregation was to flee en masse. And, indeed, the white defection here was a kind of refugee movement akin to the Cubans who fled Castro in the 1950s. So in that sense court-ordered desegregation failed to achieve its end.

Or did it? Barton closes by saying, “The gift that desegregation gave to me as a white person was that it revealed the dimensions of my own ignorance.

“It didn’t solve my ignorance. It didn’t solve all of our problems. But it changed my life. And now our story is legend to the children who followed.”

Well, yeah. Especially that tunnel. That needs to be right up there at the top of Dallas legends. The Three Man Tunnel tells us everything we ought to be getting from our regular batterings, but the batterings are too … you know … just too battering sometimes. Lights Out is terribly sad, wonderfully happy and hugely revealing. Go here.