It all started with a rash.

It didn’t itch. It didn’t burn. But the red splotches that appeared this past May on the hands and feet of Steve, a lifelong Dallas resident, were enough to cause concern. He’d had eczema before and knew this rash was different, so he scheduled an appointment at the Nelson-Tebedo sexual health clinic on Cedar Springs Road.

The clinic identifies itself as a “stigma free” healthcare space, and Steve, who is a proud gay man who’d hoped to handle his rash with discretion, felt comfortable there. He felt comfortable a few days after his initial appointment when he was told that, yes, he had tested positive for the sexually transmitted infection syphilis. And he felt comfortable with the doctor’s plan to treat the stage-two infection with several rounds of antibiotics.

“I had gotten my first round of antibiotics, and the director and nurse from Nelson-Tebedo said, ‘OK, so protocol is that you may or may not receive correspondence from the Dallas County Health Department,’” Steve, who requested his last name be omitted from this story, told the Observer. “He said that they work with each other and they just needed to tell [the county] that, yes, [I was] being treated at the facility. And so he goes, ‘So don't worry about answering any of the correspondence that may come to you via mail, text or phone calls.’”

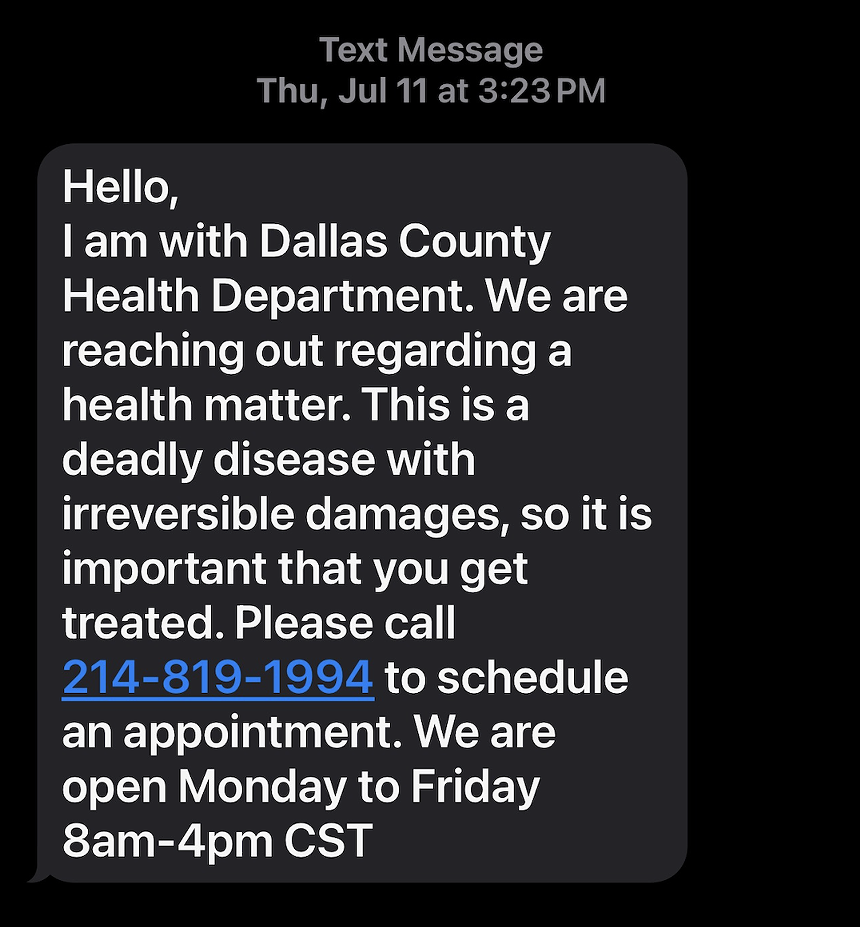

A few days later, Steve did get a letter from the county in the mail. He says that at his next appointment, he was once again advised to ignore it. Then, on July 11, Steve received a phone call and a text message at the same time. It was the middle of the workday and his phone was off, so the messages instead went to an iPad belonging to his elderly mother, which was linked to Steve’s phone number. While the voicemail that was left stated a nearly identical message to the letter he’d received — a quick request to call the county back to discuss a health matter — the text message was different.

“Hello, I am with the Dallas County Health Department,” a message shared with the Observer reads. “We are reaching out regarding a health matter. This is a deadly disease with irreversible damages, so it is important that you get treated.”

Steve’s mother saw the message as it came in on her iPad.

“Ten minutes [after the text message] my mom calls me. She's frantic. She was already crying. I thought that she had just completely lost it,” Steve said. “She goes, ‘I just received a text from the Dallas County Health Department stating that you have an irreversible disease.’ And right there it clicked.”

Just a few weeks earlier, Steve’s mother had undergone triple heart bypass surgery. The knowledge that her son had been diagnosed with a “deadly disease” skyrocketed her blood pressure into stroke territory, and Steve had to take her back to the hospital to be treated.

“I think [the employees of the Dallas County Health Department] think that they are on a silver pedestal, where they have the right to tell anybody anything because they are in a department that handles important information such as this.” — Steve, Dallas resident

tweet this

While at the hospital, she accused him of infecting her with a disease, and he was forced to divulge his diagnosis with her and with her doctors. Since then, other family members have learned about his condition and confronted him about it. And for several weeks, his mother avoided speaking to him.

Steve describes the experience as humiliating and a position he should have never been put in.

After reaching out to the Dallas County Health Department, he says he was told they agreed. He also says he was told the employee who texted him went off script in an attempt to get a response.

“We are aware of the situation and have taken some of the appropriate remedial steps regarding it, and are in the process of addressing this incident with the patient,” Philip Huang, director of the Dallas County Health and Human Services Department, told the Observer.

Keeping Tabs on an Infectious Disease

Steve initially chose to get tested and treated at Nelson-Tebedo in order to keep his diagnosis private. According to a statement provided to the Observer by Paul Miller, director of prevention services at the clinic, syphilis tests performed by Nelson-Tebedo are tested by the Dallas County lab, and the clinic is required by law to report positive cases of certain diseases including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia and hepatitis C.

Once a positive result is reported to the county, the clinic also includes information about whether the patient has been treated already. In Steve’s case, his ongoing treatment and guidance from doctors led him to believe he did not need to respond to the county’s correspondence.

“You've probably heard of contact tracing; it became very popular during COVID. It's something that we at public health do all the time with various conditions like STIs, tuberculosis and other communicable diseases,” Huang said. “So, [messaging a patient] is part of that process. This is [an illness where] we try to reach out to people and identify contacts, things like that.”

Huang added that the communication process is supposed to be gradual, starting with letters and moving on to staggered phone calls and text messages.

According to federal laws outlined in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), patients have a right to their medical information being kept private. Guidance on the Texas Health and Human Services website advises that medical professionals must “protect the privacy of private health information and limit the use and disclosure of that information” during in-person and electronic communications.

“My rights were violated. I know that for a fact,” Steve said. “I think [the employees of the Dallas County Health Department] think that they are on a silver pedestal, where they have the right to tell anybody anything because they are in a department that handles important information such as this.”

While Huang was not able to say what steps have been taken to deal with Steve's case, he did say that employees are trained on what is, and isn't, appropriate to say when communicating with a patient.

More than anything, Steve wants an apology. He can't talk about the ordeal, or the impact it had on his mother's health, without getting emotional. And he wants to ensure no one else has to go through what he did.