Randle has been on her own since leaving foster care. "I don’t have any parents to teach me how to do this or do that or how to budget or anything like that,” Randle says with an almost sweet lilt in her voice.

Throughout her teens, she worked at fast-food restaurants. Then, at 19 she was directed to a nonprofit program, the We Are One Project, which was created by a local businessman for young people just like her. The mentorship program aimed to fill some of the voids, the missed life lessons — both big and small — and offer help with housing, therapy and budgeting.

Several years later, the We Are One Project has blossomed into a robust opportunity for former foster kids that still offers crucial mentoring as well as career help and a job. And it all happens in a coffee shop, La La Land Kind Cafe.

It's also how Randle got her car back.

••••

Francois Reihani, 27, is sitting in the middle of a La La Land Kind Cafe just off Lower Greenville Avenue — the coffee shop he founded and is the CEO of — recalling how he got to this point. He’s tall but folds up comfortably on a beige couch, talking quickly but at ease. The coffee house has bright yellow and white accents. With the midday sun pouring through the windows, it emanates a pleasant glow.

There’s usually a line of customers from the register to the door here: women in Lululemon athleisure wear buying tan drinks topped with white clouds. There are no obvious signs the coffee shop is on a mission to help young people pushed out of foster care at 18.

A meeting started him down a path that led to the cafe and the We Are One Project. In 2017 he’d opened Pōk in the West Village while still a student at SMU. The restaurant served bowls of sushi-like diced raw fish, originally popularized in Hawaii, and it did very well as one the first of its kind in Dallas. But he soon realized that he wasn’t going to be happy with that life for long. The success didn’t make him feel any better. He wanted to be able to look back on his life in his old age and have something besides money to show for it.

“So, I wanted to figure it out,” he says.

A friend, Erin Jesberger, invited him to a meeting held by the nonprofit CASA, or Court Appointed Special Advocates. The Dallas chapter of CASA, established in 1979, uses volunteers to act as a voice, appointed by judges, that "protects children and restores childhoods." Last year, 1,500 volunteers served more than 3,000 children in Dallas County. Topics at its monthly meetings vary, and the focus for the one Reihani attended was about what happens after foster youth age out of the system on the day they turn 18.

"The first kid got up there and started going through his life story," Reihani says. He talked about being taken away from his parents at a young age and going through 15 different homes, and how most of the foster parents were just in it for the money.

When a home didn’t work out, the young man had to go to foster care centers that were no better than the many homes he had lived in. He described a litany of dire situations.

“Then at 18, literally on that day, they kick you out of the house,” Reihani says. “And what got me was if you’re out on the street at 18, you’re the easiest target in history for either getting thrown into drug rings or prostitution. The craziest stat I ever heard was that over half of all the homeless population has been in foster care.”

Several organizations cite this statistic, but pinning down the number is difficult. In Texas, 1,277 aged out last year according to state data, and on average receive six different placements. The Simmons Foundation found that female foster youth are almost five times more likely to become pregnant compared to other Texas teens. And according to the Texas Education Agency, 62.6% of students in foster care graduate from high school, compared to 90% of all other students.

There were three speakers at that CASA meeting, all formerly in the foster care system. The first account was painful to hear; the next two were no better. “It kept getting worse,” Reihani says.

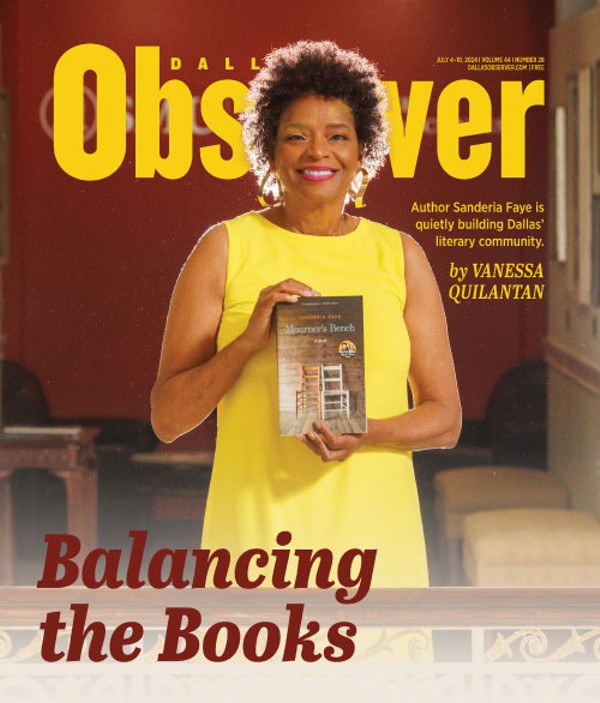

The first La La Land Kind Cafe opened just off Lower Greenville Avenue but has since expanded as far as California.

Kathy Tran

Then Reihani examined the life of CPS workers. He found that many choose the career because they want to make a change in the lives of young people but they end up getting swamped with case files and become drained because they can’t make any real change. “And they’re getting paid shit,” he adds.

According to the state's Family and Protective Services database, the average yearly salary in Dallas County for CPS caseworkers is just over $53,000. In 2021, the turnover rate for CPS investigations workers was a stunning 41%, up from 27% in 2020.

“The more you go into it, the more you realize it's a deep dark hole. So much fucked-up shit going on, it doesn’t make sense. And so I’m thinking, how is this happening? How the fuck is this happening in America?”

In Texas, foster youths are “emancipated” or “aged out" on their 18th birthday. Texas offers some transitional living services for foster kids until they are 25 years old. Money is available for living expenses and even free college tuition through the state college tuition waiver. But many kids don’t know about the programs, and navigating the paperwork is a challenge.

A Texas State University study found that about 3,000 foster youths use the tuition waivers each year, or about 10% of the total number of young adults it’s available to.

Sarah Worthington is the director of Texas Foster Youth Justice Project, a nonprofit that helps current and former foster kids understand their legal rights. The group also helps sort out basic paperwork to allow young people to get started in life.

“One very common challenge for youths who aged out of foster care face involves their identification documents,” Worthington says. “Texas law requires that all youths aging out of care have their birth certificate, Social Security card and Texas ID or driver’s license, but many either don’t have these documents when they exit care or they lose them and have massive difficulties replacing them. Without ID, they are unable to access safe and stable employment. Similarly, many young adults also struggle to obtain safe housing, which makes it difficult to get and keep a job.”

Free college could seemingly solve many problems, but Worthington points out that it comes down to a hierarchy of needs, “If they have somewhere to live, if they have a job, yeah, they can go to school, but if those needs aren’t met, they’re much less likely to utilize the tuition waiver."

Seeing the hurdles in the path out of foster care inspired Reihani to create the We Are One Project as a “tool for businesses to come together to employ foster youth,” he says. The initial focus was on therapy, housing, education and mentorship. But what he found was that these young adults couldn’t get and keep a good job.

“When we first launched, it was a tornado. I thought we were going to come in and solve a problem pretty simply and that just wasn’t the reality. I’m a delusional person,” Reihani says with a laugh. “It was only Band-Aids.”

So, Reihani created La La Land Kind Cafe to provide former foster kids with jobs.

He landed on the coffee shop concept because it’s typically an easy-going, communal environment. Plus the job isn’t too difficult and has no significant barriers to entry. After being interviewed and hired, interns start out making $10 an hour, with a focus on learning how to help run a busy coffee shop and to become part of an organization. At the same time, the interns receive other services as needed through the We Are One Project, which is funded by the coffee shop.

Jesberger, the CASA advocate who invited Reihani to that initial meeting, says they’re also learning important lessons that they may not have learned at home.

“That’s where he [Reihani] comes in and does that training. It’s such a gift,” she says. “He says, ‘On time is late,’ stuff a normal parent would probably teach a child, but they weren’t born into that so they don’t know that your clothes are expected to be clean and under your fingernails needs to be clean when you’re working with food.”

The first La La Land Kind Cafe opened off Lower Greenville Avenue in 2019. Reihani hired 10 former foster youths to work in the cafe but quickly realized that was bad for both store operations and the employees. It didn’t allow for enough individual focus.

“We had to really hone in on the training. We couldn’t expect them to come in, train for a day, then start the job,” Reihani says.

Over several years the operation has gone through many tweaks. Now there's an eight-week program designed to train just two former foster youths at a time. (Not every person working at a La La Land Kind Cafe was previously in the foster care system. Most weren’t.)

The eight-week program allows new workers to focus on learning the job and social dynamics. Most then continue on with jobs at any of the La La Land Kind Cafe locations, but there’s also an option to find work elsewhere.

“They can tell a director, ‘I want to work with dogs,’ and so the director will help them find a job that they’re passionate about,” Reihani says.

Kadee Randle was one of the first foster kids to be part of the We Are One Project. She then went on to become one of the first baristas when the cafe opened.

“I didn’t have much money, so they would go out of their way to help me with a deposit for my first apartment,” she says. And when her car was towed recently, they helped her out then too. “They did me a big favor and helped me pay my car note, so I was fresh and could start over. That was pretty cool.”“There wasn’t someone we could go to and say, ‘Hey, let’s look at how they do it.' And that was the point: We wanted to build a program so that when other businesses come to us we can show them how to do it.” - Francios Reihani, founder and CEO of La La Land Kind Cafe

tweet this

Kathleen LaValle, the president and CEO of Dallas CASA, says programs like La La Land are vital for young adults aged out of the system because the programs provide not just employment, but guidance and structure. Part of the mentorship includes weekly check-ins with directors and help with budgeting.

“Many young people who exit the child welfare system are understandably anxious for independence,” LaValle says. “Yet, they face so many heightened risks, including incarceration, substance abuse, homelessness, food insecurity, unemployment and even sex-trafficking victimization.”

What La La Land’s program provides, La Valle says, is a sense of community and security while navigating the transition to a healthy and independent lifestyle.

“While the expectation is that each team member will become a responsible employee, this all happens in a supportive environment where they feel they belong and are valued,” La Valle adds.

••••

Aaron James of Los Angeles entered the foster care system when he was 5 years old. He was in the system for a couple of years before his grandmother was able to take him in. James, now 22, attends West Los Angeles College, where a school counselor recently connected him with the director at a new La La Land Kind Cafe in Santa Monica, the first location outside Texas. He was accepted into its internship program about five months ago.

Now he goes to school, studying for a theater arts degree while working at La La Land. His immediate goal is to transfer out of community college to a four-year school.

The environment at La La Land was something he couldn’t give up after the internship, James says. “I had to stay. I love everyone, and the training and the managers are so amazing.”

That's something else to know about this cafe and the culture created there: They love love. In addition to creating the mentorship program, Reihani has created a coffee shop that is fueled by kindness. Baristas pass out as many “love yous” as they do coffee beans. Black hats for sale on the shelves at the stores are stitched with "Don't be a Dick." The La La Land official motto is "normalize kindness."

“At Starbucks [where James previously worked] we’d get a lot of angry customers and it was our job to make them happy with a thank you. But at La La Land we tell them ‘Oh, we love you, have a beautiful day,’ and it makes them happier,” James says. “I love the kindness motto. It’s one of my favorite things. It’s a happier environment.”

In Dallas, Randle, who works at the Oak Lawn location, says Reihani is like a brother to her now — tough love and all.

“When I was late to work all the time or calling in, it was him saying, ‘That’s not allowed, you can’t do that.’ I didn’t know, I thought all these people love me, they’re not going to fire me,” Randle says with a light laugh.

“He was like, ‘I have to teach you a lesson, you’re gonna take a break and stuff,’” she says. “A lot of stuff doesn’t happen the way I want it to happen, but he’s helped me with learning how to manage my money.”

When asked about the biggest lesson Reihani has imparted to her she says, “Go the long way. Just by being kind, a lot of positive things will happen. Even if other people aren’t kind. They’ve just been a really big support system in my life for the last four years.”

For Reihani, a primary goal in all of this is to create a playbook for other businesses to use to provide a business structure everyone can use.

“There wasn’t someone we could go to and say, ‘Hey, let’s look at how they do it,’” he says. “And that was the point: We wanted to build a program so that when other businesses come to us we can show them how to do it.”

In terms of sharing this program with other businesses, the largest retailer in America is in. “We worked with Walmart to launch a program, and are still fine-tuning to be able to fully launch this with others in the near future,” Reihani says.

••••

Patrick Murphy is the general manager at the store where Randle works. We meet there one day to talk. Billie Eilish’s “My Future” is playing in the background, the music a bit louder than normal. Eilish’s voice takes a delicate turn: “I love my future and you don’t know her.”

The coffee shop is packed, again. Not an empty seat. The line down the counter occasionally reaches the door as those waiting for coffee look for a seat.

“She [Randle] made the first drink ever at La La Land number one,” Murphy says with a big smile. “I’m proud of her for growing into being a mom, providing that life she didn’t get.”

Murphy talks about the “normalize kindness” motto and the impact it’s had on his life too.

“A lot of them [in the mentorship program] haven’t received that growing up or in a work environment, so they get that experience here,” he says. “It’s changed me as a person. I didn’t realize how many times I needed to hear ‘I love you’ in one day.”

Randle hopes to start college after she completes her GED, and at some point, she wants to become a general manager at La La Land. Her goal is to be a two-car family with her boyfriend, so they don't have to share a car, one working during the day and the other at night. In the next year or so, she also hopes to be able to afford daycare for her daughter while she pursues her career goals.

As for the future of La La Land and the mentorship programs, Reihani has expanded to Houston and Santa Monica, with more stores in the works locally. "My long-term goal is really endless," he says. "I want La La Land to be able to touch every human on the planet in some capacity."