“You’re a food writer,” they often write. “Stick to describing the food!”

But in Dallas, especially, it’s impossible to understand local food culture without also understanding a long history of political and racial conflict.

Segregation and discrimination are at the heart of how Dallas food got the way it is today.

Dozens of culinary questions can only be answered in Dallas by examining its politics and history. Why are so many of the black-owned restaurants located in South Dallas, Hispanic-owned restaurants in Oak Cliff and Asian-owned restaurants in suburbs? Who gets to open new restaurants in trendy locations, and who doesn’t? How did Uptown and Deep Ellum become the neighborhoods they are today? Why don’t more restaurants have black executive chefs? Why have professional critics reviewed so few restaurants south of Interstate 30? Why did they build a “restaurant theme park” at Trinity Groves? What meats would you put on your ideal barbecue platter?

The restaurant business is just part of a city’s economic system, and Dallas’ system is fundamentally biased. Consider the Urban Institute’s 2018 survey of economic inclusivity in American cities, which measured how equitably a city’s economy includes its poorer and historically oppressed populations. The Institute ranked Dallas dead-last out of 274 cities, behind rivals such as Shreveport and Detroit.

In part, this is because Dallas’ leaders spent the past century pushing black people and immigrants out of their neighborhoods and building new northern suburbs for white people. Deep Ellum was an original freedman’s town, a history that at least one bar in the neighborhood has acknowledged in recent days in its social media posts.

Another freedman’s town was dissolved and razed to build Uptown, a process carried out with the help of government authorities, who built an expressway mere feet away from African Americans’ historic cemetery. In a cruel irony, Uptown now houses many of Dallas’ stereotypical “$30,000 millionaires.”

In 1953, white Dallas struck again, razing more black homes for an expansion of Love Field. Even more callously, a historically black community called Little Egypt was destroyed to make way for a strip mall.

The construction of Dallas’ neighborhoods, and thus the food scenes in each of those neighborhoods, is rooted in our city’s history of white people deciding they want to live somewhere, or even have a shopping center there, and kicking all the non-white people out.

This is still happening. In recent years, a group of wealthy white people noticed a patch of land very near downtown Dallas that could, perhaps, be profitably razed and rebuilt as luxury apartments for upper-class professionals. So they designed and built a restaurant theme park in West Dallas called Trinity Groves to act as a spearhead for their development. It worked.

The connection between gentrification and food has not always been as explicit as it is in Trinity Groves. But the connection between food and politics is ever-present in our city. A 2015 Pew study found Dallas to be one of the most racially segregated cities in the United States, and a separate survey conducted in 2018 agreed.

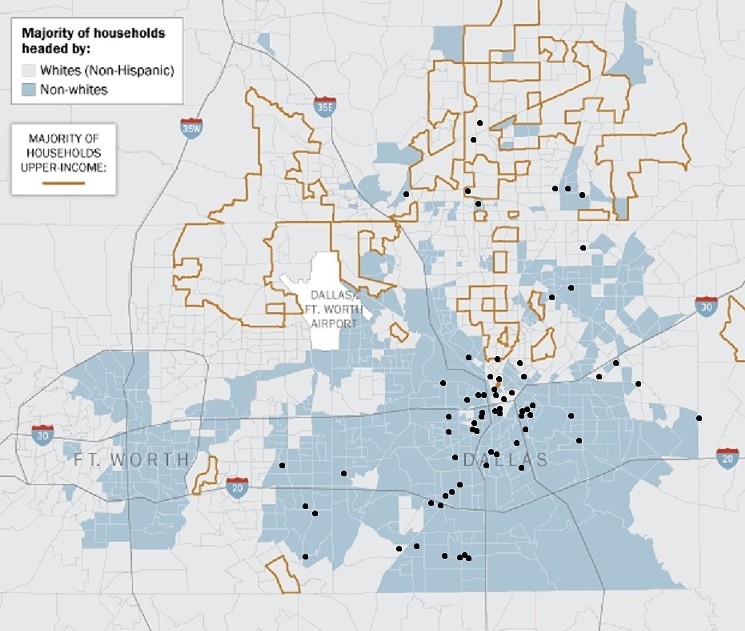

Below I’ve taken a map from the 2015 Pew study, showing which parts of Dallas are majority-white and which are majority non-white. I’ve added dots to the map: Each dot represents a black-owned brick-and-mortar restaurant, as listed in a guide published by Deah Berry Mitchell and Dalila Thomas at Soul of DFW, then added another dozen or so businesses that are not on their list.

Black-owned restaurants in Dallas plotted against a map of the city's racial and economic divide

Pew Research / Brian Reinhart

Former freedman’s district Uptown now has just one black-owned restaurant in this data set, run by a former NFL player De’Vante Harris. In a new interview with D Magazine, chef Troy Gardner — who operates V-Eats in Trinity Groves — said he lost an opportunity to open a restaurant in Uptown when a prejudiced partner disrupted the deal.

Of the unnamed partner who scuttled his Uptown kitchen, Gardner said, “I have no doubt that the reason that deal fell through, because I was told by multiple people, was that he wasn’t a game player when it came to minority businesses.”

Deep Ellum’s present landscape is similar. The neighborhood got its name from black people, but has just one dot on our business map: Omar Yeefoon’s perfect bar Shoals Sound & Service. Another recent arrival, Bottled Blonde, sparked controversy for publishing a dress code that appeared to be written as a license to discriminate against black customers.

Two cheeseburgers at Shoals in Deep Ellum for $14: The best food comes in a red plastic basket.

Nick Rallo

Dallas’ stark geographical divides between wealthy and poor and between black and white influence food in other ways, too. When delivery service Favor arrived in town in 2017, it announced a delivery zone that conspicuously omitted South Dallas. Controversy ensued. A decade earlier, a University of Texas at Dallas study of grocery locations showed that white Dallasites have far greater variety of neighborhood groceries.

Unfortunately, you can also see a northerly tendency in my own Top 100 Restaurants list, as published by the Observer. I believe my list is the most diverse list any local media source has produced, but that is a hollow compliment, and a sign that more progress must be made.

Dallas’ food media coverage has historically favored restaurants in wealthier, whiter neighborhoods. There are good and bad reasons for that. Among the good reasons: The underlying unfairness of our business landscape produces unequal dining scenes, national chains predominate in some poorer neighborhoods and most readers of food writing come from a class that can afford to spend more disposable income on eating out.

Among the bad reasons: Most of our food writers are white, many are incurious and some historically believed that certain foods and cultures were more deserving of attention than others.

To create a more equitable restaurant scene, Dallas needs action from everybody involved.

The media need to hire black and brown voices, or to share the spotlight if minority voices choose to start their own new media platforms. The white figures who predominate now should spend more time respectfully and sensitively sharing black and brown stories. (A role model for white writers is Daniel Vaughn’s tireless fight at Texas Monthly to steer barbecue lovers’ attention back to the cuisine’s African American roots.)

I’m on the hook, too, as the map above shows. This article will not stand alone; it will need to be followed up by more in-depth research, interviews, stories, history and analysis. Expanding review coverage in southern Dallas, DeSoto and Duncanville was my top priority for 2020 before the coronavirus destroyed the review schedule. The pandemic just means I have to get more creative.

White chefs, owners and culinary leaders need to ask themselves what it is about the environments in their kitchens that cause so many of our talented black cooks to prefer catering and private-chef careers.

Venue owners should investigate managers accused of deliberately discouraging black crowds. Landlords, developers and investors need to ask themselves why most of the business plans they like best happen to be created by white people. Maybe ask Monte Anderson, who runs a DeSoto incubator for black-owned businesses.

But the real change to Dallas’ food scene needs to come from citywide social and political action. Yes, food writers must purge their prejudices, business leaders must stop discriminating and diners must understand the deeper issues at hand, but all that’s peanuts compared with a systematic dismantling of our city’s racial and economic segregation. It’s peanuts compared to bringing about genuinely equal opportunities for white and black residents. It’s peanuts compared to battling gentrification and promoting inclusive growth.

In other words: Yes, go grab some spectacular food from a black-owned restaurant. But don’t stop supporting that business once you’re full from its lunch. Demand changes from our city’s leaders. Join debates online. Talk to your friends. Vote in every election. Donate to rights groups. March if you need to. Protest injustice. Understand that the cracks and bumps that show in our restaurant landscape come from a much deeper fault line.

If you’re a food lover in Dallas, you can’t just stick to the food.