The post went on: “My question is how do we organize and improve poverty-stricken working class neighborhoods and schools without the negative effects that gentrification brings? How do we gentrify an area while keeping it demographically diverse financially and culturally?”

That may be a good question. I’m not sure. I guess it assumes that, without some kind of control or mitigating influence, gentrification reduces financial and cultural diversity. I’m stumbling just a little on that point, because, at least at first, gentrification obviously increases diversity.

But, wait. What is it? My favorite website for figuring out urban puzzles is Strong Towns. They say the meaning of the word, gentrification, can be all over the map, depending on who’s using it, but they point out two things that seem useful.

In English language terms, gentrification is a relatively new word, coined in the 1960s. And when it was invented, it had specific reference to poor people getting pushed out by richer people:

“When it was first coined by British sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964, ‘gentrification’ was intended to refer specifically to residential displacement like the kind experienced by poor workers in urban London neighborhoods as the middle class (or the ‘landed gentry’) moved in.”I was glad to find that explanation, because, otherwise, the term always stuck in my throat. I live in what is supposed to be a gentrified part of Dallas, Old East Dallas. I think the world of most of my neighbors, but when I scan around the ’hood, I never see a whole lot of people I would call gentry. So now I know. It’s a British-ism, so it’s not supposed to make perfect sense.

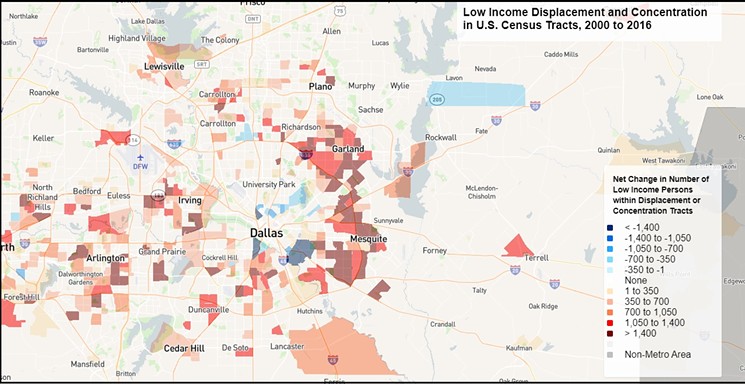

I say my neighborhood is gentrified, but not all the serious studies of this sort of thing agree. It may be that Old East Dallas has already pushed out so many of its poor people that it doesn’t qualify as gentrifying anymore. A 2015 study by Governing magazine lists my area as a “tract not eligible to gentrify.”

The same study shows major gentrification between 2000 and 2015 in the South Dallas/Fair Park area, touching on a phenomenon I have reported here before. Last August I wrote that South Dallas near Fair Park is the site of the city’s fastest-growing property values. Some people familiar with the area told me they think those increases are being driven by working class Mexican immigrant families, some of them undocumented, buying houses formerly held by absentee landlords and occupied by non-rent-paying squatters.

All of that is a little hard to quantify, but it is supported by a drive-through and the evidence of one’s eyes. Where homeless street people once staggered the sidewalks, now scowling mothers take their children by the hand and walk them to school. It does feel safer. I’d rather get into it any day with a stoned panhandler than take on one of those mothers."(H)ow do we organize and improve poverty-stricken working class neighborhoods and schools without the negative effects that gentrification brings?" — Reform Dallas Facebook post

tweet this

So is that gentrification? Is diversity being sacrificed there? Surely, people are being displaced. I’ve never heard anyone even speculate where the homeless people go when they get pushed out of South Dallas. All I know is that every 90 days, the city sends out bulldozers and scrapes them out of their camps. Is that gentrification? Or just scraping?

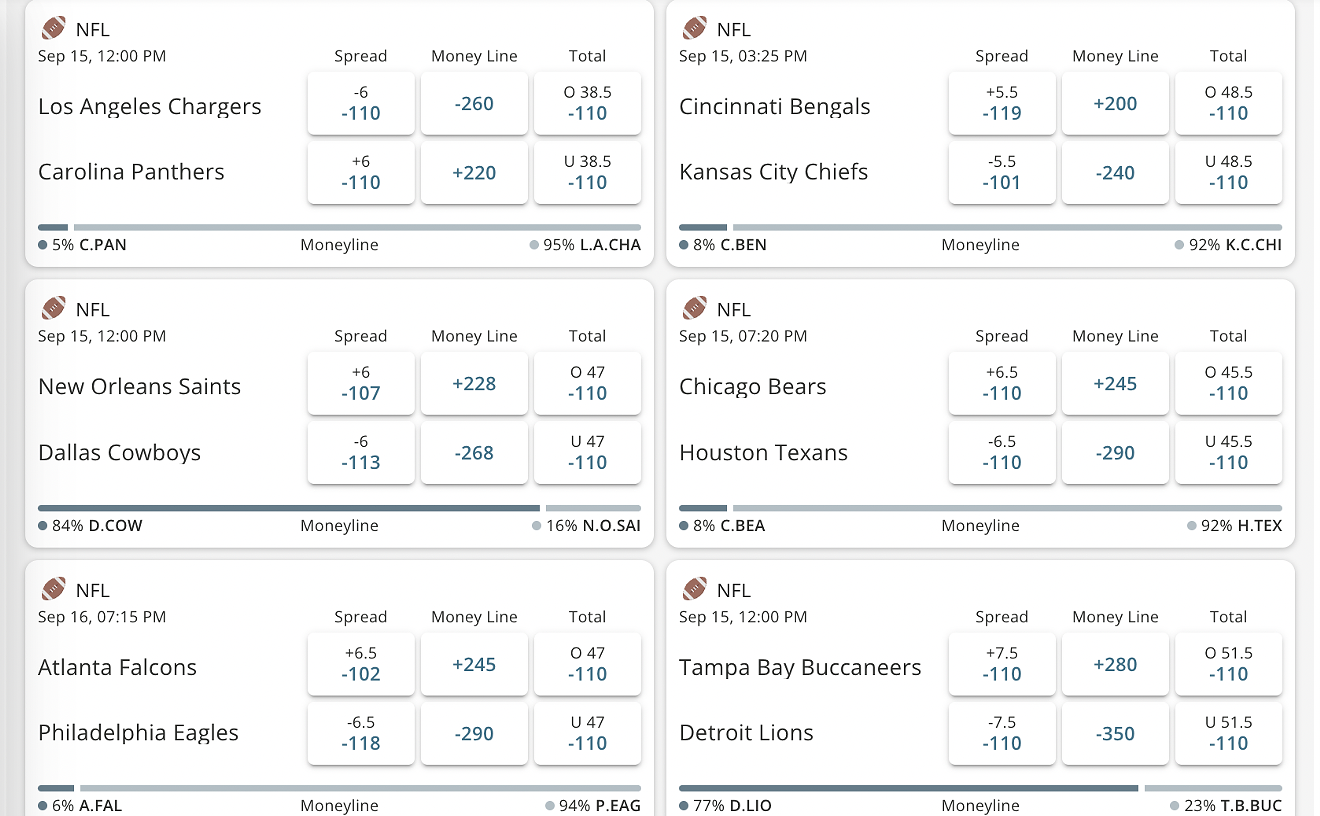

If we go up to 10,000 feet and look back down, the larger pattern comes clear. The entire city is being gentrified, and that means educated people with money are coming into the center city and poor people are going out to the suburbs, no doubt about it.

At the end of 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas published a study showing that since 2000 the population of college graduates and median income persons has surged in the state’s major cities. The farther out you move from the downtowns of Texas cities, the more the growth diminishes at the high end.

In ethnic terms, we are taking about non-Hispanic whites abandoning the suburbs for the urban core. An exception to this trend are Asians, who seem to be more evenly distributed between downtown and the boondocks.

According to the study, between 2000 and 2015, income growth in Dallas within the three-mile ring of downtown was twice what it was three to five miles out, five times what it was five to 10 miles out.

Pink, orange and brown denote rising concentrations of poverty between 2000 and 2016. Blue and gray show poor people moving out.

Institute of Metropolitan Opportunity

But why would the other cities see more construction in the outer rings if the people with the money are coming into town? It may be the harbinger of a net population shift — population increasing in number but diminishing in wealth in the suburbs, while the opposite happens in the city.

If that’s what it is, what does that augur for non-affluent people who still live inside the inner ring? Last July, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia published a study that took a direct dive into that question. The authors tried to find out how many people get shoved out, where they go and what effect it has on their lives.Those poor and less educated families who manage to stick it out and stay in a gentrifying area reap certain benefits. The area gets safer. The schools get better. The shopping improves.

tweet this

One of the findings was that 30% of less educated renters and 60% of less educated homeowners stay where they are even after the gentry move in. The study found that gentrification increases the out-migration of the original population by 4 to 6 percentage points, but that’s against a background of high transience even without gentrification.

Before the gentry ever began moving in, 70% to 80% of renters and 40% of homeowners were moving somewhere else anyway. The study found no evidence that less educated people and people with lower incomes who depart from gentrified areas wind up moving to poorer more dysfunctional places. Most of them move to places like the ones they were in before.

Meanwhile, those poor and less educated families who manage to stick it out and stay in a gentrifying area reap certain benefits. The area gets safer. The schools get better. The shopping improves.

The study was a little light on what happens to poor families when property values start soaring and their taxes go up. The authors suggest that the financial pain of higher property taxes is offset by the new wealth that home-owning families of modest means are able to achieve by holding onto a house in a place where values are rising.

I guess that’s the trick — holding on. I certainly have had families in West Dallas tell me that the houses they bought from former low-income landlord Khraish Khraish just a few years ago already have created more wealth for them than they could ever have saved from wages. But they’re the ones who somehow got their taxes paid and held on.

Some of the outcry against gentrification in southern Dallas rings hollow for me. I think an older entrenched political class there fears it will not be able to hold onto power when the voting base gets more diverse. I suspect they’re right. I don’t begrudge anybody his survival instinct, but, then again, it’s hard to see a lot of hope for change and progress in that mentality.

We’re also up against the historical fact that there never has been much real appetite for assimilation in ultra-conservative, church-centered, black southern Dallas. How ironic will it be if the traditional southern Dallas black community emerges in the years ahead as the city’s last bulwark and defender of racial segregation? Maybe in the weeks ahead.

But that 10,000-foot picture is clear. The action is coming to town. Everybody wants in (except the Asians). Here comes the money, but also — remember South Dallas/Fair Park — here comes a working class that wants viable schools and neighborhoods.

The question raised on Reform Dallas — man, that’s a weird website — is a good one. In this burst of vitality and energy and creativity coming our direction, is there some way for it all to resolve itself without just transferring the monochromatic, insular life of suburban subdivisions to the inner city? I bet there is, because … young people. They don’t go for monochromatic.

Hey, to be fair to the suburbs, they’re way more diverse than they used to be. Some of them are more diverse than my inner city neighborhood, probably reflecting a lot of generational change there as well.

People only come in and try to push other people out because they’re nervous living near people who don’t look like their cousins. That’s my generation, not young people. I would guess that younger people coming into the city are going to find ways to mix and match where everybody gets something out of it and hardly anybody has to get totally screwed.

Hardly. I haven’t heard any answers for the drug-addicted transients getting pushed out of South Dallas. In fact, I haven’t even heard the question.

The big picture is clearly of better times ahead, more vitality, more diversity, more of that social sizzle that makes living in a place fun. But not without some sobering responsibilities.